Poor Albrecht Dürer had not been in his grave more than a day before his body was exhumed by a group of enthusiastic local artists, eager to acquire some relic of “whatever of Albrecht Dürer [that] was mortal,” to borrow from Willibald Pirckheimer’s epitaph on his tombstone. They took a death mask of the artist’s face and cut a lock of his hair – still surviving, in the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna, and originally owned by Hans Baldung – presumably before the body was interred Already in the very hours after his death, the artist’s cult status had begun.

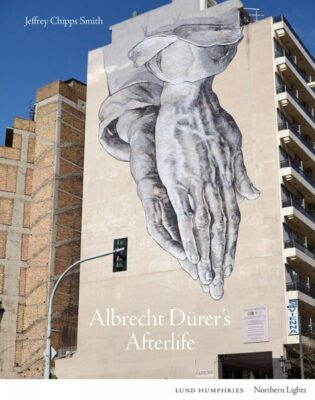

Much like the collectors who, in the decades immediately after Dürer’s death on April 6, 1528, toiled diligently to acquire a complete corpus of his prints as an encylopedic legacy of the great artist, Jeffrey Chipps Smith’s book Albrecht Dürer’s Afterlife amasses a comprehensive inventory of instances when the dead artist’s life and work provided future generations opportunities for engagement, emulation, admiration, and appropriation. Unlike other publications that have considered Dürer’s legacy specifically within the Early Modern period or among the German Romantics, for example, Smith takes the reader through these and other eras, including the twentieth century and right up to the visual culture of our current day: the Praying Hands re-envisioned as street art and Knight, Death, and the Devil as a full-back tattoo.

Albrecht Dürer’s Afterlife, part of the Northern Lights book series, is organized roughly chronologically, beginning with a whirlwind sketch of Dürer’s life and major accomplishments and the immediate years after his death. Chapters Two and Three cover the so-called “Dürer Renaissance” around 1570-1630. The first of these chapters chronicles the many princely and patrician collectors who sought to own Dürer’s works.[1] The latter chapter concentrates on artistic responses to Dürer’s works during these years, particularly in printmaking, including such topics as the Wierix brothers’ hyperaccurate copies of Dürer originals and Hendrick Goltzius’s engraved paraphrase of Dürer’s woodcut Circumcision. Chapter Four gathers textual evidence of Dürer’s reception prior to arond 1750, both in printed works by famous early art historians, such as Giorgio Vasari, Karel van Mander, and Joachim von Sandrart, as well as lesser-known writers, and a few private artifacts, such as humanist epistolary exchanges.

In Chapter Five, roughly midway through the book, we encounter the German Romantic movement and its nostalgic championing of Dürer. Smith ties the veneration of the “Dürer-Zeit” in early nineteenth-century Germany to anxieties surrounding the Napoleonic invasion and the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. Throughout that same century, as Chapter Six discusses, anniversaries of Dürer’s birth and death provided the occasion for elaborate celebrations and spectacles at various locations within Germany, with bespoke artworks created for the events.

“Dürer’s Institutional Canonization,” Chapter Seven, distills the content of Smith’s 2020 book, Albrecht Dürer and the Embodiment of Genius: Decorating Museums in the Nineteenth Century.[2] Dürer’s image was included in the programmatic décor for both princely and public museums that were established in Germany and Austria during this period.

Up to this point, Smith observes, Dürer had been mostly a phenomenon within German-speaking lands – as the art historian Heinrich Wölfflin would later note, “it is popular to think of Dürer as the most German of German artists.” Chapter Eight examines the later nineteenth century and the popularization of Dürer both within Germany and farther afield (for example, his image shows up in a porcelain display at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago in 1893). Smith credits much of this expansion of Dürer’s sphere of influence to advances in reproductive techniques, so more people could now encounter Dürer’s artworks through autotype photographic reproductions.

This ubiquity, however, took a decisive turn when Dürer, his art, and his hometown were appropriated for propagandistic purposes by the Nazi party, the topic of Chapter Nine. A poignant 1947 drawing by an American war correspondant of a decimated Nuremberg shows the city’s bronze statue of Dürer somehow remaining upright amid the surrounding wreckage. Smith’s final chapter then flies through a number of examples from the years since World War II, highlighting the myriad ways Dürer continues to live on in artistic, scholarly, and popular culture.

Certain chapters are more engaging than others – the tongue-in-cheek postmodern reimaginings of Dürer’s art that conclude the book are much more fun to read about than the somewhat dry cataloguing of information gleaned from provenances and inventories presented in Chapter Two – but Smith’s concise prose is convincing and clear throughout, and the 80 full-color illustrations admirably augment his discussions. Prior familiarity with Dürer’s oeuvre is helpful, however, since many artworks are mentioned but not illustrated.

Dürer’s own highly conscious self-fashioning no doubt contributed to the fame he enjoyed in life and the esteem in which he has been held after death. But the leitmotiv running throughout Smith’s book is how the story of Dürer and his art has been controlled by factors entirely external to the artist’s own efforts to secure his own reputation. As Smith recounts this history, Dürer’s likeness finds itself both in wholly expected and in altogether surprising places: on a (literal) pedestal in the form of many statues; complementing Raphael as his northern foil and artistic soulmate; as a character in stage plays and works of literary fiction; as the cult focus of a series of quasi-religious pilgrimages and festivals; as a hero of Germanness to the Nazis; in a digital camera advertisement; and as a Playmobil figurine. Smith highlights that the true testament to Dürer’s legacy is that each era has fashioned its own Dürer; that is, his genius and achievements have remained relevant throughout the centuries as a manipulable mirror for each contemporary situation.

Of course, the situation outlined above does not even take into account the exhaustive amount of scholarship that exists on Dürer’s work. Smith does touch briefly on the key players in establishing Dürer as a subject of serious art-historical inquiry – Moritz Thausing, Heinrich Wölfflin, Erwin Panofsky – but wisely sums up the fifty years since Matthias Mende’s Dürer Bibliographie (which lists 10,271 entries) by noting simply that “the output of scholarly and popular writings has increased dramatically” (122). Indeed, von Sandrart, in his biographical entry on the Nuremberg artist in the three-volume Teutsche Academie, published between 1675-80, could not have anticipated how enthusiastically his suggestion that Dürer’s “exceptional artistic merits, which provided such a wonderful guiding light to his successors, would furnish enough subject matter and material for a book devoted to his works alone” would be taken up by posterity (52). Albrecht Dürer’s Afterlife demonstrates that a consideration of Dürer solely in his role as “a wonderful guiding light to his successors” also furnishes enough subject matter and material for a book.

Catharine Ingersoll

Virginia Military Institute

[1] Also see Andrea Bubenik, Reframing Albrecht Dürer: The Appropriation of Art, 1528-1700 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013)

[2] Jeffrey Chipps Smith, Albrecht Dürer and the Embodiment of Genius: Decorating Museums in the Nineteenth Century (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2020).