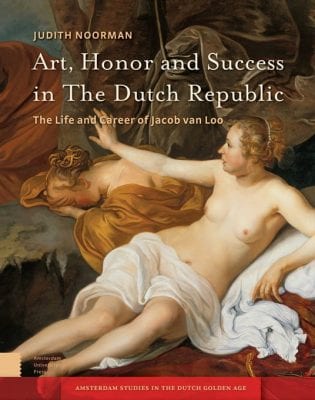

Judith Noorman’s ambitious new book provides an in-depth look at the life and career of Jacob van Loo (1614–1670), the mid seventeenth-century Dutch painter who is perhaps best remembered today for his paintings of nudes and for the murder he committed in 1660, which led to his self-imposed exile in Paris. In certain respects, the book functions like a traditional monograph (with Appendix A comprising a check list of works), as it offers convincing corrections to Van Loo’s biography and oeuvre that had been published in 2011 in David Mandrella’s ground-breaking study of the artist. However, Noorman’s principal task is to explore his art from an interdisciplinary perspective, particularly the aforementioned nudes, as well as his reputation and networks of patrons and, ultimately, the significance of the latter in the aftermath of the heinous crime that he had perpetrated at the height of his career.

Art, Honor and Success consists of an introduction, five chapters, and three appendices; wedged into the middle of the text are 110 mostly color illustrations of decent quality. The first chapter presents an overview of Van Loo’s biography, from his earliest years in Zeeland, through those of acclaim and financial success in Amsterdam, to the final decade of his life, spent in Paris. Certain aspects of his biography are revisited in greater detail in subsequent chapters. Suffice it to say that at this juncture, Noorman presents Van Loo as an artist of sociability and savoir faire who carefully cultivated such qualities in his relations with several notable patrons, including Willem Frederik, Stadtholder of Friesland – whose illuminating diary is quoted here (p. 30) – and members of the Huydecoper-Hinloopen family.

Chapter two investigates Van Loo’s artistic output and in doing so, rightly challenges long-standing and implicitly pejorative constructs of a master who supposedly approached art making eclectically by casually appropriating the styles and subjects of his peers. To the contrary, his genre paintings and especially his history paintings (the latter invariably including nudes) were quite innovative. By comparison, Van Loo’s portraits are certainly competent though hardly groundbreaking, which makes me wonder whether Noorman’s thesis is correct that he departed The Hague for Amsterdam owing to potential competition from other portraitists. As the author points out, Van Loo faced a similar level of competition in the largest city in the Dutch Republic. Regardless, Noorman’s investigation of Van Loo’s studio practices in painting portraits is as illuminating as it is invaluable.

The third chapter is dedicated to Van Loo’s clientele, who are surprisingly well documented in contemporary sources. Noorman uses well-known documents to great advantage along with others only recently discovered. Surprisingly, archival findings confirm that the artist was adept at pricing and marketing works to two economic levels of buyers. In particular, his paintings of nudes were in great demand and consistently commanded higher price points, thus securing Van Loo’s reputation in this arena. The Huydecoper-Hinloopen family remerge here; Noorman references a family diary that records Van Loo’s presence as guest in the Huydecoper house on at least two occasions in early 1660 (p. 94). Noteworthy in this chapter is her discussion of Van Loo’s Parisian career. Contrary to Mandrella’s assertion that Van Loo did not enjoy the same level of success in Paris (p. 91), Noorman demonstrates that his patronage in the capital consisted largely of Dutch diplomats and distinguished French clients and so can be considered an extension of that of his years in Amsterdam. The artist’s well-established and longstanding networks of patrons served him well there despite his exiled status. For example, Noorman outlines members of the Huygens family’s interactions with Van Loo in Paris, but they were actually among the painter’s oldest acquaintances.

Chapter four revisits the subject of an important exhibition that Noorman (and David de Witt) staged at the Museum het Rembrandthuis in 2016: the so-called academic nude. The discussion focuses upon two groups of artists in relation to “academies” (essentially, loosely organized joint drawing sessions with live models) in mid seventeenth-century Amsterdam: one centering around Rembrandt van Rijn and the other, around Van Loo, Govaert Flinck, and Jacob Backer. Noorman adroitly analyzes the aesthetic goals and achievements of these two groups in relation to the contemporary concept of welstant, an ambiguous term whose meaning gradually shifted as the century progressed. For Van Loo’s contemporaries, welstant in art signaled harmonious proportions in figures, captured in poses that were graceful and decorous. The author insightfully ties notions of welstant to behavioral codes among Dutch urban elites, which yields insights into the potential manner in which they perceived drawings and paintings containing female nudes.

In Noorman’s view, such images were meant to be enjoyed on an aesthetic level because they embody the academic ideal of welstant (p. 123). Their reception, in turn, was not at all negative since it was guided by stoic principles prevalent in elite circles that championed self control, especially over sexual appetites. The idea that sophisticated male viewers discounted temptation and licentiousness when viewing such art works is plausible but in my opinion, does not fully explain their enduring popularity throughout the century. Noorman herself (p. 124) notes the small size of Van Loo’s titillating Lovers (plate 44), which could fit into a drawer. Small-scale pictures suggest intimate viewing opportunities of a voyeuristic sort. None other than Constantijn Huygens, Jr. (1628–97), the secretary to His Majesty, William III, described one such opportunity in his diary. In an entry dated 9 September 1694, Huygens writes that a certain Peter Isaac, a member of the extended royal household and reputed whoremonger, showed him a little painting “of a woman in a very transparent chemise.”[1] Admittedly, the figure was not entirely nude, but it is difficult to believe that Isaac’s intentions in showing Huygens the little picture were aesthetically centered or temperate.

The final chapter of the book examines the manslaughter case that induced Van Loo to flee the Dutch Republic for Paris. Although Abraham Bredius had partially published documents pertaining to this infamous affair back in 1916, Noorman provides a full and more accurate transcription of the relevant legal materials in her Appendix C. More significant is the author’s interpretation of these tragic events within the broader social and cultural context of honor codes that were central to seventeenth-century European life. Honor in this period certainly referenced behavioral traits but as Noorman rightly argues, it was primarily an external concept bound up with reputation, namely, the opinion of the outside world (p. 128). In particular, she views the murder and Van Loo’s continued support among patrons and colleagues through the lens of seventeenth-century attitudes toward violence and homicide in which notions of honor were paramount. Van Loo himself was deemed honorable; honorable men did not engage in spontaneous fighting of the sort that had claimed the life of the artist’s victim. Therefore, Van Loo’s actions, as understood by his peers, were the result of mitigating circumstances, of threats posed by a dishonorable, unsavory character who bottled wine in vats for a living. Over the years, the painter had forged firm ties with powerful patrons who recognized his honored status as a gentleman. As a result, he could rely on their continued support and commissions despite his crime. Van Loo’s tenure in Paris was therefore a highly successful one. All of this makes for fascinating reading, even if Noorman errs in stating that little has been published on the concept of honor in seventeenth-century Dutch culture (p. 127 n. 4).[2]

In sum, Art, Honor and Success in the Dutch Republic: The Life and Career of Jacob van Loo makes many noteworthy contributions to our understanding of Van Loo’s career and art within the cultural milieus of the Dutch Republic and Paris. For this reason, it is disappointing that this otherwise important and beautifully produced book seems to have been rather carelessly edited, with some illustrations out of numerical sequence, several abbreviated citations in the endnotes that do not appear in the bibliography, and an index consisting solely of a register of names sans concepts and titles of works of art.

Wayne Franits

Syracuse University

———-

1. See further Wayne Franits, Godefridus Schalcken; A Dutch Painter in Late Seventeenth-Century London (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018), p. 120.

2. Recent studies treating the concept of honor in the early modern Netherlands include: Conrad Gietman, Republiek van adel. Eer in de Oost-Nederlandse adelscultuur (1555–1702) (Utrecht: Uitgeverij Van Gruting, 2010), pp. 31–102, passim; Bauke Hekman, ‘De affaire De Lalande-Lestevenon: feit en fictie over een spraakmakend schandaal in het zeventiende-eeuwse Amsterdam’ (Proefschrift, Universiteit Leiden 2010), pp. 36-37, 149–51, 184–85, passim; Ignaz Matthey, Eer verloren, al verloren: Het Duel in de Nederlandse geschiedenis (Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2012), pp. 65–75 (indirectly germane to Noorman’s fnal chapter); Marie-Charlotte Le Bailly, Een Haagse affaire. De verloren eer van Sophia van Noortwijck (1673–1710) (Amsterdam: Balans, 2013); Rolf Hage, Eer tegen eer; een cultuurhistorische studies van schaking tijdens de Republiek, 1580–1795 (Hilversum: Verloren, 2019), pp. 33–100.