When Swedish Ambassador Pieter Spiering agreed to pay young Gerrit Dou 500 guilders annually for the right of first refusal of the painter’s panels, the aristocrat effectively purchased social capital as a “skilled consumer.” Dou, in turn, bartered his way into an uncharted market landscape, one that he manipulated to become one of the most famous genre painters in Holland and beyond. Both collector and artist adapted to a new set of conditions that the Dutch economy brought to the seventeenth-century art market.

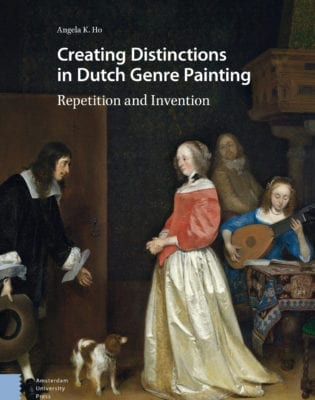

In Creating Distinctions in Dutch Genre Painting: Repetition and Invention, Angela K. Ho skillfully examines how creators and connoisseurs exploited an economic revolution. The period between 1648 and the end of the century was socially and economically uneven. For most of that era, the non-noble patrician class was eager to flaunt new wealth and a cultural connoisseurship that until then only existed in royal courts. Artists practiced a combination of aesthetic repetition and invention, enchanting collectors and competitors with unexpected twists on established themes. The way in which these two communities dialogued with themselves and to one another forms the foci of Ho’s forceful analysis. How did artists and collectors signal their skill to one another? How does an artist grab the attention of peers and clients with something old yet new at the same time?

The particular approach that Creating Distinctions takes toward the subject of genre paintings is enjoying a moment of its own. Genre paintings have been popular subjects of academic analysis since the nineteenth century. They have been scrutinized for various reasons that say as much about the era from which they are re-evaluated as they do about the paintings themselves. In the last fifteen years, historians have advanced Eddy de Jongh’s interdisciplinary cultural analysis of these pictures in new directions. One contribution to the conversation is Vermeer and the Masters of Genre Painting: Inspiration and Rivalry, the delightful catalogue that accompanied the 2017 exhibition of the same name organized jointly by the Louvre and the National Galleries of Ireland and Washington. As the existence of this catalogue indicates, we continue to move beyond the canvas or panel to think deeply about their relationship to topics like consumer psychology. Ho’s book gives this conversation an energetic push.

Chapter One is a methodical invitation to both the art history student and the expert. Ho charts the network she will be dialoging with throughout the book: her academic predecessors, seventeenth-century art collectors, and the specific concepts she will use to frame the actors in the Dutch art market. The most important concept she extends to the reader is Karel van Mander’s term liefhebber or “lover of paintings” (39). In some elevated social circles, it was not enough to be an art collector. To those who did not just buy paintings to delight and entertain but intellectualized the visual arts as a complex human phenomenon to devour, Van Mander awarded the term liefhebber. These committed people caught the nuance and deep references that eluded the casual art collector. They derived as much satisfaction from the pictures as they did by signaling to peers the depth of their cultural savvy. They formed the audience for three artists in Ho’s analysis: Gerrit Dou, Gerard ter Borch, and Frans van Mieris.

Gerrit Dou’s niche paintings are a latticework of established iconography and nods to mentors like Rembrandt, but they are also an affirmation of their maker’s skill as a businessman and strategic self-promoter. Dou’s use of the niche picture format, a trademark motif he settled on around 1650, was repeated across more than forty pictures. Ho charts other features that make repeat appearances in his works, such as a quotation of François Duquesnoy’s bas-relief “Bacchanal.” Dou’s repetition of motifs was more than a time-saving measure for an artist who, according to Joachim von Sandrart, was a slow and meticulous painter. Ho argues that by creating a picture window populated with a mix of established art tropes and allusions to contemporary culture, Dou created reflexive paintings whose self-awareness was irresistible to liefhebbers. He created for himself a distinctiveness that made him stand out in a crowded market.

Few artists captured the ethos of refinement with as much subtle shimmer as Gerard Ter Borch. His talent for tapping into the material desires of the post-treaty collector makes his work one of the most enthralling windows available into the aspirational self-image of the aristocratic class. Ho’s third chapter is her strongest and most delightful. She is less concerned about what Ter Borch’s paintings mean and is more interested in how the artist wielded ambiguity like any other tool in his studio. Repetition is critical to Ter Borch’s innovation. He delivers themes that audiences recognize: brothels, threats to physical and domestic purity, and displays of fashionable courtly etiquette. Ho argues that Ter Borch challenged liefhebbers’ expectations of trusted tropes by placing stock figures into scenes where they otherwise would not appear. For example, in Gallant Conversation (Pl. 9), Ter Borch included a male sitter whose relaxed posture is traditionally seen in portraits of powerful merchants lounging in private studies and kamers. Ter Borch defied expectations by mixing stock figures and settings and producing unlikely combinations that offer liefhebbers a novel product that goads their attention and invites their curiosity. And oh, that satin dress!

Chapter 4 evaluates how artists and art markets responded to Holland’s economic contraction at the end of the century. For many, the art party that roiled throughout the first half of the century had come to an end. Collectors drifted away from the art market, leaving only the ultra-wealthy to grab up the remnants. Liefhebbers were less likely to purchase works by living artists, opting instead for the prestige of the old masters. Ho praises Van Mieris as a painter who devised a stratagem to compete with established masters: imitate them without looking too obvious about it. The artist looked to Dou and Ter Borch, and mimicked (rapen) the general spirit of what made those pictures distinctive. The result was a stylized take on what liefhebbers already knew they loved.

Like the painters she considers, Ho signals her own skill as a steward of Dutch genre painting. She brings a wealth of research to her analysis, mixing established academic theory with enthusiastic reinterpretations of primary sources that we thought we knew. The result is a reflexive work that draws our attention to the potential of the art history discipline as it considers the art market of the past.

Ryan Gurney

University of California, Irvine