Bronze sculpture of the late sixteenth century tends to be associated with Italy, specifically with the work of Giambologna, so an exhibition of bronzes originating mostly from southern Germany challenges long-standing assumptions about sculpture north of the Alps. The 2015 exhibition at the Bavarian State Museum in Munich brought together an astonishing number of close to eighty bronzes by Giambologna and many of his most talented students, including Hubert Gerhard and Adriaen de Vries. Also included were preparatory drawings, engravings, archival documents, as well as a guidebook, Merkur und Bavaria. Städteführer zu den Bronzen der Spätrenaissance in München und Augsburg, which allowed for a self-guided tour of works still in situ. In addition to ample illustrations throughout the accompanying essays, the catalogue contains seventy-eight color plates, enhanced by numerous details and multiple views that simulate the experience of the Mannerist figura serpentinata.

Five essays provide a comprehensive narrative to the exhibition, beginning with Dorothea Diemer’s overview of sculpture in Munich and Augsburg around 1600. Diemer, author of a definitive 2004 monograph on the sculptors Hubert Gerhard and Carlo del Palagio, summarizes bronze casting north of the Alps. As Diemer notes in her essay, large-scale bronze casting is expensive and requires technical expertise that only such wealthy and powerful patrons as the Bavarian dukes or the Augsburg banking family, the Fuggers, could have underwritten. Diemer’s essay admittedly revisits material covered in her Gerhard/del Palagio monograph, but her summary of this little-known field is essential to understanding the unique confluence of patronage and artistic talent that fostered a unique period of intense productivity of bronze sculpture in Germany. From the Wittelsbach Fountain, the Perseus Fountain, and the flying figure of Mercury, all in the Residenz, to the imposing St. Michael Defeating Satan on the façade of St. Michael’s Church, to the multi-figured Wittelsbach grave monument in the Frauenkirche, the prodigious volume and quality of public art from the Munich workshop is staggering when brought together in this one volume.

While most of the ruling elite exchanged small Kunstkammer objects, one of the most notable gifts to the Wittelsbach family came from the Medici, who presented their cousins north of the Alps with a life-sized crucified Christ by Giambologna that still hangs in St. Michael’s Church. The Bavarian connection to the Medici was cemented by the marriage of Johanna of Austria, sister-in-law to Duke Albrecht V of Bavaria, to Francesco de’ Medici in 1565. This magnificent wedding, attended by both the young Duke Ferdinand of Bavaria and the collector and Augsburg banker Hans Fugger, proved to be the catalyst for a decades-long relationship with the workshop of Giambologna, whose students Hubert Gerhard and Adrian de Vries then wound up working for the ducal court in Munich and the imperial court in Prague, respectively.

A second generation of German sculptors, including Hans Reichle and Hans Krumper, would be sent to Florence by Duke Maximilian I in order to provide the Munich court with its own crop of bronze specialists. Because of patronage by the Fugger family and the Wittelsbach dukes, Gerhard’s influence spread rapidly, resulting in commissions for major civic fountains from the city council of Augsburg and numerous private commissions throughout southern German cities and estates.

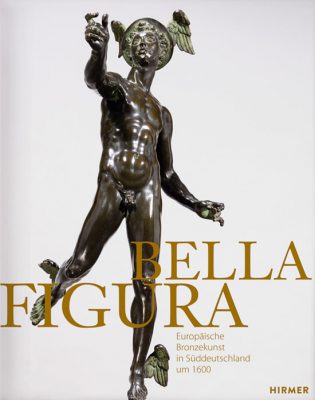

The center of the exhibit was Giambologna’s Flying Mercury (1580), on loan from the Bargello in Florence. The second essay, by Jens Ludwig Burk, deals exhaustively with issues of influence and style, seeking out every iteration, both large and Kunstkammer-sized, of the flying messenger of the gods that brought the genius of Giambologna into the hands of the northern collectors. Dimitrios Zikos’s essay takes a close look at the influence of Giambologna on art in Bavaria, tracing artistic connections as well as the equally important exchange of gifts and artists that resulted from diplomacy and “Kunstpolitik.” Sylvia Wölfle examines the central role that Hans Fugger played in introducing an Italianate villa style to Germany. The classicizing bronze fountain that he commissioned for the courtyard at his castle at Kirchheim not only reflected his wealth and erudition but also demonstrated his aristocratic ambitions.

In the final essay, Christian Quaeitzsch discusses reception and dispersion of the Munich bronzes over the next several centuries. Along with his brother Ferdinand I, the reigning Duke William I was the main force behind Wittelsbach patronage of large-scale bronzes. When he resigned in 1597, due in great part to his enormous debt, his son Maximilian I took on a nearly bankrupt state that saw the dismissal of almost all foreign artists who had made up a vibrant artistic scene in Munich in the 1590’s. But Maximilian, an astute and passionate patron of the arts himself, well understood the power of art to convey the prestige and influence of his dynasty. Nevertheless, rather than commission new works, Maximilian repurposed his father’s and his uncle’s personal memorials to new roles that would emphasize dynasty over personal biography.

Under Maximilian I, an ostentatious bronze grave ensemble for his father, Wilhelm V, was recast as a monument to the dynastic founder, Otto III. A multi-faceted fountain that had graced the courtyard of his uncle Ferdinand’s city palace was moved to the courtyard of the Munich Residenz, and the dramatically rearing equestrian statue (lost) at its center was replaced by a much less dynamic standing figure of Otto III. While Quaeitzsch makes a good case that the changes reflected Maximilian’s new emphasis on dynasty, one might wonder if, given the loss of Hubert Gerhard due to budget cuts, reinstalling the precariously balanced equestrian was simply beyond the technical abilities of the next generation.

The occupation of Munich by Swedish troops during the Thirty Years War could easily have been the end of many of these works, but it is a testament to the value that Maximilian placed on them as markers of the wealth and prestige of his capital city that he had the foresight to evacuate them to safety. Despite losses due to looting or the melting down of bronzes, the sheer number of surviving civic monuments and private objects attests to a sophisticated network of patronage, princely exchange, and artistic influence that spread out from Florence and found fertile ground in Munich. The ties between Florence, Munich, Augsburg, Innsbruck, and Prague created an intricately connected world of elite patronage in this most elite of mediums. Yet as several of the essays reveal, while family connections played a large part in this brief period of incredible productivity, it was also the obsession and will of the Bavarian dukes and the Fugger family that created a brief but potent flowering of the art of bronze casting in southern Germany around 1600.

Susan Maxwell

University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh