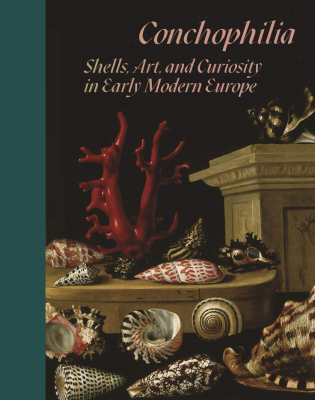

A very handsome book replete with full-color photographs, Conchophilia is a joy to read, as appealing and stimulating as the curiosities it considers. Comprising an introduction and six chapters, the book investigates collectible shells, their representations, and their diverse places in early-modern culture. In her introduction, “For the Love of Shells,” Anne Goldgar presents the neologism of the book’s title, “conchophilia,” which should now appropriately enter the discourse on the subject. It aligns with the Dutch term liefhebber – literally “lover,” but with connotations of the amateur, devotee, or connoisseur – which was, as Goldgar points out, often used in conjunction with delectables and collectibles, including art, poetry, flowers, and shells, the latter explicitly so in the name of the first Dutch shell-collecting club, “de Liefhebbers van Neptunus-Cabinet,” founded in Dordrecht in 1720. Despite the broad subtitle (Shells, Art, and Curiosity in Early Modern Europe), the focus is largely on the Netherlands and its global commercial and colonial enterprises. (The 2018 Renaissance Society of America annual meeting panels, from which the book directly derives, were called “Conchophilia: Shells as Exotica in the Early Modern Netherlands,” with a nearly identical line-up of contributors.) The Netherlands played a particularly significant part in the shell trade, and Dutch enthusiasm for collecting shells was unsurpassed.

Goldgar and the other contributors to the book treat this conchophilia as a broad cultural phenomenon. There is relatively little here on the scientific aspects of shells and their ecology, or, indeed, the history of a developing scientific understanding of them, because, as Goldgar points out, most of liefhebbers’ attention was given to shells’ aesthetics and cultural meanings. But there is much here on shells as objects, from the painstaking process of gathering them and preparing them for the international market, mostly by indigenous labor (treated especially in Claudia Swan’s chapter), to their appreciation as individual things of beauty and interest, appealing to both sight and touch, as well as their use in decorative schemes. The shells that were collected in Europe were simultaneously natural and artificial objects. The artifice was often extended by luxurious mounts and—one step removed from the objects themselves—description and depiction.

The book is divided into three sections of two chapters each. The first section, “Surface Matters,” attends most closely to the material qualities of shells. Claudia Swan, in “The Nature of Exotic Shells,” draws attention to the moeite en verdriet (trouble and tedium) involved in the labor-intensive process of preparing shells for export from their places of origin (and effectively “de-naturing” them), described at length by Georgius Rumphius – a long-time functionary in the Dutch East India Company (VOC), resident of the island of Ambon in what is now Indonesia, and one of the most important figures in Dutch conchophilia – in his D’Amboinsche rariteitkamer, first published posthumously in 1705. Swan notes also the sensual and even erotic qualities of shells – called “sensualities” (Sinnelickheden) in the 1628 sale of a Leiden collection – as they were marketed and represented in seventeenth-century painting. Those qualities are brought to the fore in Anna Grasskamp’s “Shells, Bodies, and the Collector’s Cabinet,” which brings considerable German material into the discussion. She explores correspondences between shells and human body parts – shapes, surfaces, terminology – and identifies the Kunstkammer as a potential “site of sexual knowledge and erotic fantasy,” implying perhaps an extreme form of conchophilia. Shells and (Asian) ceramics were associated in the early-modern period, and Grasskamp argues that European conchophilia, in its “sensual engagement with foreign surfaces . . . involved the objectification and fetishization of naked “foreign” bodies.”

In the second section, “Micro-Worlds of Thought,” the authors exemplify how to “think through” and “think with” shells. Marisa Anne Bass (“Shell Life, or the Unstill Life of Shells”) argues for the implied movement of shells in still life pictures, rejecting the simple identification of shells as symbols of the vanity or transience of earthly things in favor of their potential, whether represented in a painting or held in the hands of a collector, for activation or animation. In her “Thinking with Shells in Petronella Oortman’s Dollhouse,” Hanneke Grootenboer focuses on a cabinet holding a collection of tiny shells (actual naturalia rather than representations) – a detail of the famous Rijksmuseum dollhouse – in defining the ensemble as a denkbeeld (thought-image): a site of contemplation for Oortman, a kind of ego-document, a “model of intimacy that offers a figure of interiority,” rendered more poignant by its evocation of the deaths of two children and a husband.

The third section, “The Multiple Experienced,” begins with a chapter, Róisín Watson’s “Shells and Grottoes in Early Modern Germany,” that also identifies the use of shells for contemplation, taking us from the miniature configuration in Oortman’s dollhouse to a complex, all-encompassing decorative scheme in Duchess Magdalena Sibylla von Württemberg’s grotto in Stuttgart, which is no longer extant but known from engravings. Again death permeates the work, which, in this instance, is a space for the duchess to mourn her late husband and prepare for her own death, in contrast to the usual social functions of grottoes. The second chapter of this section and the final one in the book, Stephanie S. Dickey’s “Shells, Prints, and the Discerning Eye,” turns our attention most fully to collectors with a somewhat surprising point of departure: Rembrandt’s only printed still life, probably of an object in his own collection, The Shell (Conus marmoreus), an etching signed and dated 1650, known in three states. Her concern is with the etching’s status as a commodity, which leads to an extended discussion of the parallels between prints and shells in appraising desirability and market value. Both kinds of objects were collectible multiples with slight variations and were very often found in the same collections.

Dickey follows the network of collectors through the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth, from the Netherlands to England to France. All the chapters in the book are similarly expansive. Since this is a volume of case studies rather than a survey, some relevant subjects are naturally given little or no attention. But even if figures of great significance, such as Filippo Buonanni, are not the subject of any of the chapters as such, they run like threads through the entire volume, providing adequate context for the individual studies. The focus on Europe may have excluded an extended discussion of uses of mother-of-pearl (nacre) in, for example, enconchado of New Spain or Japanese inlay, but much of the value and appeal of the book, beyond the analysis of particular instances of conchophilia, lies in exemplifying diverse approaches to the subject that deepen our understanding of the cultural significance of shells. Cited several times in the volume is Philibert van Borsselen’s Strande (Beach) of 1611, a lengthy poem dedicated to a shell collector, in which he compares shells to paintings, ivory turnings, and porcelain, and we might add a persistent comparison to flowers, as well as other small items appreciable, collectible, and depictable for their interest and beauty. But this book postulates that there is something special about shells that differentiates them from such comparables. These mysterious objects meld, or oscillate between, surface and interior, nature and artifice, life and death. As Bass writes, they “are too restless to be held in place by symbolic meaning or fixed interpretations. They are, in art as in nature, the ultimate curiosities.”

James Clifton

Director, Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation

Curator, Renaissance and Baroque Painting, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston