Jean-Baptiste Descamps was born in 1715 in Dunkirk, formerly a Flemish city which in 1662 had become annexed by France. He sought a profession as a painter and clearly wanted to orient himself towards the artistic tradition of the Southern Netherlands. Thus in 1725/30 he stayed in Antwerp, studying there at the renowned art academy. From c. 1738 onward he is mentioned in Paris, where he had found a job as drawing master at the Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture, which brought him into close contact with established painters as Nicolas de Largillière and Nicolas Lancret. Slightly later he moved to England in order to assist Jean-Baptiste van Loo. After these ‘Wanderjahre’ Descamps established himself at Rouen, to stay there until his death in 1791. His workshop there soon became an important drawing school, to become promoted in 1749 to a true Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture, an institution which Descamps continued to manage in an energetic way until his death. However, it is clear that Descamps subordinated his pictorial creativity to what he considered his personal pedagogic and art theoretical vocation. And in this context we should understand his two most important publications. The four volumes of La vie des peintres flamands, allemands et hollandois appeared between 1753 and 1763. And six years later Descamps published his Voyage pittoresque de la Flandre et du Brabant.

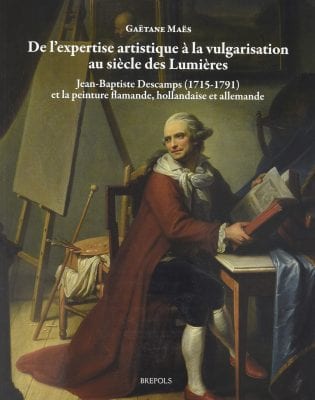

For the first time, the importance of these two books is explained in detail in the monograph by Gaëtane Maës under review here. Mme Maës, who is a member of the staff of the Institut de recherches historiques du Septentrion of the University of Lille, has published extensively on Descamps and the art theoretical discours of his time, recently having successfully presented her monograph as a Thèse d’Habilitation. In the first place, this book is a sound historical study based on numerous hitherto unpublished written sources, especially the detailed correspondence between Descamps and his contemporary colleagues. This very useful and informative material is published in extenso in the bulky Annexes at the end of the book.

The importance of the Vie des peintres lies in the very fact that this book brought to the French-speaking world information on painters from the Low Countries contained in collections by Van Mander, De Bie, Houbraken and Campo Weyerman hitherto available only to readers of Dutch. The moment at which Descamps brought his collection of biographies to the printer could hardly have been more propitious. Since the beginning of the eighteenth century Paris had become dominating as a centre of trading and collecting Dutch and Flemish painting. It is thus no exaggeration to state, as does Mme Maës, that Descamps, when drawing up his plan to publish his Vie des peintres, was guided as much by mercantile as by pedagogic motives. It is striking that in this book Descamps especially accentuates the mimetic realism as the highest quality of the northern masters and in doing so he was certainly voicing the artistic taste of mid-eighteenth-century Paris.

With his Voyage pittoresque Descamps aimed at giving the rich art treasures that could be seen in the Southern Netherlands their place in the travel program of the Grand Tour which from the later seventeenth century onward had become an important component of the Bildung of the young European élite, initially being focused especially on Italy. It was Descamps’s sincere belief that Flemish painting could best be admired in its still largely existing original ambiente. His Voyage pittoresque, in fact one of the eldest known traveler guides through the Southern Netherlands, became very successful from the outset. This also explains why the book became soon pirated. Also in these descriptions of the innumerable art works to be seen in the churches and other public places in Brabant and Flanders Descamps’s criteria of evaluation express his and his contemporaries’ admiration for Netherlandish art’s unsurpassable illusionistic realism in expression and detail. This also brings Descamps to a genuine admiration for the paintings of Jan van Eyck and Hans Memling. Foreshadowing the Baedeker and the Guide Michelin, Descamps distinguished clearly between works of greater and lesser importance, mainly through the use of asterisks.

It became history’s tragedy that this detailed and insightful guide through the art curiosities of the Southern Netherlands, which at that moment were still largely intact, would prove such a useful help when a few years after the publication of the book, the great dismantlement of the country’s art patrimony began, first with the public sale of the art treasures of the Jesuit churches (1777) and the convents of the contemplative orders (1785). But the book would especially demonstrate its unintended usefulness as a guide for the well instructed commissaires of the French Republic, when in 1794 they transported to Paris the most important part of the paintings that by then were still decorating the churches in the Southern Netherlands, in order to enrich the Muséum which was then being organized in the Louvre. In this context, I am wondering whether it might not be advisable to bring out a detailed and critical edition of this invaluable source of information, in the form of a fully illustrated catalogue raisonné of all the still extant paintings discussed by Descamps. This would also be an ideal opportunity to correct a number of attribution errors.

Needless to say, the importance of Gaëtane Maes’s in-depth study of Descamps’s two major titles in the early historiography of Netherlandish, and especially Flemish art, can hardly be overestimated.

Hans Vlieghe

Centrum Rubenianum, Antwerp