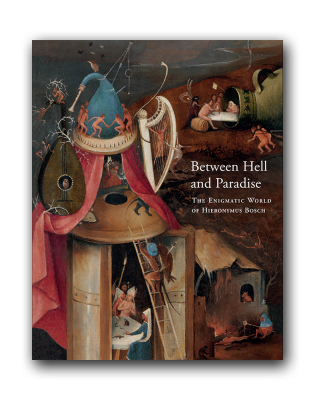

This book represents the first major exhibition catalog produced after the 2016 celebration of the 500th anniversary of Bosch’s death, which occasioned the publication of catalogs from exhibitions in ‘s-Hertogenbosch and Madrid. Like the Madrid catalog, the 2022 Budapest catalog begins with essays, most written by the same distinguished scholars who contributed to the earlier volume. Of the four essays in the Budapest catalog, two have thematic content, and two focus on individual triptychs. Although the two triptychs highlighted in these latter essays—the Lisbon Temptations of St. Anthony and the Garden of Earthly Delights—were not included in the exhibition, copies after both were.

Larry Silver’s essay, “Bosch and the World of Sin,” provides a strong opening to the book by giving an overview of Bosch’s oeuvre, centering on the critical issue of how Bosch infuses the Netherlandish tradition with a new sense of evil and pessimism. The essay begins with an in-depth study of evil within the Prado Adoration of the Magi; one notable claim here is the association of the semi-nude figure in the stable (the subject of much scholarly debate) with Jewish stereotypes. The focus then turns to a consideration of Bosch’s interest in the origins of evil in works that depict the Fall of the Rebel Angels and an already corrupted Eden. The final section considers Bosch’s use of caricatures to emphasize depravity in scenes of Christ’s Passion and Bosch’s depictions of the temptations of sin within worldly life in the Haywain, Garden of Earthly Delights, and Wayfarer Triptychs—and on how these works influenced other artists, especially Quinten Massijs.

Erwin Pokorny’s, “Illuminated Manuscripts as a Main Source of Hieronymus Bosch,” argues for a deeper connection between Bosch’s work and manuscript illumination than previously thought. The author advances not only familiar claims that Bosch brings the drolleries in the margins of manuscripts into his paintings, but also proposes that Bosch borrowed specific motifs, ideas, compositions, and stylistic techniques from manuscripts to the degree that Bosch could well have trained as an illuminator. While Pokorny’s interpretation of the meaning of the Garden of Earthly Delights is somewhat unclear and peripheral to his topic, his essay raises compelling points about how illuminated manuscripts could be a source for Bosch’s oversized fruits; his depiction of flowers and hybrids; and his strange creatures, figure types, and thematic combinations. A particularly effective argument is Pokorny’s claim that Bosch’s practice of depicting figures with items on their heads could be derived from symbolic crests with the elimination of the armored helmets that normally accompanied them.

Eric De Bruyn’s, “Hieronymus Bosch’s Lisbon Temptations of Saint Anthony Triptych and Its Written Sources,” provides important insights by laying out the full range of sources on St. Anthony’s life and explaining how the main events in the triptych link to specific texts, notably: the image of the saint lifted in the air and carried back unconscious; the appearance of Christ to comfort Anthony; the naked female trying to seduce Anthony; and the devil-queen feeding the poor and sick (a motif usually interpreted as a Black Mass). While De Bruyn’s arguments that some of the more obscure secondary scenes also relate to the written texts are thought-provoking, questions do arise in the case of recurrent motifs, such as the fish: is it justified to read the fish in the Temptations of Saint Anthony specifically in relation to Anthony’s association of fish out of water with monks in the world, and if so, how does that affect one’s reading of fish that appear frequently elsewhere in Bosch, for example, in the Garden of Earthly Delights and the Hay Wain?

The final essay, by Reindert L. Falkenburg, “In Conversation with the Garden of Earthly Delights,” represents a development and consolidation of the fascinating interpretations he presented previously in his 2011 book The Land of Unlikeness and in his essay of the same title in the 2016 Prado catalog. His main argument is that the Garden of Earthly Delights—which, he believes, was commissioned by Engelbert II of Nassau, a central figure at the Burgundian court—should be understood within the context of the display of courtly magnificence and the performance of amorous behavior within courtly circles. But the courtly context, on Falkenburg’s view, explains not only the sexual content of the triptych, but also its religious elements, because, like some lavish courtly displays, the Garden of Earthly Delights intertwines courtly and religious themes. Falkenburg sees the key religious theme here as that of seeing versus not seeing, that is, whether one is blind to the corruption of God’s original creation or else goes through life in a dream vision, deluded by the wonders of the world, unaware of the evil lurking just under the surface.

The rest of the volume is devoted to very informative catalog entries written by a team of scholars. The entries are divided into seven thematic sections, each of which fully integrates paintings, drawings, prints, and, occasionally, sculptures, and which places Bosch’s works in dialogue with those of his predecessors, contemporaries, and followers—characteristics which represent a distinctive strength of this catalog compared to the 2016 catalogs. The main topics and key Bosch works treated in this section are: 1) Bosch’s hometown of ‘s-Hertogenbosch; 2) satire, which includes Bosch’s Paris Ship of Fools and the Yale Allegory of Intemperance; 3) the Endtime, which includes the Venice Vision of the Hereafter panels, the Bruges Last Judgment, and the Vienna Hell Ship drawing; 4) the lives of the saints, which includes the Madrid St. John the Baptist and the Berlin St. John the Evangelist, and which argues convincingly against their inclusion in the Adriaen van Wesel altarpiece; 5) the imitation of Christ, which includes the New York Adoration of the Magi, and the Frankfurt Ecce Homo, the latter of which is juxtaposed with the Ecce Homo in the Hours of Engelbert of Nassau as an influence; 6) the Garden of Earthly Delights, which includes two copies after the famous center panel (one, damaged, from Budapest; the other, previously unexhibited, from a private collection) of this triptych and works that might have served as sources. The final section, 7) the artistic legacy of Bosch, closes off a fine catalog, which provides many new insights into Bosch’s paintings and drawings—and especially into the cultural and artistic context in which they were produced.

Lynn F. Jacobs

University of Arkansas