Did you ever wonder how the particular names inscribed on the cornices of major museums in Europe and America were chosen when those civic institutions were built? This new book by Friederike Kitschen does not expressly address Northern European Old Masters, nor is it situated in the early modern period, but it does provide the answer to that puzzling question. Works entirely devoted to art’s historiography seldom get discussed in book clubs, but they are crucial to what—and whom—gets prized and studied in both museum collections and university curricula.

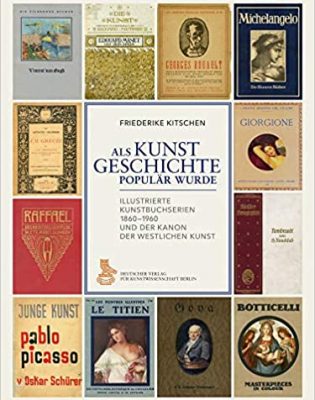

As Kitschen impressively and thoroughly lays out, the root cause, hidden in plain sight on library shelves, was a popular publication movement that started in the late 19th century with the rise of commercial photographic printing: the illustrated art book. Since the timing of these projects coincided with those same new museum buildings, they mutually reinforced a powerful, pre-selected roster of artists—almost always painters—in an exclusively European canon. Often slender, initially printed in black-and-white but later in increasingly accurate color images, these books enjoyed a sales boom in the early 20th century. Though long familiar; some volumes still remain quite useful to scholars, such as the more thorough series of Klassiker der Kunst (1904-1937).

Kitschen meticulously and systematically traces these series projects and their publishers, from pioneers in Berlin, London and New York, Boston, and Paris in the last third of the nineteenth century through their selections of early 20th-century modern art, chiefly in Paris but also in Germany, Milan, London, and even Japan. Often multinational alliances between publishers allowed images to cross borders and to receive new texts or translations.

She ends her survey with several versions of the emerging genealogy, the “Tree of Modern Art,” often associated with the version by Alfred Barr at the Museum of Modern Art, but already laid out as a (chiefly using French artists) by Julius Meier-Graefe in 1904, then painted by Mexican artist Miguel Covarrubias (for a 1933 Vanity Fair article), used in turn for a Japanese book cover, Cubisme, published in Tokyo (1937). Other, more dedicated series resisted this monolith, and celebrated instead the modern artists in their individual countries, such as Britain, Italy and Germany. But commercial considerations across borders usually accorded attention to the usual suspects and the Descent of Art.

Millions of copies of these popular, affordable books devoted to single artists democratized art appreciation across the globe (I can still remember similar portfolio volumes, issued in subscription as late as the 1950s from New York, Metropolitan Seminars in Art, written by such authors as John Canaday of The New York Times, and devoted to understanding major movements and the forms of individual works, if not individual artists). While Taschen, Prestel, and a few other publishers still carry on this venerable project, filling museum stores (lamentably, no longer proper “book stores” anymore), in our internet age the past flood tide of cheap monographs has largely ebbed. Meanwhile, we have lost some other major recent international contributors, such as Skira and Rizzoli.

The net result of such publications—reified in most U.S. introductory textbooks, which still tend to look more or less identical—was a repeated core of essential artists and artworks (and the exclusion of female artists and artworks from other parts of the world). Kitschen’s Epilogue sums up the roster. No anonymous need apply.

First and foremost, the canon is headed by Italian Renaissance artists (Leonardo, Titian, and Michelangelo, but also adding Correggio, Veronese, Fra Angelico, and Raphael, supplemented by Botticelli, Tintoretto, and, eventually, Caravaggio). Featured Netherlanders begin with Rubens, van Eyck, and Rembrandt, along with Hals and van Dyck, followed by Vermeer, Bruegel, and Bosch. Germans are rare, led by Dürer and Holbein, while Grünewald and Cranach remain more celebrated at home. Spain enters Velázquez, Goya, and El Greco, along with Murillo, who enjoyed greater popularity earlier (as his frequent appearance among the greats on US museums indicates). Some French names, such as Millet, have faded too, though Watteau and Claude endure, and of course from Manet to Matisse France dominates the more modern threshold. But familiar names and pictures, continually reinforced by reproductions, crystallized (fossilized?) into an exclusive, narrowly European canon of painters.

Martin Warnke declared in 1970 (quoted on p. 325): “Scarcely any other intellectual discipline invests so much energy in the production of popular literature as art history.” Until now, the historiography of that production has remained unexamined. So as we reflect on our tendency to concentrate our own research (and as university presses continue to publish that scholarship narrowly) on those same names, we can have our consciences pricked and our awareness heightened by Friederike Kitschen’s important research into our historiography.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania