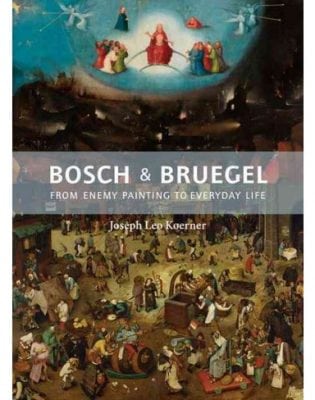

Deftly argued and fluently written, Koerner’s enthralling book is a revised and amplified version of the A. W. Mellon Lectures he delivered at The National Gallery of Art in 2007. He juxtaposes Bosch and Bruegel in order to distinguish between them, drawing a line in the sand between the paradigms of art they are seen respectively to epitomize. As is typical of Koerner, his account is many-sided – by turns art historical, anthropological, and philosophical – yet structurally coherent. Although he touches upon many works by both artists, several chapters are devoted to specific paintings, and they not only brilliantly summarize the state of the question on these images, but also offer many new insights. Indeed, the chapter on The Garden of Delights (1504), entitled “The Unspeakable Subject,” puts forward an alternative view of the triptych, different from Reindert Falkenburg’s (in his monograph The Land of Unlikeness) but no less convincing. Koerner’s book, like his lectures, was written to engage a wide spectrum of readers, not just historians of Netherlandish art, or even art historians generally, but anyone fascinated by the strangeness of Bosch’s inventions and the worldliness of Bruegel’s. Published in 2016, Bosch & Bruegel has already circulated widely and deserves to garner the largest possible readership.

Summarizing the book’s arguments in a brief review, I would distill its main point of comparison as follows. Whereas Bosch, as the Latin inscription on his famous drawing The Field Has Eyes, the Forest Has Ears (ca. 1500) demonstrates, placed a premium on artistic invention, his theory and practice of poiesis ultimately subordinate human inventiveness to the prior and inimitable inventiveness of God. As Koerner repeatedly contends, Bosch likely construed inventio and its source ingenium as expressions or, better, symptoms of sinful pride; the artist’s pride generates fantastical, counter-natural things, by contravening God’s command (Genesis 1: 98) “to be fruitful and multiply.” Thus, pictures such as The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (ca. 1500) or The Last Judgment (ca. 1504) present themselves as if seen by a bellicose, vengeful God intent on punishing the manifold sins that Bosch so inventively and sardonically ascribes to human solipsism and self-serving resourcefulness; on the other hand, they indict the artist himself, calling into question the generative but non-procreative use he makes of his redoubtable faculty of invention. Nowhere is this more evident, as Koerner observes, than in Joseph de Sigüenza’s peculiar elision of Satan and Bosch in his encomium of a Temptation of Saint Anthony by the artist, translated by Koerner (170). Here the reference to Satan becomes suddenly a reference to Bosch, confounding the devil’s trickery with the painter’s artistry. Bolstered by discussion of Bosch’s exegetical usage, such as the paraphrase from Deuteronomy 32: 20 (Song of Moses about God’s enmity) in The Seven Deadly Sins and the citation from Psalm 33 in the closed state of The Garden of Delights, Koerner’s reading of Bosch not only closely aligns with Sigüenza’s but is at heart Augustinian. Thus Koerner applies the moniker “enemy painting” to Bosch’s art.

Koerner’s insightfully insists that Bosch, even while anchoring his project of art in a theology of the image shaded by Augustinian ambivalence, in other respects valorized the status of the inventive artist as sui generis. Bosch indicts prideful image-making, but at the same time repeatedly calls attention to himself: punning self-portraits are embedded everywhere in his paintings and drawings, especially drawings such as The Field Has Eyes and The Owl’s Nest (ca. 1510). Similar self-reference, Koerner argues, is discernible in such paintings as The Garden of Delights, where Bosch reveals how the God-given fecundity of nature, exemplified in the closed state of the triptych, gives way to rampant libidinous desire, laid bare in the open state, before finally petering out in the hell-bound sterility of the Tree-Man (242).

What then of Bruegel, who is dubbed the painter of “everyday life”? According to Koerner, he differs fundamentally from Bosch in that his art is more anthropological than theological, based not in Christian doctrine but in the portrayal of human culture and especially the indigenous culture of town and country. Koerner’s conception of Bruegel can thus be situated in a lineage from scholars such as Justus Müller Hofstede, Svetlana Alpers, and Ethan Matt Kavaler who respectively posit Bruegel as an exponent of a neo-Stoic view of nature writ large and as an early advocate of an ethnographic perspective on human affairs. Viewed through this lens, Bruegel is seen to forecast the primary condition of modernity as defined by Martin Heidegger – the depiction of human life as a distanced subject and of nature as the indifferent stage upon which human experience is fashioned and encountered.[1] For Heidegger, the index of distanced subjecthood is the mediated perception of nature as a pictorial phenomenon: the world is construed as a representational construct, and the viewer of the world visualizes it in the form of a picture, as a Heideggerian “world picture.” Koerner asserts that the panoramic landscape format, in constituting the “world as a view” on the model of the cartographic landschappen promulgated by Bruegel’s friend Abraham Ortelius, is the form that this ethnographic point of view takes for Bruegel; this pictorial format, whether it comprises village streets or metropoles, allows Bruegel to situate himself at one remove from himself and his subjects, subsuming everything they do into the register of ethnography. One crucial consequence of this mode of viewing is that allegory no longer can be latently discernible in the divinely mandated order of the world; rather, allegory becomes a matter of performance and painting the medium for such performance.

On this account, the Battle between Carnival and Lent (1559) is not a newly minted allegory. On the contrary, “in [Bruegel’s] hands seasonal entertainment [is] designed and performed by villagers. … not Bruegel’s allegory but theirs, these particular people whose customs and costumes he meticulously records in paint.” (338) By the same token, the villagers dancing their way toward the gallows in The Magpie on the Gallows (1568) do not so much personify ignorance toward danger or defiant disregard for the oppressive rule of law; instead, they perform the proverbs “To dance to the gallows” and “To shit on the gallows”, and in this sense, their symbolic agency is enhanced. Koerner emphasizes the scenario that Bruegel imagines: “they … knowingly behave in a proverbial way, as if the dancing trio … suddenly had the notion, based on a saying or song, of dancing instead under the gallows.” (363) A principal side-effect of the ethnographic mode is the close attention Bruegel pays to manufactured artifacts of all kinds. (By contrast, Koerner points out that Bosch’s artifacts are mostly fashioned by nature rather than human-made.)

At places in Bruegel’s oeuvre, however – Christ Carrying the Cross (1564), for example – the Heideggerian model of the “world picture” breaks down, and the picture seemingly turns to face the beholder, gazing with the intensity of the eye of God in Bosch’s The Seven Deadly Sins and addressing us with a directness of religious charge that dissolves the ethnographic frame of reference. The mourners in the right foreground, as Koerner astutely notes, by turning out of the image toward the viewer, enact Christ’s command (Luke 23:28-31) to weep not for him but for themselves. Koerner seems to claim that a distancing effect is partly operative even here, for the mourners are portrayed “art historically,” in the manner of Rogier van der Weyden above all. (294) But here, I would argue, style functions rhetorically as an instrument of ethopoeic and pathopoeic intensification that momentarily dissolves the ethnographic framework, bringing artist and viewer directly into mutual contact. It may be worth mentioning that there are aspects of Bruegel’s pictorial production that Koerner leaves largely unconsidered: for instance, the exegetical and hermeneutic commitments richly on view in the artist’s explorations of biblical themes – the Resurrection (ca. 1560), the Death of the Virgin (ca. 1564), Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1565), and the Seasons of the Year (1565). [2]

Koerner’s discussion of Bosch, in addition to being more extensive than his discussion of Bruegel, is more replete with novel insights, three of which I want to underscore in closing. First, he persuasively reads the Antichrist in the center panel of the Adoration of the Magi (Epiphany) (ca. 1510) as a generalized embodiment of the denial of Christ’s divinity (John 2:19), and accordingly, an allusion to the threat of self-deception. Second, his tracing of Adam’s line of sight in The Garden of Delights, as a vector of desire across the center panel and finally to the ruinous Tree-Man, who mirrors Adam’s face and gaze, allows Koerner to track the triptych’s thematic of prideful vision in a manner that effectively unites its three parts. Equally compelling is Koerner’s subtle observation that the fine strokes of vermilion applied to Adam’s cheeks signify the awakening of desire at the moment when the Creator shows him the newly created Eve. Koerner is implicitly countering Falkenburg’s strong argument that what is enacted in paradise is an allegory of the marriage of Christ and the Church. (That Koerner chooses to engage Falkenburg only in passing is an opportunity missed.) Third, seeded throughout Koerner’s chapters on Bosch are truly marvelous observations about his distinctive paint handling, and how facture foregrounds the novelty and, therefore, the pridefulness of the artist in tandem with his human subjects. As one moves from the paradise panel to the hell panel of The Garden of Delights, for example, Bosch’s technique changes drastically – from the more traditional handling of the former, worked in minute brush strokes and transparent glazes, to an increasingly robust and simplified single layer of brushwork, where the paint surface mingles with visible underdrawing. This explicitness of painterly facture is thus proportional to the description of human vagrancy, and the painter’s ingenious manipulation of materials participates boldly in the allegorical effect he strives to produce. Koerner formulates both succinctly and elegantly this coincidence of manner and meaning: “Bosch thus binds painterly facture – how he actually makes the image – to the story the painting tells.” (219)

Walter S. Melion

Emory University

1. M. Heidegger, “The Age of the World Picture (1938),” in Off the Beaten Track, ed. and trans. J. Young and K. Haynes (Cambridge: 2002), 57-85; Koerner, Bosch & Bruegel, 279-280, 307.

2. Koerner briefly discusses the Seasons as quintessential examples of Bruegel’s ethnographic mode; see ibidem, 345-355. On Bruegel’s “grisailles”, see W.S. Melion, “Ego enim quasi obdormivi: Salvation and Blessed Sleep in Philip Galle’s Death of the Virgin after Pieter Bruegel,” Nederlands Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 47 (1996): 15-53; idem, Visual Exegesis and Pieter Bruegel’s Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery,” in Imago Exegetica: Visual Images as Exegetical Instruments, 1400-1700 [Intersections: Interdisciplinary Studies in Early Modern Culture 33], eds. W.S. Melion, J. Clifton, and M.Weemans (Leiden and Boston: 2014), 1-41; and “Signa Resurrectionis: Vision, Image, and Pictorial Proof in Pieter Bruegel’s Resurrection of circa 1562-1563”, in V.K. Robbins, W.S. Melion, and R.R. Jeal, eds., The Art of Visual Exegesis: Rhetoric, Texts, Images, eds. (Atlanta: 2017), 381-440. On the hermeneutical form, function, and argument of Bruegel’s Seasons of the Year, see B. Kaschek, Weltzeit und Endzeit: Die Monatsbilder Pieter Bruegels d. Ä (Munich: 2013).