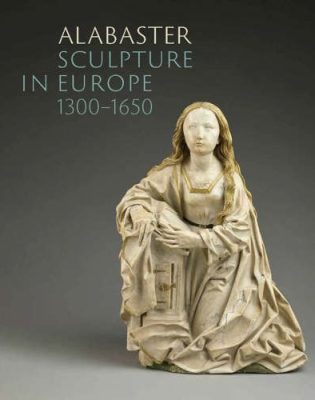

For much of the later Middle Ages and Early Modern period, alabaster was often the material of choice for sculptors in various European centers, creating works ranging from the intimate to the colossal. The stone is at once beautiful and confounding. Its luminous appearance can resemble marble, often to the point of being indistinguishable without technical analysis. At the same time, alabaster offers sculptors considerable advantages over marble, as it is far softer and considerably easier to carve. The term “alabaster” itself is nebulous, encompassing stones with different chemical properties and variable coloration, ranging from lily white to yellow or pinkish, sometimes with veins of other colors threaded through. Appropriately, then, Alabaster Sculpture in Europe, 1300-1650 is a complex and variegated production. Like the exhibition it accompanied, this catalogue encapsulates much recent scholarship on important individual works, it proposes new understandings of the reasons for the popularity of alabaster at particular times and places, and it offers compelling examples of the ways in which recent scholarship’s “material turn” might be fruitfully brought to bear on pre-modern art.

The exhibition was a magnificently sprawling affair, occupying a considerable amount of space within its host institution, M Leuven. It was clearly a monumental undertaking on the part of its organizers, Marjan Debaene (of M Leuven) and Sophie Jugie (of the Louvre), and their team. The catalogue mirrors the exhibition in being divided into several thematic sections, each of which consists of a brief introductory text, one or more scholarly essays on a facet of the topic, and catalogue entries for the relevant displayed objects.

The pieces grouped together in the clusters of catalogue entries partly serve to illustrate the issues addressed in the preceding essays. But the entries’ authors clearly also sought to ensure that the entries are, in a sense, free-standing – summarizing the current state of knowledge for each object, directing the reader to further bibliography, and so on. While necessary, this occasionally creates a degree of disjunction between the thematic essays and the catalogue entries. At times individual entries seem to pay little attention to their section’s theme, while other times their adherence to a particular theme tends to submerge additional topics that might themselves have warranted deeper, more systematic consideration. To cite but one example: the section on materiality includes examples of objects created by the same artist working in both wood and alabaster, illustrating a point made in the essay that alabaster is amenable to sculpting with the same tools and techniques that are used in carving wood. These include images of the Virgin and Child in boxwood and alabaster (cats. 3 and 4) produced by Maria Faydherbe (1587-1643) in the early seventeenth century. These works exemplify the point about the compatibility of techniques, but they might also have been deployed to shed additional light on the particularities of the situation faced by female artists like Faydherbe. This is not, of course, a failing of the volume, but simply a reflection of the necessary choices made in adhering to its organizational structure.

The first section of the catalogue considers the material of alabaster itself, beginning with Aleksandra Lipińska’s exploration of the cultural resonances of alabaster as material. Drawing on theories developed by James Gibson (in his 1977 Theory of Affordances), she describes the stone itself as having a kind of agency in conjuring up associations, fostering beliefs, and encouraging certain behaviors on the part of its users. Responses to the material were as variable as the material itself, and she wisely notes that “not only with respect to the geological origin, but also in reference to the cultural meaning, there should be no talk about alabaster, but rather about alabasters” (13). She bolsters her argument through a sensitive engagement with the work of modern and contemporary artists who have used the material, including Sofie Muller (b. 1974), whose works were represented in the exhibition and appear in the catalogue. As Lipińska notes, the varied responses to alabaster can be grouped into certain shared themes or approaches. Its whiteness conjured ideals concerning color; this included playing a role in developing concepts of racial identities as well as gender and class roles. The relative softness of alabaster enabled sculptors to work it in highly complex ways, inviting them and their audiences to engage in discourses of virtuosity. Lipińska notes as well that the stone could be perceived as fragile or delicate, as translucent, as pure, as exotic, and as flesh-like.

The next two essays draw on scientific forms of material analysis. Wolfram Kloppmann describes how isotopic analysis allows us to distinguish alabaster from marble, and to identify varieties of alabaster among stones that otherwise appear more or less identical. This new technology, refined only in the last decade or so, has been particularly helpful in mapping the geographic origins of alabasters, enabling much better understandings of pre-modern trade networks. It is also confirming perceptive intuitions of previous scholars: Kloppmann notes, for instance, that Kim Woods had sensed similarities between the stone used in objects associated with the carvers of the Rimini Altarpiece of the early 1400s and Tilman Riemenschneider’s shop about a half century later. Isotopic analysis has confirmed that they come from the same quarry, which must have been in Franconia – a fact worth considering in the context of efforts to localize the Rimini Workshop, for an understanding of early fifteenth-century trade links, and for the origins of Riemenschneider’s own craft.

Isotopic analysis involves the extraction of a small amount of material, which precludes its use on certain objects. In the next essay, a trio of experts – Judy De Roy, Laurent Fontaine, and Géraldine Patigny – consider X-ray fluorescence (XRF), a non-invasive technique of analysis. They note that this approach, too, has born significant fruit as in the case of André Beauneveu’s massive fourteenth-century statue of St. Catherine of Alexandria (cat. 2). The multi-talented Beauneveu worked in marble at times, and the exceptional scale of this piece led scholars to assume it was of that material rather than alabaster. XRF analysis has demonstrated that it is actually carved of alabaster, which may help scholars better understand the original context of the piece’s creation.

Subsequent sections of the catalogue consider the major categories of imagery created in alabaster throughout the period. The first of these discusses funerary sculpture. Jessica Barker draws on the earlier discussion of the various valences of alabaster to explore its use in tombs in England and on the continent. As she perceptively suggests, it seems likely that the ways that the stone could connote concepts associated by medieval Europeans with human flesh – particularly whiteness, delicacy, and transience – helped to drive the adoption of the material as a primary element in funerary monuments from the fourteenth century onward. Barker also astutely notes that the choice of alabaster allowed patrons to visually align their memorials with those of political allies or predecessors.

The next section is devoted to altarpieces, beginning with Stefan Roller’s account of works that have been grouped (more or less closely) around the Rimini Altarpiece, an exceptional ensemble of carvings in Frankfurt’s Liebieghaus Skulpturensammlung. Roller’s essay summarizes findings from the exhibition dedicated to that altarpiece in 2021, in which he played a leading curatorial role. He provides a concise overview of the relationship between the works that have been stylistically linked to the Frankfurt pieces, and sketches the persuasive argument for placing the core of the group’s production in the Burgundian Netherlands, most likely in Bruges, around 1430.

In the next essay, Lloyd de Beer tackles the extraordinarily prolific production of alabaster altarpieces in England from the late fourteenth until the early sixteenth centuries. These objects were in the past frequently dismissed as “provincial” or “crude” – a historiographic legacy that de Beer’s essay compellingly challenges. He succinctly describes the complexity of English production, which ranged from individual commissions by powerful patrons to “on spec” items made for a lively export market. Along the way, de Beer makes important points about how modern notions of “copying” and “influence” and the assumptions that accompany them pose major problems for our efforts to understand these works on the terms of the period that produced and used them.

The altarpieces section concludes with an essay by Carmen Morte García on alabaster altarpieces in Spain. García faced a daunting task: alabaster was used for centuries in Spain to create a vast number of extraordinarily complex altarpieces. Her essay understandably moves at speed through a great many examples, but succeeds in conveying the richness of the material it covers and the ways that these artists were embedded within international artistic networks.

The last major section of the catalogue deals with the broad topic of smaller objects made for use outside of purely ecclesiastical settings. Soetkin Vanhauwaert’s essay focuses on carved heads of St. John the Baptist – objects with obvious religious significance but designed for use by lay individuals in domestic settings. Vanhauwaert nicely sketches the ways that these objects were designed to evoke a dense web of associations, connecting the alabasters to relics, other images, notions of pilgrimage, Eucharistic concepts, and so on.

The catalogue concludes with a brief artist’s statement of sorts by Sofie Muller, the contemporary sculptor whose works were fruitfully deployed at strategic points in the exhibition. Intriguingly, several of Muller’s points echo observations made at the start of the catalogue regarding the ways in which the stone itself has a kind of agency. She notes, for instance, that nodules of alabaster often contain hidden veins of color that reveal themselves only in the process of carving and that, in doing so, have a role in determining the ways that viewers will perceive the resulting works. In particular, she notes that the variety of coloration encompassed by alabaster parallels the diversity of human appearance, making it extraordinarily evocative of flesh.

In short, everyone involved in creating this catalogue and the exhibition it records deserves praise. The volume covers a vast terrain, helpfully summarizing the current state of knowledge on a great many objects and providing a road map for further study by scholars and students of the material (and indeed of “materiality” writ large). In doing so, the catalogue provides a stellar example of the benefits of stepping outside of the intellectual taxonomies that so often constrain scholarship: our assumptions about the firmness of divisions between stylistic periods, geographic regions, and categories of objects. It compellingly demonstrates that those boundaries are far more permeable than they often might seem, and that they can distract us from important commonalities that transcend them.

Stephen Perkinson

Bowdoin College