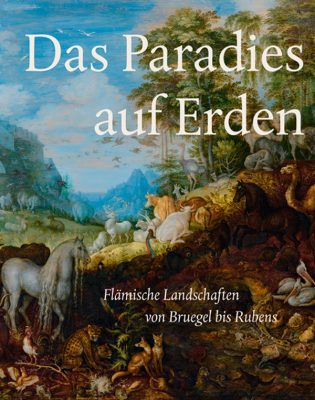

The Gemäldegalerie in Dresden has a rich collection of Flemish landscape paintings of the highest quality. Of the approximately 150 works from the sixteenth to the early eighteenth century, roughly 105 have been extensively researched since 2011, inspiring this exhibition and announcing the future three-volume Bestandskatalog of the museum’s Flemish paintings. The hefty exhibition catalogue, fittingly designed in landscape format, contains eight essays discussing Flemish landscape painting from different viewpoints, independent of the chronologically arranged catalogue.

Manfred Sellink (“Die Landschaft in der Kunst der südlichen Niederlande bis 1600”) reminds the reader that Bartolomeo Fazio mentions shortly before 1457 besides the Italians Gentile da Fabriano and Pisanello the Netherlandish artists Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden as landscape specialists. However, the Italians’ landscape backgrounds are at best accessories to religious subjects. The Flemish dominance in landscape painting becomes evident in Jan van Eyck’s St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata of 1432 in Turin (Galleria Sabauda). Here the balance between large foreground figures and the landscape is a feature not found that early in the works of the two Italians. Sellink then introduces subsequent generations of artists, starting with Joachim Patinir as one of the founders of the autonomous landscape, noting the lack of attention paid so far to the central role played by miniatures, as exquisitely demonstrated with works from the Dresden collection (cat. nos. 2, 3), or the landscape backgrounds in tapestries, still terra incognita in present-day research. Despite the paucity of and, consequently, connoisseurship in early drawings, Sellink agrees with the hypothesis that the drawings by the Master of the Dresden Wilhelm von Maleval Drawing originate around 1500 (18), close to Patinir’s time: the first autonomous landscape compositions in drawing (cat. nos. 7-9). The discussion continues with Hieronymus Cock’s Views of Roman Ruins, the “Small Landscapes” series, and with hunting scenes and cartography – all central to the development of the autonomous landscape.

With Van Mander’s praise of the beauty of landscape pictures achieved through copia et varietas, abundance and variety, and his accolade of Bruegel and Coninxloo, we reach the seventeenth century, thus bypassing, as noted by Sellink, the important representatives of the new genre, such as Cornelis van Dalem, the reproductive prints after Frans Floris and above all Marten de Vos whose Antwerp publishers especially supported their landscapes (not to forget the art dealer Bartholomäus Momper, father of Joos). At the end of his survey of one hundred years of landscape painting, Sellink emphasizes the influence of Venice and the artists returning from there, such as Peter Paul Rubens.

Following Sellink’s reference to oltramontani returning from Italy, Nils Büttner (“Landschaft, Welt- und Sinnbilder”) cites the Cologne publisher Georg Braun who in 1581 characterized his vedute as Erinnerungsbilder (memory images). It was not the individual physiognomy of a landscape but the specific characteristics of a region that defined his chorographiae, adding another part of the puzzle to the origin of the genre. Büttner further refers to images of battles and sovereignties, to parks and gardens, contributing to the imperial habitus and pictorial propaganda of the archdukes. Now, around 1600, images of experienced or imaginary locations become part of the repertoire as emotionally palpable expressions of former world views and multifaceted emblems. Joos de Momper, Jan Brueghel and Peter Paul Rubens avail themselves of this new dimension of the genre.

Uta Neidhardt (“Von Paradiesen und Höllen – fantastische Landschaftsmalerei in unruhigen Zeiten”) investigates the literary sources of paradise and hell, two poles exemplified in Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights: Paradise, based on the Bible, at the left; Hell, based on the Visions of the Knight Tondal, at the right; at the centre the sins of the flesh. Neidhardt states that the two scenes, although contrasting, should be seen simultaneously, while his followers separate them into autonomous images of hell and conflagration, such as those by Jan Mandijn and Pieter Huys, as well as Pieter Bruegel’s Dulle Griet, and of paradise, such as those by Roelant Savery and Jan Brueghel. With the help of scientific, trustworthy encyclopedias of animals of the world, published in Antwerp, Savery’s and Brueghel’s paradise landscapes superseded Bosch’s and his immediate followers’ fantastic creatures.

Stefan Bartilla (“Landschaft und Wildnis um 1600”) also sees the century of discovery and curiosity as impetus for the new landscape category devoted to the study naer het leven. His essay follows the tradition from the biblical definition of nature to the new category in which natural scenery is the significant visual motif. Thus the perception of desert and wilderness does not correspond to our knowledge of these uninhabitable places today but to uncultivated, bleak and isolated nature. Hermits live in dark forests or remote mountains that function as metaphors for the biblical desert. The use of two or more viewing angles, changing perspectives, varying heights of the horizon and different lighting sources was perceived as realistic in seventeenth-century landscape representations.

This phenomenon is famously explained by Goethe to his friend Johann Peter Eckermann who observed, apparently in front of Schelte à Bolswert’s print after Rubens’s Return from the Harvest (cat. no. 121), that the figures and trees cast shadows in different directions, whereupon the great German responded that it is the master’s genius to surpass nature by using two contradictory light sources while at the same time creating the impression of a realistic image of nature: “Ein so schönes Bild ist nie in der Natur gesehen worden.” (“So perfect a picture has never been seen in nature.”) (1827) The quote introduces Nico Van Hout’s essay who then presents a survey of Rubens’s landscapes including engravings after them. According to Constantijn Huygens Rubens purchased an estate near the village of Eekeren in 1627 in order to escape the plague epidemic in Antwerp and to paint landscapes. In the early seventeenth century the real surroundings increasingly gain importance for artists, not only for Rubens but landscape painters generally.

Hildegard Van de Velde documents the collecting of landscapes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In the sixteenth century it was the merchant Lucas Rem in Augsburg, Cardinal Domenico Grimani in Venice and the Spanish diplomat Diego de Guevara who acquired landscapes by Patinir whereas the art-loving Margaret of Austria owned none of his paintings. At the Brussels court in the early seventeenth century Albrecht and Isabella especially supported Denis van Alsloot, Jan Brueghel I and Rubens as court painters while Pieter Snayers and Joos de Momper executed commissions for them (Momper had unsuccessfully applied for the court position). Collections in Antwerp document an enormous increase in landscapes by Brueghel, Coninxloo, Momper, Jan Wildens and Sebastiaan Vrancx.

Konstanze Krüger analyses the underdrawings in Flemish landscapes in Dresden, focusing on two paintings each by Herri met de Bles and Hans Bol, as well as works by Roelant Savery and Alexander Keirincx. The always individually distinct underdrawings revealed by infrared reflectography contribute greatly to questions of attribution

In the final essay Christoph Schölzel discusses the surprising discovery that the Dresden Landscape with the Judgement of Midas (cat. no. 58) is signed by Gillis van Coninxloo for the panoramic landscape as well as by Karel van Mander for the figures. Moreover, it is dated 1598 and not 1588 as previously assumed, thus prompting us to reconsider Coninxloo’s early work.

Following the exhibition in Dresden, a number of the exhibits went to the Rockoxhuis in Antwerp (March 24 – June 2, 2017), accompanied by a new publication with some additional essays.

Ursula Härting

Hamm (Germany)

Translated by Kristin Belkin