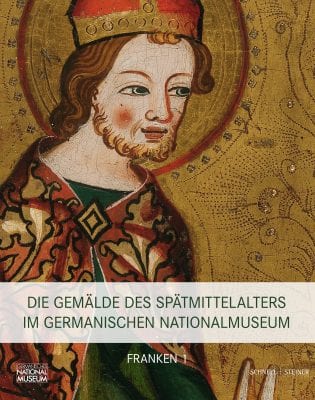

The Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg possesses around 250 German and Austrian paintings from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Most pictures are by now anonymous masters who are, not surprisingly, little known, even to many specialists. The broader history of pre-1500 painting in the German-speaking lands remains incompletely explained and largely regionally surveyed. Alfred Stange’s Deutsche Malerei der Gotik (1934–61, 11 volumes) has never achieved the influence of Max J. Friedländer’s Die altniederländische Malerei (1924–37; English edition – Early Netherlandish Painting, 1967–76, 15 volumes). G. Ulrich Grossmann, the museum’s former general director until 2019, remarks in his foreword (p. 15) that the lack of research during the decades immediately following World War II may have resulted from the past ideological misuse of German Gothic art. Fortunately, more recently, museums in Basel, Berlin, Cologne, Frankfurt, and Kassel, among others, have published excellent collection catalogues, increasingly informed by technological tools.

In 2013, Daniel Hess, formerly chief curator of paintings and now the museum’s new director, and his colleagues initiated an ambitious project to study its pictures from Nuremberg and Franconia, as the first of a planned series of catalogues on its extensive collection of pre-1500 paintings. They collaborated closely with the museum’s Institut für Kunsttechnik und Konservierung, headed by Oliver Mack. The 70 entries, ordered chronologically, are thorough; for example, number 43 on the St. Veit Retable is 60 pages long. Each entry provides basic information: attribution, date, materials, scale, and owner; detailed description; state of preservation; technological analysis; provenance and history of the picture; discussion of art historical issues; archival records and other documentation; and bibliography.

Since its founding in 1852, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum has served as a repository for various church, civic, and private collections. The museum actually owns only 13 of the catalogued pictures. Others are long-term loans from the Bavarian state, the city, local churches, and private collections (7). Together, these works make an impressive whole concerning the development of painting, especially in Nuremberg, since the 1340s. Most of the paintings once adorned local churches, including the convents of St. Klara and St. Katharina. Many are wing and predella fragments of altarpieces dismantled in the decades following secularization in 1802/03. These paintings functioned formerly as altars, epitaphs, votives, reliquaries, house altars, Rathaus justice panel, portraits, and a sliding frame cover for a portrait. While most of the masters worked in Nuremberg, several were active in Bamberg and Rothenburg.

The catalogue opens with an excellent introduction (pp. 19–37) by Katja von Baum, Judith Hentschel, Daniel Hess, and Dagmar Hirschfelder. They trace the history of exhibiting late Gothic paintings in Nuremberg, beginning around 1810, when several local monasteries were razed. The fate of some pictures was entwined with that of Nuremberg and Franconia, which were absorbed into the expanded kingdom of Bavaria in 1806. The Burggalerie opened in 1810, though many early pictures were moved into the imperial, now royal, castle when King Ludwig I visited in 1833. Paintings first entered the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in 1874 and 1880–82. The museum’s collection has grown steadily, and its most recent purchase of a Franconian picture occurred in 2013.

The authors survey various historical texts and early visual records of local buildings for information about some works of art and their original contexts. They summarize scholarship on the history of Nuremberg and Franconian pre-1500 paintings beginning with Henry Thode (1891), through the museum’s 1931 exhibition, Nürnberger Malerei 1350–1500, and finally the investigations of Peter Strieder and Kurt Löcher, past paintings curators at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, and, more recently, Robert Suckale’s magisterial Die Erneuerung der Malkunst vor Dürer (2009).

As the 70 paintings, which comprise 138 individual panels, were examined in the conservation lab, the researchers were able to assess the current state of each picture and to detect valuable information about past conservation. Many paintings were in poor condition after secularization. After early restoration campaigns, from about 1882 to 1894, paintings were sent to the Alte Pinakothek in Munich for conservation. The Germanisches Nationalmuseum hired its first restorer in 1920. This catalogue’s technical reports are often quite lengthy, and the museum has also created a related website (https://tafelmalerei.gnm.de).

The final section of the introduction addresses findings. For example, fragments of three separate altars (cat. nos. 2–4), made between 1360 and 1370 for the local convent of St. Klara, are products of the same Nuremberg workshop and provide useful information about the iconographic programs and liturgical needs of the Franciscan nuns. Related panels now in other collections are included in the reconstructions of individual retables. Fifteen pictures (cat. nos. 5–19) permit a clearer understanding of the evolution of Nuremberg painting during the first half of the fifteenth century. Six wing fragments of the former high altar of the Frauenkirche (cat. no. 5), dating around 1400/10, reveal the influence of the Weichenstil (soft style) out of Bohemia. The durability of the International Style, even in its late phase, is still evident in the workshops of the Master of the Deocarus Altar (1430s; cat. nos. 8–12) and the Master of the Tucher Altar (1440s; cat. nos. 15–17).

The character of Nuremberg and Franconian painting changes during the second half of the fifteenth century. Beginning with Hans Pleydenwurff (active c. 1440–72; cat. nos. 24–32), who worked in Bamberg before moving to Nuremberg in 1457, artists display their growing familiarity with Netherlandish paintings, especially those by Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, and Dirk Bouts. Pleydenwurff’s figures are highly three-dimensional, while the striking naturalism in the landscape and clothing often pair with a more traditional, patterned, gold sky. Particularly impressive is Pleydenwurff’s portrait of Georg Graf von Löwenstein, a canon of Bamberg cathedral (c. 1456; cat. no. 24), which closely recalls the format and material details of Van der Weyden’s devotional diptychs. The pendant Man of Sorrows, now in Basel, is attributed to Pleydenwurff’s workshop. The catalogue provides detailed examination of paintings by Pleydenwurff and his followers (pp. 337–464). Their investigations, especially based on technical aspects of the workshop’s production, nicely complement Robert Suckale’s research on the artist and Stephanie Buck and Guido Messling’s insightful study of the large corpus of drawings by Pleydenwurff and his circle in Zeichnen vor Dürer. Die Zeichnungen des 14. und 15. Jahrhunderts in der Universitätsbibliothek Erlangen (2009).

The Germanisches Nationalmuseum’s collection is especially strong in paintings done during the last quarter of the fifteenth century. Nine entries (cat. nos. 33–41) discuss pictures by Michael Wolgemut (c. 1434/37–1519), who married Pleydenwurff’s widow in 1472, and the large workshop that he took over. Albrecht Dürer, Wolgemut’s pupil, is represented by the portrait of his mother Barbara (1490; cat. no. 42). The St. Veit Retable (1487; cat. no. 43), originally in the Augustinian Hermits church of St. Veit in Nuremberg, is among the largest and most impressive altarpieces now in the museum. Based on stylistic similarities with drawings (figs. 43.60–43.63) in the Universitätsbibliothek Erlangen, this former high altar is now attributed to Hans Traut, a Speyer artist, active in Nuremberg between 1477 and 1516, and his workshop. This polyptych and a group of five related pictures (cat. nos. 44–48) display highly expressive figures and sophisticated treatment of naturalistic landscapes.

Even though most of the catalogue covers masters active in Nuremberg, four paintings link to Bamberg painters Wolfgang Katzheimer (act. 1465–1508; cat. nos. 49–50) and Master L.Cz. (active last quarter of the fifteenth century; cat. nos. 51–52), better known as an engraver. Martin Schwarz (active 1485–1511; cat. no. 55), a Franciscan monk in Rothenburg who collaborated with sculptor Tilman Riemenschneider, authored the surviving wings of a Mary altarpiece (c. 1485/90; cat. no. 55) for the Dominican convent in that town. Several of his scenes reveal influence from Martin Schongauer’s engravings.

Independent portraits before 1500 were relatively rare in German art. The catalogue includes the likenesses of Dürer’s mother and six men. Jakob Elsner’s Jörg Kötzler (1499; cat. no. 53) is the finest portrait by this Nuremberg painter and manuscript illuminator. Its inscription on the panel’s reverse is readable now through infrared examination. Kötzler’s first person text reveals: his identity, his birth date and current age (28), his parents’ names, the date of the inscription, the artist’s name, and even the painting’s cost.

Daniel Hess and his colleagues are to be congratulated. This massive catalogue makes an invaluable contribution to our understanding of early German, specifically Franconian, painting. It will long remain a model of the fruitful collaboration of art historians and conservators.

Jeffrey Chipps Smith

University of Texas, Austin