In general, Anthony van Dyck has been better served by catalogues than monographs. Any study of the artist will have as its point of departure the monumental 2004 catalogue raisonné by Susan Barnes, Sir Oliver Millar, Nora De Poorter, and Horst Vey, supplemented by the catalogue and companion volume of essays from the comprehensive exhibition held at the National Gallery of Art in 1990.[1] There have also been excellent exhibition catalogues devoted to such specific topics as Van Dyck’s early work, religious paintings, landscape drawings, English career and, indeed, portraiture.[2] Just before COVID-19 put a temporary stop to international loan shows, the Alte Pinakothek in Munich produced another doorstopper, rich with new insights derived from technical examination of the artist’s work.[3]

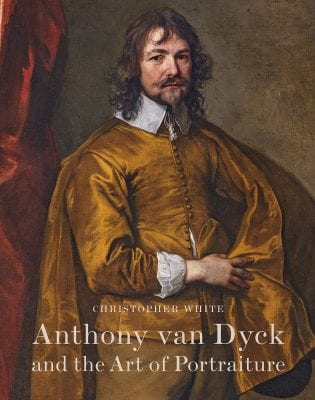

Van Dyck’s striking neglect in academic art history, at least in the Anglophone world, contrasts with this ample body of museum-based scholarship. I myself cannot recall being shown a single work by Van Dyck in my undergraduate or graduate coursework, despite specializing in early modern Northern European art. There is no volume devoted to the artist in the popular series by Thames & Hudson or Phaidon that are frequently used for college teaching. Christopher White’s new monograph on the artist’s portraits thus provides a welcome survey explicitly intended for a “non-specialist readership” (8).

White adheres to the traditional division of Van Dyck’s career into four geographic chapters: Antwerp, Italy, Antwerp again, and England. He provides an admirably lucid and thorough overview that deftly summarizes the existing literature, up through the most recent exhibitions. A particular strength of this account is the expansive treatment of Van Dyck’s Flemish and Italian work, which has often received short shrift in the English-language literature. The volume is lavishly illustrated and includes many seldom-seen works from private collections.

White’s approach is essentially comparative, built around a series of juxtapositions between Van Dyck’s portraits and those of other masters, most frequently Rubens. With a keen eye for compositional structure, the author is able to point out Van Dyck’s numerous departures from convention and precedent, making his formal innovations abundantly clear. Unlike many previous writers, White pays much attention to Van Dyck’s Northern sources and rivals, as well as the more obvious Italian inspirations. With a distinguished career at museums on both sides of the Atlantic, White has an encyclopedic firsthand knowledge of Van Dyck’s paintings, and his vivid descriptive passages transmit a contagious affection for the works under discussion. To cite just one example, here is White’s subtle analysis of the early pendant portraits of Frans Snyders and Margareta de Vos, now at the Frick:

“There is the extraordinary range and harmony of colour, here employed in a muted key – the purple curtains, hers a shade bluer; the grey of his pillar balances the colour of her column, touched with yellow and violet-grey reflections; his rich blue silk sleeves, caught in the raking light, enliven his sombre black doublet and cloak, brought into sharp focus by the brilliant white of his elegant lace collar and cuffs.” (60)

Reading passages such as this, I frequently found myself noticing new details of familiar portraits when looked at through White’s eyes.

In his preface, White attributes his love of Van Dyck’s portraits to a lecture given by Sir Oliver Millar in 1951. In terms of its methodology, this book is very much in line with art history as practiced in the mid-twentieth century, focusing largely on formal analysis and the identification of pictorial sources and influences. White notes that in “recent decades, much attention has been paid to interpreting Van Dyck’s British portraits in political and literary terms,” but asserts that his “priority … has been to gauge the artist’s intentions in producing the portraits rather than how they came to be perceived” (213). Yet politics and literature can contribute as much to the making of a portrait as they may structure its reception. With only scant attention to such contexts, White’s book frequently reads as a catalogue in narrative form.

Anthony van Dyck & the Art of Portraiture also restates certain biases against the artist that recur endlessly within the Van Dyck literature. These derive from early biographies by such writers as Giovan Pietro Bellori and Roger de Piles; in common with most other students of Van Dyck, White treats these texts as reliable documentary sources and not complex literary works, written decades after the artist’s death.[4] This leads him to repeat chestnuts about Van Dyck the narcissist, spendthrift, or womanizer and then to project these ad hominem critiques onto the paintings themselves. Where Wilhelm Valentiner, writing in 1950, said of Van Dyck’s New York self-portrait that the “gestures are more like those of a young society woman than of a painter,”[5] White declares, of the same painting, that “the gestures are decidedly coy – one could accuse Van Dyck of ostentatious posturing before the mirror” (68). White has a predilection for psychological readings of physiognomies that will strike some as overly speculative or anachronistic. For example, he infers from Van Dyck’s portrait of his wife, Lady Mary Ruthven, that she “was a loving and comforting companion” (275).

A contemporary undergraduate interested in such topics as Van Dyck’s play with gendered conventions or his depiction of Black sitters will find only a few passing references here. The lack of an adequate bibliography also hampers the book’s utility for students and as a spur to further research. Nevertheless, I hope that White’s palpable love of Van Dyck’s portraits, as well as the book’s many excellent illustrations, will stimulate future work on an artist about whom so much remains to be said.

Adam Eaker

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

[1] Susan J. Barnes, Oliver Millar, Nora De Poorter, and Horst Vey, Van Dyck: A Complete Catalogue of the Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004); Susan J. Barnes et al., Anthony van Dyck (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1990); Susan J. Barnes and Arthur K. Wheelock, eds., Van Dyck 350, Studies in the History of Art 46 (Washington: National Gallery of Art, 1994).

[2] Alexander Vergara and Friso Lammertse, eds., The Young Van Dyck (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2012); John Rupert Martin and Gail Feigenbaum, Van Dyck as Religious Artist (Princeton: Princeton University Art Museum, 1979); Martin Royalton-Kisch, The Light of Nature: Landscape Drawings and Watercolours by Van Dyck and His Contemporaries (London: British Museum, 1999); Karen Hearn, ed., Van Dyck & Britain (London: Tate, 2009); Stijn Alsteens and Adam Eaker, Van Dyck. The Anatomy of Portraiture (New York: The Frick Collection, 2016).

[3] Mirjam Neumeister, ed., Van Dyck: Gemälde von Anthonis van Dyck: Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, München (Munich: Alte Pinakothek/Hirmer, 2019).

[4] For an important account of Bellori’s Lives as a literary and programmatic text, see Elizabeth Cropper, “‘La più bella antichità che sappiate desiderare:’ History and Style in Giovan Pietro Bellori’s ‘Lives,’” in Kunst und Kunsttheorie: 1400-1900, ed. Peter Ganz et al. (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrasowitz, 1991), pp. 145–74.

[5] W. R. Valentiner, “Van Dyck’s Character,” The Art Quarterly 13 (1950): 87–105, quote from p. 88.