The year 2024 marked the 600th anniversary of the birth of the merchant and diplomat Anselm Adornes (1424-1483). Published to mark the occasion, the volume of essays under review here concerns the Genoese-Bruges Adornes family – of which Anselm was the most influential scion – and the ways in which it succeeded in tying its history to the family’s devotion to the Holy Land, which became the core of a lasting legacy. The most visible testimony of this is the Jerusalem Chapel, a replica of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, and to this day one of the most original buildings in the city of Bruges.

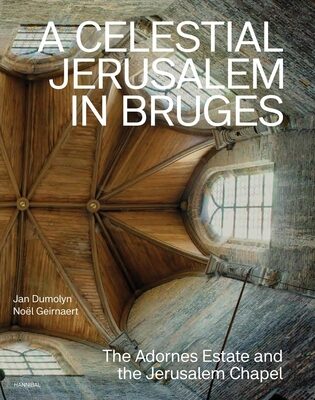

This generously illustrated book, edited by Jan Dumolyn and by Noël Geirnaert (to whom we owe several of the foundational publications about the Adornes and their family archive), is just over 300 pages long. The first half consists of essays by scholars from various disciplines, including medieval history, art and architectural history, archaeology, and bioanthropology. The latter half of the book is reserved for photographs that are referenced as illustrations in the essays, and a bibliography. There are also three appendices, most notably a full transcription by Geirnaert of the now famous testament that Anselm Adornes made upon his departure for the Holy Land in 1470. It mentions two paintings of Saint Francis by the hand of Jan van Eyck – generally agreed to be identical to paintings today in Turin and Philadelphia – that Anselm bequeathed to two of his daughters, both nuns. In addition, the volume includes useful plans of the larger estate of which the Jerusalem Chapel is part; maps of the Adornes family’s fiefs and seignories in Flanders and Scotland (the latter a legacy of Anselm’s dealings with the Scottish king James III); and a family tree that extends to the present-day heirs and stewards of the Adornes Estate.

In the introduction, the editors set out the relevance of the Jerusalem Chapel by situating it within the strategy employed by members of the Adornes family to establish themselves in Bruges as expatriates from Genoa. In the first of the seven essays that follow, Jan Dumolyn and Mathijs Speecke clarify the family’s background. Archival evidence newly unearthed by Speecke has revealed the earliest known mention of the family in Bruges: a poorter of the city named Pieter Adornes, a man of considerable wealth from Genoa, documented in 1327. Thus, the family’s Genoese origins and presence in Bruges by the early fourteenth century have been further confirmed. The story of its founding father Opicius Adornes, said to have been a crusader and part of the retinue of Guy Dampierre, the Count of Flanders, on his pilgrimage to Palestina in 1269-70, can now be relegated as a purposefully constructed myth. That both family history and family mythology are at times difficult to untangle, let alone verify, is further demonstrated by Paul Trio’s contribution. Trio shows how painstaking critical historical analysis is necessary when examining the oldest surviving genealogy of the Adornes family, which dates from the early sixteenth century but was probably based on earlier notes and recollections (and written down for specific reasons).

The contribution that follows, by Nadine Mai, based on her 2021 book on the Jerusalem Chapel, moves away from the family’s history to its tangible legacy. Mai provides a concise, illuminating account of the Jerusalem Chapel – founded shortly before 1429 by Pieter II, the father of Anselm (from whom he probably inherited the Saint Francis paintings) and by Jacob Adornes, Anselm’s uncle – as part of an ensemble of fifteenth-century buildings that comprise the Adornes Estate: the city palace built by Pieter II, the house of Anselm and his wife Margareta van der Banck, the garden, and the almshouses. Mai stresses that the site was multi-purpose: the users of the Chapel extended beyond the Adornes family to include not only the twelve poor widows living in the almshouses but also the larger urban community, which early on included the guild of glovers and later, from the first quarter of the sixteenth century onwards, the Jerusalem Brotherhood of pilgrims. It is these overlapping functions and parallel spheres – religious, philanthropic, public, private – that make the Adornes such a fascinating example of the late medieval elite. Brigitte Beernaert’s informative contribution continues with a focus on the physical dimension of the Adornes heritage by providing a broad view of the spatial context of the Adornes Estate as well as of other properties held by the family, seen within the urban fabric and contemporary development of Bruges, followed by a precise account of the individual buildings that make up the Estate.

By drawing on the inventories of the Jerusalem Chapel, Jos Koldeweij’s essay for the first time provides an overview of its furnishings (including relics brought from the Holy Land by Anselm and his son Jan, who accompanied him; they were the first ones to travel to Jerusalem, even if the family propagated a much older connection to the city) and, by extension, more specific insights into the use of the Chapel. Koldeweij suggests an embroidered cloth in the earliest surviving inventory of 16 May 1521 could have been used to cover the center panel of Jan Provoost’s altarpiece – although itself absent from any of the inventories – in the upper chapel during Lent. Unfortunately, only the central Crucifixion panel of this triptych (now housed in the Groeningemuseum, Bruges) is illustrated in the book, without its wing panels devoted to Saint Catherine (now Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, and Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp). The altar of the upper chapel, or Chapel of the Cross, was dedicated to Saint Catherine, who was of great importance to the Adornes family, as evidenced by the stop Anselm and his companions made on their way to Jerusalem at Saint Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai, and by the frequent appearance of Catherine’s wheel (along with the Jerusalem Cross) throughout the Chapel. As an aside, it remains little known that Provoost’s Crucifixion is actually owned by the church of St. Nicholas in Koolkerke, some 4 km northeast of the Jerusalem Chapel; it functioned there as an epitaph to François Cortals (d. 1786), procurer and notary of the Franc of Bruges (Brugse Vrije). Since 1971, the painting has been on loan to the Groeningemuseum.

That so many of the Jerusalem Chapel’s furnishings, which included paintings, sculpture, silver, and textiles, are not found on-site anymore is unsurprising, considering the particular liturgical functions and movable nature of most of these precious objects, in combination with the mechanism of inheritance – Anselm alone fathered sixteen children. Two of the largest and most monumental works that remain in the Chapel are the late fifteenth-century stone Calvary altarpiece and the funerary monuments of Anselm and his wife Margareta van der Banck, made by the stone mason Cornelis Tielman. The tombs are the subject of a short contribution by Femke Germonpré, Frederik Roelens, Guenevere Souffreau, and Katrien Van de Vijver. In 2021, when the tombs were temporarily removed for restoration, the two vaults underneath Margareta’s tomb were found to contain a skeleton of a female individual, in all probability Margareta herself (in a first archaeological study of the tombs in the 1980s, a coffin that probably once contained Anselm’s heart was retrieved). Additionally, remains that belonged to other persons of unknown origin were also present.

The legacy of the Adornes family is very much alive today. The engagement, care, and responsible stewardship of the Estate evident in the final contribution to the book by Véronique de Limburg Stirum – who has been its driving force since she and her husband Count Maximilien de Limburg Stirum, the seventeenth generation of the family, came to its helm – will ensure that in addition to its long past, the Adornes Estate has a bright future ahead. The book also anticipates this; building on earlier studies, it is an excellent addition to the literature on the Adornes, as it adds further insights and points future researchers in the direction of unexplored topics and materials. If one were to find a point of critique, more in-depth discussion of the works of art (including books) owned and commissioned by the Adornes would have been a nice addition, to highlight the family’s artistic tastes and patronage, and to include some of the artisans involved in these projects. In all, though, the book beautifully achieves its goal of instilling in the reader a profound admiration for a special place in the city of Bruges whose multifarious meanings and singular significance deserve to be thoroughly studied.

Anna Koopstra

Musea Brugge, Bruges