The 2017–2018 Annual of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp is completely devoted to Paul Vandenbroeck’s writings on Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. The Annual is divided into two parts; the first section focuses on a study of the triptych’s left panel, and the second examines a series of major symbolic elements in the central panel. This Annual forms a follow-up to Vandenbroeck’s 2017 book on the Garden of Earthly Delight’s central panel: Utopia’s Doom: The Graal as Paradise of Lust, the Sect of the Free Spirit and Jheronimus Bosch’s So-Called Garden of Delights (2017; reviewed by this reviewer on the HNA website July 2018). Thus these two books provide an English-language duo that complements Vandenbroeck’s long list of prior publications in Dutch. Taken as a whole, Vandenbroeck’s writings unquestionably represent the most extensive and indispensible resource for scholars interested in one of the most thorny and fascinating issues in Northern European art of the early modern period: the iconography of Hieronymus Bosch.

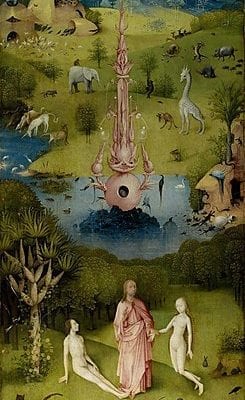

In the current volume Vandenbroeck begins his analysis of the Garden of Earthly Delight’s left panel by making a simple, but very insightful observation: that Bosch uniquely dedicates an entire panel of a triptych to the first human couple. Indeed, Bosch treats this theme not just in the Garden of Earthly Delights, but also in several other works (some lost). Vandenbroeck, quite rightly, identifies the key theme of the left panel as the marriage of Adam and Eve, rather than the Fall. One theological question raised by this marriage was that of the role of sexual activity and lust in Eden prior to the Fall. After surveying various theological positions, Vandenbroeck concludes that Bosch’s triptych accords with the opinion that lust was present in Eden from the beginning. This element of sexual desire links with the theme of procreation within marriage, which Vandenbroeck associates with the exuberant flora and fauna in the left panel, thus connecting Bosch’s depiction of the dragon tree, with its burgeoning branches and clinging vine, to God’s institution of marriage for the purpose of being fruitful and multiplying. His treatment of the dragon tree includes details about the importation of that tree from the Iberian peninsula into Northern Europe around 1450, as well as the history of European colonization of the Canary Islands, where these trees grow. This is just one of many demonstrations of protean intellect that Vandenbroeck brings to bear on this material and that makes this book so valuable to scholars studying Bosch from a wide range of methodological viewpoints.

Vandenbroeck associates the swarming animals in the Garden of Eden with the propagation of evil in the course of creation and procreation. As opposed to some scholars who interpret the Garden of Earthly Delights positively, he has long viewed the triptych as carrying negative meanings, identifying the monstrous animals in the left panel (e.g., the bird with three heads) as diabolical elements, and seeing the multitude of animals and swarms of birds as “a rampant propagation of multiform Evil.” He elucidates the pile of black matter at the base of the paradise fountain as the raw material out of which everything is generated, and the precious stones on top of the black stuff as products of nature’s creative power. In this triptych, according to Vandenbroeck, Bosch expresses the view that in the early days of creation, not only mankind, but nature itself, out of its basic matter, introduces an evil, sexualized, bodily impulse into the world. Indeed, in Vandenbroeck’s view, Bosch connected nature’s creativity to human, artistic creativity; in this way, he presents Bosch as a self-aware artist and the Garden of Earthly Delights’ theme, in part, as a meta-commentary on art itself.

The book goes on to analyze a number of other elements on the left wing in association with the themes of procreation, creation, nature, and evil. I found the section on the owl to be particularly compelling. Here Vandenbroeck – based especially on research about fowlers’ practices – is the first to unpack the meanings of the owl in the very specific contexts in which Bosch shows the bird in this panel: surrounded by other birds, within a Creation scene, and within a scene of marriage. Exploring all these dimensions of the context allows Vandenbroeck to elucidate multiple roles that the owl plays: as a symbol of conflict, as connected to the concept of the enticement of evil, as a marker of universal enmity, as a symbol of foolishness and sin, and as a symbol associated with illicit sexuality via the male sex. In this way, the owl becomes a core symbol for the left panel’s theme of marriage, which is divinely instituted by Christ (as shown on the left panel), but which (as shown in the center panel), becomes corrupted by those who turn God’s command to be fruitful and multiply into luxuria.

The second section of the book considers a large group of symbolic elements within the central panel, some of which are trademark features of the Garden of Earthly Delights, such as the strawberry; but other elements appear frequently throughout Bosch’s works, such as the crescent moon, fish, spheres, birds, and nakedness. As always, Vandenbroeck explores each motif from a variety of angles, considering an assortment of meanings, positive and negative, from a variety of cultural and artistic sources. This section is intended as closing supplement to the two-volume study, and it forms not just a coda, but also an overall reference guide for Bosch symbolism. This trove of information, like the strawberries that Bosch depicts in his Garden of Earthly Delights, is a source of delight. But unlike the strawberry, these delights are not transient and fleeting: scholars will be able to mine the densely-packed information contained in this half of the book and draw a multitude of benefits from it for many years to come.

Lynn F. Jacobs

University of Arkansas