This catalogue accompanied the exhibition Haute Lecture by Colard Mansion: Innovating Text and Image in Medieval Bruges, co-organized by Musea Brugge and Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge. Devoting an elaborate exhibition and extensive catalogue to Colard Mansion (active 1457-1484) is not an obvious choice as Mansion produced illuminated manuscripts, (illustrated) books, and objects at the crossroads of both genres, and the curators deserve praise for this admirable effort. For the first time in over five centuries, copies of all Mansion’s incunabula were brought together in their city of origin, accompanied by numerous illuminated manuscripts, prints, archival documents, paintings, and metalwork. International loans came from the Bibliothèque nationale de France and other European and American collections.

In the first pages of the book, the editors briefly introduce us to Colard Mansion, a versatile figure in the book trade of late-medieval Bruges. In this catalogue, nearly fifty authors from several disciplines – both esteemed specialists and junior scholars – present “the most up-to-date scholarship on the biography of Mansion and his substantial network, the gradual transition from manuscript to print, workshop practices and publishing strategies for the printer-publisher, late-medieval printmaking, and the impact of an impressive vernacular literary corpus” (p. 9). What follows are fourteen concise essays and an epilogue, alternating with entries on more than one hundred objects. The catalogue does not strictly follow the balanced, thematic order of the exhibition. As a result, the relationship between the essays and the consecutive entries is not always clear.

In the first essay, Ludo Vandamme discusses the little we know about Mansion’s life. He was active in Bruges from 1457 to 1484, but where he was born, where he grew up or where he went later on in his life is unknown. Peter Stabel then analyzes the urban economy of fifteenth-century Bruges. While it was, to a certain extent, a creative economy geared towards luxury products and art for an elite, international audience, manufacturers of fashion and durable consumer goods for the urban middle classes also did particularly good business. In one of the publication’s most refreshing contributions, Paul Trio reexamines Mansion’s relationship with the Guild of St. John the Evangelist, the Bruges guild of book producers and merchants. In contrast with some conceptions in the previous literature, he concludes that Mansion was doing well financially and that he was a prominent member of the guild in good standing. Renaud Adam explores the milieu of Bruges printers, with special attention to collaborations and workshop organization. Lotte Hellinga delves deeper into the relationship between Mansion and William Caxton, the English merchant who introduced printing with moveable type in Bruges in 1473 and left for Westminster three years later. Hellinga suggests that Mansion worked for Caxton before setting up his own shop in 1476.

The next handful of essays demonstrates how tradition and innovation came together in Mansion’s workshop. Nathalie Coilly deals with the incunabula he printed from 1476 to 1484, mainly in the French language. By using a specific font (bastarda), combining black and red ink, integrating manual rubrication and illumination, and printing on vellum, Mansion’s workshop explored various possibilities to produce books in the style of Burgundian luxury manuscripts. Evelien Hauwaerts discusses his activities as a producer of manuscripts. She reminds us that Mansion was active as a scribe, translator and manuscript seller before his activities as a printer, and that he kept producing high-quality manuscripts until the end of his known career. Till-Holger Borchert explores how Mansion used printmaking to illustrate some of his publications. His edition of De la ruyne des nobles hommes et femmes (a French translation of Boccaccio’s De casibus virorum illustrium) is one of the first to combine moveable letters with intaglio illustrations. The pasted-in engravings are exceptional because of their large dimensions and unusual subject, and they demonstrate how early printmakers found inspiration in illuminated manuscripts. Evelien de Wilde carefully zooms in on the content and production of Mansion’s Boccaccio. This milestone in his output contains nine engravings by an anonymous master (or masters?), but its layout stays close to the manuscript tradition. Mansion gradually refined this project. As early copies do not have sufficient space to fit the engravings, these were probably intended to be finished by hand with miniatures. Scot McKendrick and Lieve De Kesel discuss the French literary culture in the Burgundian Netherlands. By publishing various genres in French, the content of Mansion’s books also matched the manuscripts collected in aristocratic libraries.

Hanno Wijsman points out that while the book market was gradually shifting from manuscript to print, texts that were intended for the noble elite gradually reached a broader audience. With his innovative products, Mansion might have fallen between two stools. His printed works were possibly not luxurious enough to be fully embraced by the nobility, while the chosen texts and language were not ideal to find a broad audience in Flanders. Anna Gialdini and Ludo Vandamme approach Mansion’s output from the consumption side. By analyzing the preserved copies, they try to reconstruct their target audience and usage. In another contribution, Evelien Hauwaerts focuses on Mansion’s edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Illustrated with 34 woodcuts, this was the last book to come off Mansion’s press before he left Bruges in 1484. Jelle Haemers paints a picture of the political developments and conflicts of the time. It is possible that Mansion fled the city out of disagreement with the implemented policies, but since he had no political past, his motives might have been economical instead. In the epilogue, Hauwaerts evaluates the impact of Mansion’s oeuvre. The demand for luxury manuscripts and similar objects declined in this period as a result of the political situation – predominantly the diminished presence of the Burgundian court – and the changing interests of the market. Nonetheless, Mansion did well financially, probably in large part due to the patronage of powerful bibliophiles.

The book also includes over 80 catalogue entries on more than one hundred objects. However, some exhibited works are only included as additional images in the essays (figs. 24, 73, 197, 198). The entries include extensive information on the objects, their provenance and previous scholarship. Both texts and images are thoroughly analyzed to study the cultural and socioeconomic context in which Mansion operated. A selection suffices here to demonstrate the wealth of objects and the variety of questions asked about them. The majority of the selected works are incunabula published by Mansion. Complemented by publications by Caxton and other contemporaries, these books are analyzed variously: in terms of the papers and types (cat. nos. 28-29), rubrication and printing with red ink (cat. nos. 32-33), the illumination of books (cat. nos. 23, 36, 110), woodcut illustration (cat. nos. 37, 53, 103), and adaptations by readers and the target audience (cat. nos. 93, 95, 107). Crucial publications by Mansion are represented by several copies, such as his Boccaccio (cat. nos. 36, 56-60, 96-97). Manuscripts are also well represented and are approached from angles such as the authorship of the translations and illuminations (cat. nos. 1, 40, 77), the relationship with printed illustrations (cat. nos. 41-42, 54), bookbinding (cat. nos. 12, 16-17), and patronage (cat. nos. 6, 105).

Scholars of early Netherlandish printmaking will be delighted to see that the work of artists such as Master WA (or rather Master W with the House Mark) are discussed in relation to the court of Charles the Bold (cat. nos. 84-90) and to objects in other media, such as metalwork (cat. nos. 10-11) and architecture (cat. nos. 43-44). Evelien de Wilde also identifies one Vienna impression of Master FVB’s Judgment of Solomon as a new, third state (cat. no. 21), but direct connections with Mansion are never made. Archival documents relating to Mansion are also included. Perhaps most remarkable is the contract for an illuminated manuscript, signed by Mansion, that recently resurfaced and was acquired by the Openbare Bibliotheek Brugge (cat. no. 80). Several paintings, by artists such as Petrus Christus (cat. no. 99) and Hans Memling (cat. no. 100), illustrate the function of other objects and demonstrate how the organizers spared no effort or expense to include the broader context. The catalogue concludes with a reference list of Colard Mansion’s incunabula and several indices.

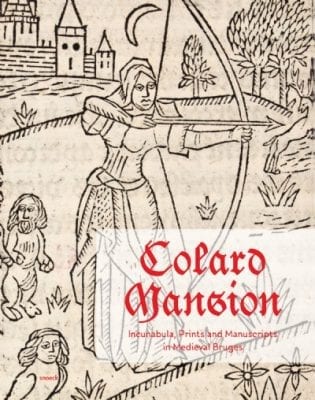

This beautifully produced catalogue is set in two specially designed fonts, inspired by Colard Mansion’s types, and contains over 200 color illustrations, although the organization of the images is not always clear. The many contributors provide numerous new insights into the life and work of Mansion and his contemporaries, but they sometimes formulate conflicting views, for example on Mansion’s financial situation and his relations with the guild (essays by Vandamme and Trio) and on aspects of the Boccaccio engravings (essays by Borchert and de Wilde). In addition, some repetition can be found in the book as a consequence of the large number of essays and entries. Nonetheless, the wealth of objects discussed and the variety of questions asked make it the most extensive publication on Mansion to date. It is the point of departure for any future research on this figure who stands at the crossroads of illumination and printing, tradition and innovation.

Jeroen Luyckx

KU Leuven