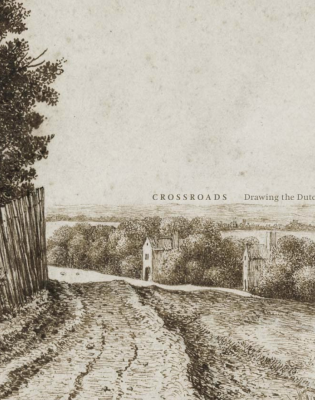

Between the late sixteenth and early eighteenth century, Dutch artists produced a staggering number of landscape drawings. This richly illustrated catalogue, published in the wake of an exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums (May 21 – August 14, 2022), explores this surge in landscape productivity through a selection of 90 works – primarily drawings, but also prints, a hand-colored map, and two albums. Their dates of creation span the long seventeenth century, beginning with Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Wooded Landscape with a Distant View toward the Sea (1554) [Fig. A] and ending with Cornelis Troost’s Park Scene (1740s) [Fig. U]. The exhibition’s artworks come from the combined holdings of the Harvard Art Museums and the Maida and George Abrams Collection. The Abrams’ 2017 promised gift of more than three-hundred drawings to Harvard’s Museum not only inspired the present exhibition, but also transformed Harvard’s into the most encyclopedic collection of Dutch drawings in North America. Like the Abrams’ bequest, this catalogue comes as a gift for devotees of Dutch landscape drawings – expanding the possibilities for understanding this wealth of graphic material.

The exhibition’s curators, Joanna Sheers Seidenstein and Susan Anderson, are not shy about announcing the show’s significant place at a crossroads in the historiography of landscape studies and museums. Both have been called upon, they remind us, to shift art historical narratives towards more inclusive histories. Likewise, Museum Director Martha Tedeschi is careful to acknowledge in the catalogue’s foreword the ways that present-day realities – immigration, the rise of digital technologies, and the COVID-19 pandemic inflect our relationship to the environment. The exhibition, therefore, welcomes the range of responses that the landscape’s image might evoke for present-day viewers, from its natural beauty to environmental decay, socioeconomic disparity, and the legacies of colonialism.

In her introduction to the catalogue, Susan Anderson contextualizes watershed landscape productivity against the historical backdrop of the Dutch Republic’s global ambitions, local political unrest, urban expansion, and massive land reclamation projects. The landscape that Dutch artists pictured, she shows, was not a stable entity, but rather one that was in a state of production and flux – cartographically, infrastructurally, ecologically, and geopolitically. In doing so, she frames the exhibition’s aim: to expand the places and associations with which Dutch landscape drawings are typically associated.

The diversity of the drawings in the exhibition, which range in format, execution, and size reveal the varied techniques with which artists shaped their relationship to the land. The artworks also visualize the contours of a diverse local topography. Cornelis Claesz. Van Wieringen’s Coastal View with Ships, Crag with Castle, and Bridge (c. 1600-10) [Fig. 8] shows a rocky coastline, Jan Lievens’s Forest Landscape with a Pond (c. 1650-70) [Fig. Q] situates the viewer at the edge of a dense forest, and Adriaen van de Venne’s Spring (1622) [Fig. G] shows a fantastic castle in the distance. We also see remote locales: Brazil through the eyes of Jan van Broysterhuysen and Frans Post (Fig. 11), France as seen by Lambert Doomer (Fig. 12), and Scandinavia per Allart van Everdingen (Fig. S). Collectively, such images reveal how artists creatively manipulated identifiable sites and recognizable topography, often confusing the boundary between what was produced naer het leven and uyt den gheest.

Seidenstein’s essay, “Shifting Terrain, Environmental Change, Global Expansion, and the Drawn Landscape,” re-interprets Dutch landscape drawings with a heightened attention to the social inequities that environmental uncertainties presented to the Low Countries’ inhabitants. For Seidenstein, the sheep that graze at middle ground in Cornelis Vroom’s drawing, Landscape with a Road and Fence of 1631 (the catalogue’s cover image; Fig. 1), evoke the impoverished, war-torn landscape on the outskirts of Holland’s cities and the challenges that they posed to subsistence farmers. Similarly, the juxtaposition of different classes in Hendrick Avercamp’s winter landscapes vividly displays the realities of economic disparity (the well-heeled are pulled on horse-drawn sleds, while others trudge through winter’s cold in search of food). Seidenstein investigates the motivations for creating drawings of the local landscape. An urban clientele, Seidenstein supposes, may have desired images that not only evoked the leisure of the countryside or the value of their investments, but also ones that expressed the landscape’s vulnerability. This interesting claim merits further investigation. Today, we see landowners making efforts to conceal, not expose, the vulnerability of their property to natural threats such as forest fire, drought, and sea-level rise. How and why were seventeenth-century Dutch sensibilities towards the land calibrated differently?

Joseph Koerner’s essay, “Drawings as Friends” also expands public audience’s understanding of, and appreciation for, landscape drawings by illuminating the ways that such collectibles were used. While occasionally framed and displayed on the wall (as was Avercamp’s Winter Landscape, which remains in its seventeenth-century frame), drawings were typically compiled as loose sheets into albums or preserved in alba amicorum. The exhibition’s display of the so-called Abrams Album (c. 1634-45), an oblong leather-bound book containing 41 drawings on vellum sheets by 27 artists who were active in Delft, vividly materializes the tactile and interactive nature of such an album for its owner. Most of the album’s drawings, which vary in subject matter, are signed, finished works of art and display each artist’s creative and sometimes competitive or playful response to the task of filling their assigned page: Pieter de Blot’s Seated Smoker Holding Tongs (Fig. 6) requires the viewer to rotate the album 90 degrees to properly see its humorous subject; Francois van Knibbergen’s Wooded Landscape is rendered with an incredible faintness of line (Fig. 7). As with all the drawings in the exhibition, the post-card size sheets reward careful study – an indication of their importance both to their maker and to their likely original owner, Pieter Spiering, as original, one-of-a-kind mementos. With its oblong shape, the exhibition catalogue also declares its ambition to be something of an album amicorum, constellating ideas about the landscape through a variety of voices and images.

While the exhibition’s curators clearly made efforts to meet the present moment’s attention to inclusivity, they missed a chance to recognize Dutch female artists’ important contributions to its theme. The meticulous studies of flowers, plants and animals by Rachel Ruysch, Clara Peeters, and Maria Sibylla Merian (who traveled as far as Surinam in her quest for exotic specimens), surely constitute an important part of the story here. Yet, they were not represented in the show. Their absence raises some crucial questions. Who has creative access to the landscape? Who can be an environmentalist? What places and environments are not represented in the body of drawings that are preserved and displayed in our museums?

So, what can the Dutch and their compulsive graphic attention to the landscape tell us in our current moment of climate change and ecological devastation? Perhaps, as they did in the seventeenth-century, the images remind present-day viewers to treasure environments that may soon disappear.

Rachel Kase

Boston University