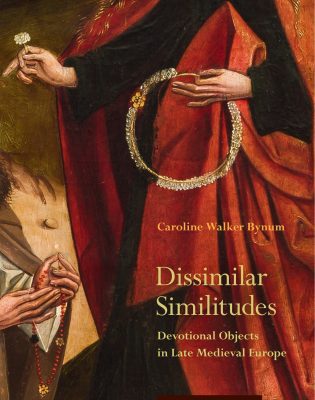

In her latest book, Dissimilar Similitudes: Devotional Objects in Late Medieval Europe, Caroline Walker Bynum delves even deeper into the material world of the devotional object during the long Middle Ages. The author’s unmistakable erudition in material culture has provided her with a rich corpus of objects from which to draw. In this volume of collected essays, she starts with notable phenomena such as the Christ cradles from the beguinages of the Low Countries, discussed in Chapter 1, and the crowns placed on Virgin Mary statues in the German convent of Wienhausen, the subjects of Chapter 2. It is well known that “a plethora of things” in the late Middle Ages both embodied the exuberance of spirituality and fueled the growing suspicion among those intellectuals who recognized evil in the unbridled “celebration of the thing.” Dissimilar Similitudes, however, aspires to being more than a historical discourse on the anchoring of objects in their spiritual Sitz im Leben. Walker Bynum writes: “I emphasize the way in which each object itself not only stresses its tactility (its thingness, so to speak) but also, in doing so, gives contradictory visual signals simultaneously” (p. 51). The beguinage bed, for example, is multi-semantic and multi-functional; it signifies both a motif and a sanctuary. The bed has a tangible purpose in the liturgy and a personal role in the spiritual desires of the nun. Such ambivalence is also inherent in the Marian crowns: “The object itself tells us that it is full and empty, glorious yet lacking, achieved yet waiting” (p. 51).

The devotional object is “something” and at the same time “nothing;” it escapes us in an in-between space that is difficult to define. Therefore, the objects that Walker Bynum highlights in her book hover on the boundary between earthly and heavenly life. Moreover, the momentary and the timeless seem to implode as soon as the object’s materiality enters liturgical space. The object dwells in the rarefied space of the “not yet, not here” (p. 53). However, it is exactly there, in the interspace of prayer, of ritual, of trance, where it finds its multiple meanings.

The essays in Dissimilar Similitudes – referring to the unstoppable tension between likeness and unlikeness – also pursue a hermeneutical ambition. Walker Bynum describes the dynamic capacity of religious objects for displacement across time and space. In doing so, the author ensures that her collection of essays will be of transcultural relevance for today’s scholars.

In Chapter 3, “The Sacrality of Things,” and in Chapter 4, “The Presence of the Object,” Walker Bynum elaborates on what she calls the contradictory visual signals of things. From the writings of the fifteenth-century theologian Johannes Bremer, in which the Franciscan discusses a hierarchy of the sacred value of the image, it becomes clear that resemblance plays no role in this value. What plays a role is “presence.” The presence of the sacred prevails in different types of objects: sometimes even in two-dimensional images of which a living entity was believed, in relics of course, but above all in the Eucharist. The Eucharist is fascinating in this context, because it lacks any similitude in its “presence.” Yet the host, this aniconic object, constitutes the purest, most holy presence of Christ. It is here that Walker Bynum calls for an exploration of non-figurative sacred presence in a transcultural perspective, in conjunction with anthropologists, ethnologists, historians of religion, etc.

“The Presence of Objects,” as Chapter 4 is titled, can be both overwhelming and intimidating. Objects can be used negatively and strategically. Antisemitic historical narratives of late medieval devotional objects, such as bleeding hosts, used as attacks on Jewish communities, are well known and well documented. Walker Bynum, however, wants to understand the contemporary relationship – that of tourists, visitors, of you and me – to this material heritage. She studied visitor and museum guides to wafer blasphemies, which refer to items such as the table in Sternberg’s baptistery on which Jews were alleged to have tortured consecrated hosts until they bled in 1492. Whereas in the previous chapter Walker Bynum called for a dismantling of the Eurocentric gaze, here she asks for a debate with local residents, tourists, curators, pastors, scholars, and Holocaust survivors about sensitive material remnants and memorials from the Middle Ages. “Those involved must recognize that neither erasure nor contextualization will remove the infamy of such things from memory. Thus, it is hard for me as a historian not to feel that it is best for us to encounter the objects themselves” (p. 181).

Chapter 5, “Avoiding the Tyranny of Morphology,” returns to the axiom of upgraded Christian sacred presence in the dissimilatory object. Here the Eucharist remains the challenge for undertaking comparative research with Hindu culture. Walker Bynum, however, denounces those conventional intercultural comparisons between morphological “look-alikes.” She claims a comparative interreligious enquiry that scrapes the resemblance (“appearance”) to the deeper core, which she has previously called the locus in the materiality of the object. Walker Bynum is now spot-on both at the level of the ambivalently “similar” object (the relic, the Eucharist) and of comparative intercultural hermeneutics. After all, it is not morphology that discharges intercultural meanings, but rather the meaning within the matter, regardless of their outward characteristics. She writes: “Metaphor, or what one of the greatest of Christian theologians [Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite] called ‘dissimilar similitudes,’ is thus the best image I can find for true comparison” (p. 220). The moment of this methodological discharge flows seamlessly into the sixth and final chapter: in my opinion, the mise-en-abîme of the volume.

Chapter 6, “Footprints: The Xenophilia of a Medievalist,” forms the keystone that locks the six essays together. The footprints of Christ and of Buddha, both the last traces of the sacred body and the eternal memories of a bygone materiality, articulate object and place, iconic and aniconic, absence and presence. Or, as Georges Didi-Huberman (whose related essays on dissemblance and resemblance are, as far as I could ascertain, absent) writes: “Dans tous les cas, l’empreinte fait de l’absence quelque chose comme une puissance de forme” (La ressemblance par contact, 2008, p. 55). The footprint dwells pars pro toto and uncompromisingly in the in-between space. It dissolves the global differences and particularities across cultures. That is why Walker Bynum calls the footprint an image of the love for the other, the Other, and thus for the xenophilia that the medievalist must display at all times: “Hence the medieval footprint in its many guises and permutations can perhaps serve as a metaphor for what scholars pursue – with phobia as well as philia. The other we seek to know, whether text or object, is paradoxical – on the one hand, a conjuring up of an absent something that has left only a trace, yet on the other hand, a thing powerful in and of itself” (p. 258).

“The widening gap between imprint and the disappearance of Christ” (p. 247), as well as the “void of the almost” between the hands of the Noli me tangere, is the mysterious Zwischenraum, the breach in time, the mandorla even, in which this book took form. Thus, it is hard for me not to sense that Caroline Walker Bynum presents her legacy in Dissimilar Similitudes, in which the longing, the healing and the many sighs for the future of our disciplines in the humanities and the social sciences constitute authentic and exemplary emotions.

Barbara Baert

KU Leuven