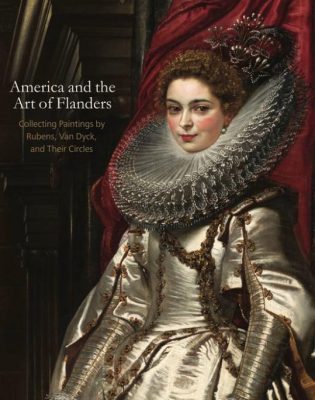

The scope for America and the Art of Flanders goes back to the symposium held at the Frick Collection in 2016. It comprises eleven essays by noted scholars who examine the American taste for the art of Rubens, Van Dyck and members of their circles over the past two centuries. The attention to the Flemish school, traditionally underrepresented in America compared to the Dutch school, dates back to the 1992 volume Flemish Paintings in America: A Survey of Early Netherlandish and Flemish Paintings in the Public Collections of North America, edited by the late Walter Liedtke, Curator of Dutch and Flemish Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, from 1980 until 2015, and his colleague at the Met., the late Guy C. Bauman.

The volume is introduced by Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr., longtime Curator of Northern Baroque Painting at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, who was instrumental in building the museum’s Flemish collection. During his tenure the number of Flemish paintings almost doubled from thirty-six to sixty-five. In 2005 he published the catalogue Flemish Paintings of the Seventeenth Century. Inspired by the gallery’s outstanding holdings of paintings by Van Dyck, he was instrumental in organizing, together with Susan J. Barnes and the late Julius S. Held, a highly successful exhibition of the artist in 1990-91.

The remainder of the book is divided into three sections. Part 1, The Early Years, The Formation of America’s Taste for Flemish Painting, begins with a study by Lance Humphries, Executive Director of Mount Vernon Place Conservancy, Baltimore, of Robert Gilmor, Jr. (1774-1848), a Baltimore merchant, who is often thought of as America’s first major collector of old master paintings, which he assembled over five decades, among them works by or attributed to Rubens and Van Dyck. From Gilmor, whose collection had its beginnings in the late eighteenth century, the book moves on to the early nineteenth century with an essay by Margaret R. Laster, former Associate Curator of American Art at the New York Historical Society, on Antebellum New York, focusing on two pioneering collectors, Luman Reed (1785-1836) and Thomas Jefferson Bryan (1800-1870). Reed, a self-made man and successful dry goods merchant, began collecting around 1850. His paintings became the nucleus of the New-York Gallery of the Fine Arts, New York’s first permanent art gallery that closed, however, and the paintings were placed in perpetuity at the New York Historical Society. Bryan, on the other hand, born in Philadelphia to great wealth, built his collection while living in Paris during the 1830s and 1840s. In 1853, he opened in New York his Bryan Gallery of Christian Art. Laster demonstrates how Reed and Bryan, for different reasons and in different ways, included Flemish art in their collections.

Next, Adam Eaker, Associate Curator in the Department of European Painting at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, surveys the work of Anthony van Dyck, the most sought-after Flemish artist in America. One of the most significant collectors of the Gilded Age, Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919), acquired eight paintings by Van Dyck, more than by any other artist. Six of these portraits formed the core of an exhibition Van Dyck: The Anatomy of Portraiture, curated by Eaker, together with Stijn Alsteens, held at the Frick Collection in 2016. Interestingly, American collectors did not conceive the cosmopolitan Van Dyck in terms of his Flemishness but rather saw him as the head of the “British School,” a status long claimed for him by British painters. Eaker’s essay is followed by Louisa Wood Ruby, Head of Research at the Frick Art Reference Library, who writes on the paintings of Pieter Bruegel the Elder and his sons in America. Of the elder Bruegel’s relatively few paintings, most of which entered princely collections early on, the most outstanding is The Harvesters in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Another important acquisition is The Wedding Dance, acquired by Wilhelm Valentiner (see below) for the Detroit Institute of Arts. The majority of Bruegelian paintings in America, however, are by Pieter Brueghel the Younger with slightly fewer works by Jan Brueghel the Elder.

Part 2, The Gilded Age and Beyond, is mainly devoted to the era of great wealth preceding World War I and the following decades. This section begins with an essay by Roni Baer, Distinguished Curator and Lecturer at the Princeton University Art Museum, and former William and Ann Elfers Senior Curator of European Paintings at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. With this contribution Baer returns to Boston and its nineteenth-century institutions, the Athenaeum, founded 1807, the Museum of Fine Arts, founded 1870 and, of course, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum with Rubens’s great portrait of Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel, acquired by Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840-1924) on the advice of Bernard Berenson. One of the great early acquisitions of the Museum of Fine Arts was Jacob Jordaens’s Portrait of a Young Married Couple, part of the estate of Maria Antoinette Evans (1845-1917), wife of Museum trustee Robert Dawson Evans, a mining and rubber magnate. The museum’s holdings of Flemish paintings was augmented, most importantly, by Rubens’s Mulay Ahmad in 1940 and The Head of Cyrus Brought to Queen Tomyris in 1941. In conclusion, Baer turns her attention to Boston collectors of the later twentieth century. For the Museum of Fine Arts, the most significant recent event was the promised gift, in 2017, of 113 seventeenth-century Northern paintings from the Van Otterloo and Weatherbie collections. Since the publication of this book, it should be noted that on November 20, 2021, the Museum of Fine Arts opened its Center for Netherlandish Art (CNA), exhibiting in seven renovated galleries nearly 100 paintings by seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish artists, many of them drawn from the 2017 gift. The center will house a library that will open to the public in January 2022. This is the first resource of its kind in the United States.

Esmée Quodbach, former Assistant Director of the Center of the History of Collecting at the Frick Collection, discusses the Flemish paintings acquired by John Graver Johnson (1841-1917), a prominent Philadelphia lawyer, whose collection is now under the stewardship of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Besides early Italian, Flemish and seventeenth-century Dutch pictures, he was especially fond of Rubens’s oil sketches rather than paintings, a feature in which he was ahead of his time (The Emblem of Christ Appearing to Constantine and Rubens, His Wife Helena Fourment and Their Two Children, Nicolaas and Clara Johanna, once again considered to be by Rubens, see J.S. Held, The Oil Sketches of Peter Paul Rubens, 1980, I, no. 296). In the early nineteenth century, Johnson was in contact with the German art historian Wilhelm Valentiner (1880-1958), a scholar of Flemish painting, and of Rubens in particular. By 1913-14 the collection had grown to almost 1,200 works. It was published in a 3-volume catalogue compiled by Bernard Berenson and Valentiner who catalogued the almost 300 seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish works, among them twelve by Rubens, six by Van Dyck, and nine by Teniers. In 1902, the Johnson collection was transferred to the Philadelphia Museum of Art as an extended loan, and in 1995, the paintings were integrated with the museum’s other holdings.

Dennis P. Weller, Curator Emeritus of Northern European Art at the North Carolina Museum of Art, where he was in charge of the Dutch and Flemish paintings for 25 years, discusses several men who played key parts as advisers and tastemakers for Flemish painting, including A. Everett “Chick” Austin (1900-1957) and Julius Held (1905-2002). For the American public the art of Rubens was not easy to accept. His women were considered too fat, he was too catholic for the largely protestant nation, and too tied to the royal courts. As director of the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida, Austin was instrumental in acquiring four large cartoons for Rubens’s Triumph of the Eucharist series; Held advised Louis A. Ferré in Ponce, Puerto Rico, in acquiring Flemish paintings (in 1965, Held published a catalogue of the collection). However, the main focus of Weller’s essay is on Wilhelm Valentiner already referred to above. He was instrumental in the acquisition of portraits by Van Dyck in Philadelphia, the National Gallery of Art, Washington, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Frick Collection in New York. His catalogue of the Flemish and Dutch paintings in the Johnson collection has already been mentioned. Valentiner also was instrumental in building the collections of Flemish paintings in Detroit, Los Angeles, and Raleigh. Unfortunately, some of the oil sketches in Detroit linked to Rubens are no longer accepted as originals.

Weller’s essay is followed by George Keyes’s account of several collections of Flemish paintings in the Midwest. After a long curatorial career in Minneapolis and Detroit, Keyes starts his narrative with the Detroit newspaper publisher James E. Scripps (1835-1906) who, in 1889, gave his collection of Old Masters – which included Rubens’s Meeting of David and Abigail – to the Detroit Museum of Art, later renamed the Detroit Institute of Arts, in the hope that others would be inspired to collect Old Masters and give them to public institutions as well. In later decades, prominent figures in the Midwest encouraged museums to acquire Flemish art, among them Wolfgang Stechow (1896-1974) at Oberlin College, Otto Wittmann (1911-2001), longtime director of the Toledo Museum of Art, who purchased Rubens’s great Crowning of St. Catherine, and most importantly, the above-mentioned Wilhelm Valentiner, who was the director of the Detroit Institute of Arts from 1925-1945, and through whose efforts the museum secured Rubens’s poignant portrait of his brother Philip Rubens and Hygeia, Goddess of Health.

Part 3, The Twentieth and Twenty-First Century: The Dissemination of Flemish Art Across America, opens with an essay by Alexandra Libby, Assistant Curator of Northern Baroque Painting at the National Gallery of Art, who writes about the formation of the collection of Flemish paintings at the museum, notably the donations of the Gallery’s founder, Andrew Mellon (1855-1937), and one of its founding benefactors, Joseph E. Widener (1871-1943). The Mellon and Widener gifts almost exclusively consisted of paintings by Rubens and Van Dyck, such as the enormous Daniel in the Lions’ Den and the beautiful portraits by Van Dyck, especially of his Genoese period. In recent years the artistic canon has expanded to include small-scale paintings by Adriaen Brouwer, Osias Beert, and Michael Sweerts, exhibited in the newly constructed Cabinet Galleries.

Marjorie (Betsy) Wieseman, recently appointed Curator of Northern European Paintings at the National Gallery of Art, and an expert on Rubens, examines patterns in the collecting of paintings by Rubens in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Observing that the master’s art represented much of what America’s Puritan settlers and colonial founders had rejected, it is hardly surprising that Rubens’s art found little resonance in this newly established country. The situation was complicated by the issues of attribution and authenticity. By 1947 when Jan-Albert Goris and Julius Held published their book Rubens in America, the number of “Rubens” works had increased to the point that it seemed advisable for a scholar like Held to separate the more secure attributions from the pretenders. But it was in the 1950s and ‘60s that the acquisition of Rubens paintings in American museums increased sharply, among them the spectacular Prometheus Bound in Philadelphia, The Crowning of St. Catherine in Toledo (already referred to) and Marchesa Brigida Spinola Doria in Washington.

The final essay is by Anne Woollett, Curator in the Department of Paintings at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, who discusses Flemish paintings, notably by Rubens, in Southern California, the most substantial ones found in the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Norton Simon Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. California business tycoons J. Paul Getty (1892-1976) and Norton Simon (1907-1993) ranked among the most formidable collectors of Flemish Baroque paintings, with a preference for Rubens. While California collections share the breadth of their comparable East Coast institutions, they cannot match their depth, due to their much shorter collecting history.

The volume does not cover the entire history of seventeenth-century Flemish painting in America but focuses on several important themes and on representative or remarkable collectors and their advisers, intending to inspire further research. The book is beautifully produced and illustrated.

Anne-Marie Logan

Easton, Connecticut