In recent decades, art museums in Europe and North America have increasingly staged exhibitions contextualizing the multi-dimensional nature of our shared cultural heritage. The decision to mount Black in Rembrandt’s Time, for which the Rembrandthuis should be applauded, exemplifies this trend. The 2008 Amsterdam exhibition Black is Beautiful: From Rubens to Dumas, catalogue co-edited by Elmer Kolfin and Esther Schreuder, was pioneering in this regard, influencing the present, more focused project. Many people just discovering the topic will certainly find the new exhibition and publication enlightening. Those familiar with the material, however, may find the thesis less than optimally served by the works of art chosen for display. (Since the health crisis has precluded my traveling to Amsterdam, this review addresses issues raised by the catalogue and object selection only.)

The exhibition, the idea for which was first proposed by Stephanie Archangel, consists of 49 works of art: 10 paintings, 6 drawings, 1 sculpture, and 32 prints. No Rembrandt paintings are included, though eight are illustrated in the catalogue. The foreword, introduction, and four featured essays are accompanied by short interventions. The last four pages, “Here and Now,” introduce striking images by four contemporary Black artists, but these are not discussed and seem an afterthought.

The foreword by Lidewij de Koekkoek, director of the Rembrandthuis, lays out the goal: the representations of Black people by Rembrandt and other Dutch artists, first of all in Amsterdam and then in the rest of the Republic, in the period 1620–1660, during Rembrandt’s working life. The central message is: “black people were already present in the seventeenth-century Netherlands, here, in this neighbourhood, in art, and in Rembrandt’s work.” (5) The exhibition’s audience-facing approach – its emphasis upon relevancy inherent to the public humanities – is enhanced by its setting, a house museum in a neighborhood long inhabited by many poor West Africans and other immigrants.

The catalogue’s initial essay by Elmer Kolfin introduces social and historical issues that underlie the exhibition. The author begins with Dutch participation in the African slave trade and harsh slavery conditions in Dutch colonies, issues about which many at home knew little, and which were generally suppressed by Dutch painters. As a result of this trade many Blacks initially came to the Netherlands either as seamen or servants. For those enslaved leaving Brazil or the West Indies, their arrival in a country where slavery had no legal standing meant liberation. How were these new immigrants received by the country’s established residents? It would depend upon their skills. For example, I suggest that the cited studies of Black musicians were drawn while playing a traditional role in the 1638 entry of Marie de’ Medici. In a subsequent essay, “As if they were mere beasts,” author Stephanie Archangel presents the gloomy picture derived from travel literature. Kolfin, however, judiciously notes the lack of evidence that negative characterizations actually informed the thinking of most Amsterdammers.

Conditions of life for West Africans in Amsterdam are addressed by historian and archivist Mark Ponte. Through analysis of archival records, Ponte sheds light on the legal status, circumstances of arrival, housing, and financial situation of the city’s Black immigrant population. He shows that Pieter Claesz Bruin from Brazil accumulated debts in inns frequented by whites, implying a type of social mixing for which the visual arts provide no evidence. Dissecting these matrices of relationships suggests to Ponte that the figures in Rembrandt’s Two Africans (1661) may be the brothers Bastiaan and Manual Fernando. The possibility of retrieving their names is thrilling.

“The Black Presence in the Art of Rembrandt and his Circle” by David de Witt encompasses material that is the best and least known to the public. The chronological progression begins with the foundational subject for Rembrandt and his circle, the Baptism of a stiff, distant Ethiopian and ending with the Two Africans with its moving immediacy. Between these poles De Witt sees many inclusions as touches of exoticism, similar to Rembrandt’s collection of Kunstkammer objects – a nice insight. The line of argument draws on a comparison with artists in Rembrandt’s circle, such as Lastman, Lievens and Flinck, but the inclusion of the Haarlem painter Hendrik Heerschop (1626–1690) is a stretch.

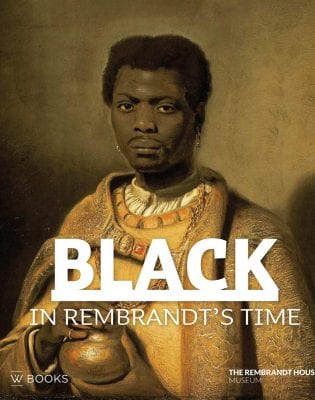

Heershop’s compelling King Caspar (or Balthazar), 1654 (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie) was a great choice for the cover, but in the text the painting is simply referenced as a tronie and the artist’s approach as “incorporating Rembrandt’s handling and subjects into his work.” Rembrandt is not known to have painted any of the three kings singly, and perhaps Heerschop’s Black king, like his history painting, is better compared with the Haarlem circle of Peter de Grebber. For example, the king’s mantle is a typical if costly version of the cope worn by Catholic priests in seventeenth-century Haarlem and adapted by de Grebber and others for monarchs as well as priestly figures. His gold ring begs to be noticed. If a workshop prop, it would be elaborate. Since no other Black figure by Heerschop is known, efforts to tease out a plausible backstory are warranted. Perhaps this portrayal of a dignified Black man with such a direct gaze was not painted as a tronie of King Caspar (or Balthasar), but as a portrait historié of this particular Black man in the guise of the Black King commissioned by the sitter. If the man were white, this possibility would be obvious.

My major disappointment in the enterprise regards the works of art chosen for exhibition and discussion in the catalogue. In my view, the show contains too many works by members of Rubens’s circle and by Wenceslaus Hollar (1607–1677), leaving important Dutch works unmentioned or unillustrated in the catalogue, skewing the historical picture. The typical format for the inclusion of Blacks in finished works of art was as subordinates to white people in portraits or history painting, all from the perspective of the white gaze. The exhibition and catalogue feature many images of this kind. But there are also exuberant Dutch paintings of the king and queen of Ethiopia and Congolese envoys resplendent in their own attire. Closer to home, if archival documentation of serious abuse has not come to light, a weighty overarching power structure remained. Why not illustrate the infamous 1632 painting by Christaen van Couwenbergh of a terrified naked black woman molested by laughing white men in a bordello (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg)? That is also being Black in Rembrandt’s time.

Joaneath Spicer

Walters Art Museum