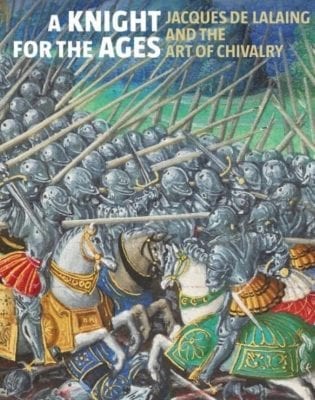

Jacques de Lalaing, the bon chevalier, a renowned jouster and military commander in the service of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, died in 1453, aged only thirty-two, at the siege of Poeke during the Ghent War. Some twenty years after his death, the Livre des faits de Jacques de Lalaing was commissioned to record his deeds. Only three fully illuminated manuscripts of the Livre des faits survive; the J. Paul Getty Museum purchased one of them, which includes a magnificent frontispiece by Simon Bening (c. 1483-1561), in 2016.

A Knight for the Ages, edited by Elizabeth Morrison, senior curator of manuscripts at the Getty, applies a cross-disciplinary approach to the analysis of this remarkable and, until now, little-studied manuscript. In Part One, Zrinka Stahuljak provides a plot summary, followed by her translations of the texts relating to each of the eighteen miniatures. The layout, with the manuscript text facing a near-full-page color reproduction of the relevant miniature, facilitates assessment of an image’s adherence to the text. Each image is accompanied by a small-scale reproduction of the original page, forming a useful reminder that the images were not designed to stand alone. Part Two consists of eight essays by Morrison, Stahuljak, and six other leading medievalists. The object itself is their starting point and serves as a constant reference for wider explorations.

Wim Blockmans places the manuscript in the context of Burgundian court culture, chivalric values, and Jacques’s life and family, proposing that two fellow members of the Order of the Golden Fleece, Adolph of Cleves, Lord of Ravenstein (1425-1492), and Anthony of Burgundy (c. 1428-1504), who were at Jacques’s side when he died (Plate 18) may even have sponsored the writing of Jacques’s biography. Rosalind Brown-Grant and Stahuljak situate the Livre des faits within the genre of chivalric biography and courtly romance, noting its hybridity of textual form such that it is “a chronicle but also a social commentary, a romance and a didactic text” (Stahuljak, p. 86). Anne-Marie Legaré lists and describes the thirteen surviving manuscripts, of which at least five belonged to the Lalaing family, and traces the provenance of the Getty manuscript through the branches of the Lalaing family, developing a convincing case for its most probable patron, Antoine de Lalaing, Count of Hoogstraten (c. 1480-1540). Hanno Wijsman analyses the Getty manuscript in relation to the two other fully illuminated copies (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. fr. 16830 and private collection of the Count of Lalaing) which all include eighteen illuminations of essentially the same subjects, placed at matching textual divisions. Margaret Scott and Tobias Capwell examine, respectively, the details of dress and armor which they demonstrate to be contemporary with the commission of the Getty manuscript. Close analysis, tested from these different perspectives, has produced results on date (c. 1530), likely patron (Blockmans and Legaré concur that it was Antoine de Lalaing), and the illuminator of seventeen of the miniatures (an artist in the circle of the Master of Charles V, named henceforth as the Master of the Getty Lalaing), who may well have trained as a panel painter (Morrison, p. 102). Helpful background is provided by a timeline and a Lalaing family tree.

The consistent theme across the essays is the inter-play of image and text, with detailed analysis revealing discrepancies and yielding numerous lines of enquiry. Wijsman notes that the Getty artist changed the iconography most strikingly from the preceding manuscripts in Plate 6 (Jacques kneeling before the King of Castile), transferring the scene outdoors and showing bull-baiting, thereby more faithfully reflecting the text. The reverse applied to the scenes of foot combat where some key details in the text – such as Jacques fighting with his visor open – were ignored, leading Capwell to conclude that the illuminator was working from instructions rather than reading the text directly. The Getty Lalaing raises the wider issue of copies and intermediary and iconographic influences, and the probable role of lost manuscripts (Wijsman posits that there were at least two). Small details prove informative: the arms of the Duke of Burgundy in the Getty Lalaing are those which Philip the Fair bore from 1496-1504 and not those of his great-grandfather Philip the Good, which Wijsman suggests (p. 114) may be a subtle allusion to the period around 1500 when Antoine de Lalaing, Count of Hoogstraten, and his older brother Charles I, Count of Lalaing (1466-1525), held influential positions at the Burgundian-Habsburg court.

The irony of Jacques de Lalaing, the epitome of chivalry, being killed by a ricochet from a cannon ball, can be used to suggest a demarcation between medieval culture and the Renaissance but, as this volume demonstrates, the truth is more nuanced. As Capwell observes (p. 148), noblemen of Europe in the sixteenth century had to become literate military tacticians, able to deploy trained mercenary infantrymen as well as engage in cavalry actions. In addition, the Getty Lalaing is a manuscript produced in the age of print (the first printed version of the Livre des faits was not until 1634) which used elements from prints to vary the compositions of the earlier manuscripts (a stag hunt by Lucas Cranach, fig. 23, served as the model for the bull-baiting shown in Plate 6).

This monograph makes a sumptuous manuscript accessible to a wide audience. It is the first time that the illustrations have been made available in color (and the Getty has generously also put them on-line) and the translations bring Jacques de Lalaing’s life to the notice of an English-speaking audience. If I had a wish, it would be for additions rather than changes. The plot summaries are, by design, restricted to the texts that relate directly to the miniatures. Morrison notes (p. 104, n. 26) the “curious lacunae” in the choice of illustrations, and thus welcome additions would have been full texts relating to two significant but unillustrated events in Jacques’s chivalric career: his knighting by Philip the Good and his election to the Order of the Golden Fleece. Jacques was knighted on the second day of the contest with Sir Jean de Boniface (Plate 5) and the importance of this is demonstrated, as Stahuljak notes (p. 12), by a change in terminology; before he is referred to simply as “Jacky” and after as “Sir Jacques”. Absences can be illuminating and the failure to request a miniature to celebrate Jacques’s membership of this elite and prestigious order may support the identification of Jacques’s father, Guillaume, as the most probable patron of the original manuscript. Guillaume, unlike Jacques’s uncles, Simon de Lalaing (c. 1405-1477) and Jean de Créquy (c. 1400-1472), who feature prominently in the Livre des faits, was never elected to the Order (Blockmans, p. 56, for Guillaume’s disgrace). Brown-Grant identifies the verbatim reproduction of the letters of arms stipulating the conduct of combats as a stylistic trait that distinguishes the Livre des faits from other chivalric biographies; while her point is made by reproducing fol. 56 as Fig. 9, a translation would have been a useful addition.

The audience for this monograph should be wider than manuscript specialists, appealing to those interested in chivalry, the nobility in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Burgundy, and the role of literature in affirming status and lineage. It could usefully be read in conjunction with a previous monograph written by Morrison and Stahuljak, The Adventures of Gillion de Trazegnies: Chivalry and Romance in the Medieval East (Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015), demonstrating the hybridity between historical and pseudo-historical figures (indeed Gillion de Trazegnies is cited as a real exemplar of chivalry in the preface to the Livre des faits – Plate 1) and the different functions that chivalric literature could fulfil for its patrons.

Ann J. Adams

Romsey, Hampshire