In fifteenth-century Leuven, Dieric Bouts (c. 1410/1420-1475) produced high-quality panel paintings that have remained somewhat eclipsed by the oeuvres of figures such as Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden. M Leuven sought to redress this by organizing an extensive exhibition in the city where the Netherlandish master lived and worked. It took a radical approach by juxtaposing a number of his key works, including several impressive loans, with examples of today’s visual culture, but the show raised more questions than it provided in-depth answers or enlightening insights.

In the past, M Leuven has staged accomplished exhibitions both on individual early Netherlandish artists (e.g. Rogier van der Weyden 1400-1464: Master of Passions, 2009, curated by Jan Van der Stock and Lorne Campbell) and on themes explored through transhistorical confrontations (e.g. Alabaster, 2022-2023, curated by Marjan Debaene and Sophie Jugie). Now the museum appears to have combined these two approaches to explore the oeuvre of Bouts. The exhibition was divided into seven themes. While these themes were explained in wall texts, the individual object labels contained no extra information, and the audio guide only elaborated on selected objects.

A masterpiece, Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus with Saints Jerome and Bernard (Leuven, Saint Peter’s Church), opened the exhibition. This triptych immediately set the tone for the refined paintings that left Bouts’s workshop, characterized by careful compositions, lifelike figures, and vibrant colors. Few biographical details are known about Bouts, but the first section, “Context,” explored the milieu in which he operated. After the founding of its university in 1425, Leuven became a cultural and intellectual center. Numerous libraries, especially that of Park Abbey, housed manuscripts with antique and humanist texts and made sure that the spirit of the Renaissance dwelled through the city. Bouts’s patrons, who included the Church, the city council, and the wealthy bourgeoisie, were represented by the Portrait of a Man (Jan van Winckele?) (London, National Gallery) and the metalpoint drawing Portrait of a Young Man (Northampton, MA, Smith College of Art Museum). According to the wall text, these remarkable works were confronted with recent cartoons and advertisements to demonstrate that, “just like Dieric Bouts more than 500 years ago, graphic designers, cartoonists and advertisement designers create images that fit perfectly into their contemporary context.” Contemporary images freely available to a large audience were equated here with high-quality works of art from five centuries ago that were only available for the lucky few. One wondered what the added value was of displaying a national railway advertisement for Christmas shopping on a large electronic screen in the same room as the small, refined, and light-sensitive paintings and drawings.

The next section, “Christ,” focused on the Vera Icon. Influenced by the Modern Devotion, personal prayer and meditation became increasingly important in the fifteenth century, creating a demand for small paintings of the true image of Christ. Bouts’s Vera Icon (Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen) and works by his son Albrecht such as the Triptych with Ecce Homo and Mater Dolorosa (Aachen, Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum) and Saint John’s Head on a Platter (Antwerp, Phoebus Foundation) were alternated with photographs of exceptional athletes like the cyclist Eddy Merckx and the basketball player Kobe Bryant. This juxtaposition attempted to demonstrate that modern athletes are also seen as demigods, worshipped for their suffering and remarkable achievements. Soccer player Diego Maradona, who is actually venerated today at various shrines in Naples, was overlooked.

The next room revolved around “Mary.” Indeed, imagery of the Virgin was highly popular, and the wall text correctly noted that “common folk could only afford a humble prayer card, while affluent citizens commissioned paintings from artists like Dieric Bouts.” Examples of these early cheap images were not included in the show; instead, photos and videos of Lady Gaga and Beyoncé featured, since “Mary was in many ways the pop star of the fifteenth century.” Although these recording artists sometimes refer to the Virgin Mary in their imagery or performances, they mainly draw large audiences for their individual accomplishments, while Mary was revered as the ultimate intercessor and remains a Christian symbol of motherly love. Highlights here included the Notre-Dame de Grâce (Cambrai Cathedral), a fourteenth-century Italian Madonna once thought to be painted by Saint Luke himself; Bouts’s Virgin and Child within a Stone Niche (Paris, Louvre) and Saint Luke Drawing the Virgin and Child (Barnard Castle, Bowes Museum); and Albrecht Bouts’s Veneration of the Virgin by Saint Joseph (private collection).

“Landscapes” explored how Bouts constructed imaginary landscapes for his biblical paintings such as the Lamentation of Christ (Paris, Louvre) and the fantastic triptych wings of The Blessed on their Way to Heaven and The Fall of the Damned (Lille, Palais des Beaux-Arts). The wonderful Triptych with the Martyrdom of Saint Hippolytus by Bouts and Hugo van der Goes (Bruges, Saint Salvator’s Cathedral) was also on display here. These works were displayed alongside videos, design drawings, and reproductions from the Star Wars films. Surely, there are some parallels between these clearly fictional yet convincing settings, but the power of saints and the idea of heaven and hell must have been very present in the daily life of fifteenth-century Christians and thus cannot be equated directly with recent science fiction films made purely for entertainment.

The following room dealt with “Perspective.” Petrus Christus’s Virgin and Child with Saints Jerome and Francis (Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum) and Bouts’s Coronation of the Virgin (Vienna, Akademie der bildenden Künste) were shown to suggest they were the first painters in the Low Countries to consistently apply linear perspective. Several classic video games, such as Doom and Quake, were included in a video that discussed the illusion of three-dimensionality today.

The “Banality” section asserted that Bouts included seemingly redundant figures and objects in his paintings to give them a more “realistic” character. The figures in Christ in the House of Simon the Pharisee (Berlin, Gemäldegalerie) are astonishing, but the most impressive loan was without a doubt the spectacular Triptych of the Descent from the Cross (Granada, Capilla Real). After more than 500 years (!), Bouts’s most monumental work returned for the first time to the city where it was created. Its quality is undeniable, but the triptych is in desperate need of a thorough conservation treatment, which will take place at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) in Brussels in the years following the exhibition. It should be noted that these works were confronted with a video from Pier Paolo Pasolini’s black-and-white film Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (“The Gospel according to Matthew”). The director employed amateurs and locals as actors in order to get closer to the essence of the Gospel, and the film’s juxtaposition with Bouts’s painted scenes from Golgotha worked well on an atmospheric level.

Bouts’s most famous work, the Triptych of the Holy Sacrament (Leuven, Saint Peter’s Church) with the Last Supper at its center, was presented in the “Finale.” This documented work was commissioned by the Leuven Brotherhood of the Holy Sacrament for their chapel in Saint Peter’s Church where it is still preserved today, but what a joy it was to see it up close and well-lit in the exhibition. Despite the specific instructions imposed on the artist in the contract and after four years of work, Bouts delivered a masterpiece. Indeed, it contains all the elements explored in the exhibition and it is a monument of the Northern Renaissance.

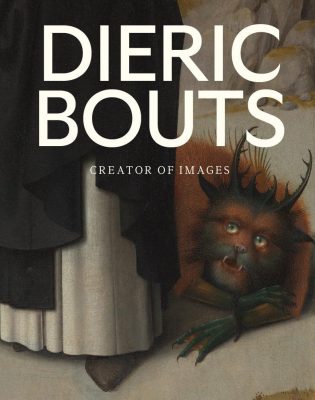

The bold approach of the exhibition’s organizers and the impressive international loans are praiseworthy. This resulted, however, in very hybrid presentations with skewed comparisons that might have been entertaining for a wider audience, but made specialists scratch their heads. The quality of the major works is undeniable and made the exhibition worth the trip, but different curatorial choices could have contributed to a better understanding and appreciation of Bouts’s oeuvre. Those who missed out on this exhibition can still get a rare second chance to see some of the works it featured in Atelier Bouts at M Leuven (February 16 – April 28, 2024). This smaller display of six key works, including paintings from Leuven and Granada, explores the artist’s production through technical examination and restoration of his works. Such approaches doubtless would have contributed more to Dieric Bouts: Creator of Images.

The nicely produced and elaborately illustrated catalogue does not follow closely the organization of the exhibition. Instead, the book is divided into three sections, with essays and shorter texts by a dozen authors with different backgrounds. “Bouts and the Fifteenth Century” deals with such topics as the university of Leuven, the library of Park Abbey, and the artistic milieu of Bouts. “Bouts as a Creator of Images” focuses on the devotional paintings, connections with Italy, perspective, and landscapes. A final section contains contributions with a transhistorical approach. Dispersed throughout the book are eleven catalogue entries focusing on individual works. Remarkably, some of these focus on paintings that were not included in the show: Ecce Agnus Dei (Munich, Alte Pinakothek), Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi (“Pearl of Brabant”) (Munich, Alte Pinakothek), and Diptych with the Justice of Emperor Otto III (Brussels, Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium). A list of all the loans is included at the end. This book does not aspire to replace the catalogue of the 1998 exhibition Dirk Bouts: A Flemish Primitive in Leuven or the 2005 catalogue raisonné by Catheline Périer-D’Ieteren, but it does provide fresh insights about the master nonetheless.

Jeroen Luyckx

KU Leuven