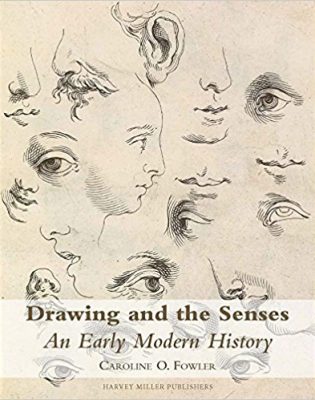

Caroline O. Fowler’s thoughtful study of early modern printed drawing books through the lens of the senses is a compelling contribution to the study of drawing both north and south of the Alps. The book provides a much-needed theoretical grounding for didactic drawing manuals based on contemporary literature on the arts, the senses, and the passions. The genre of printed drawing book as explored here consists almost entirely of printed images, without explanatory text, of fragmentary examples of facial features, body parts, and partial or full figures.

Scholars have considered printed drawing books via national schools (Bolten 1985, Dickel 1987, Greist 2011), as evidence for a shift towards disegno in Venice (Rosand, 1970), and in a small number of articles exploring specific titles and their genesis. This study finds novelty in its engagement with early modern philosophy and religious theory as a framework for understanding the structure and function of the fragmentary drawing example. Fowler’s interest in the genre of printed didactic manuals was born from her doctoral research on the drawing book of Abraham Bloemaert, Artis Apellae liber (1651-56). By using Bloemaert’s work to explore the nature of artistic training, Fowler is able to make a rich and nuanced discussion of a work that in many ways appears derivative of earlier Italian examples.

Fowler begins with a review of previous literature on the printed drawing book and its supposed origin in well-known treatises on disegno, such as those by Leon Battista Alberti, Alessandro Allori, and Francisco de Hollanda. She identifies the main unanswered questions about the works, including intended audience and lack of text. This introduction to the genre allows her to focus, in three extensive chapters, on what she convincingly argues are ideas crucial to the understanding of the method wherein drawing is taught via fragmentary compositions of the sensory organs of the human body.

The first chapter delves into Euclidean ideas about the point and the line as interpreted in Albrecht Dürer’s famous drawing manuals. Fowler argues that the point and the line are the way for the artist to move from “the sensory and temporal to the invisible and eternal”(63). That the artist must move beyond life studies to create from internal knowledge is discussed in art theory from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, most famously by Lomazzo. Dürer’s interest in the point and the line and other geometric examples did not have a long life in drawing manuals. The method that came to take over drawing education was Aristotelian and based in the senses, foremost in the eye (69).

In Chapter 2, Fowler argues that the focus in printed drawing lessons on sensory organs parallels literature on artistic theory, claiming that true understanding arrives in the mind through the senses. She connects practice and theory to argue that a focus on the sensory organs was not simply a practical way of teaching amateurs (and one that reflected professional training), but that it also had a theoretical function (76). Drawing from a range of theoretical writing, from Aristotle to Armenini and Lomazzo, Fowler explores how knowledge is imprinted on the soul and in the memory; she draws connections between early modern concepts of printed words and images and the creation of knowledge. In Fowler’s argument, the artist’s brain is a tabula rasa that must be filled with and imprinted upon by whatever s/he gathers from the senses in order to be creative. One of Fowler’s most compelling observations is the connection between Zuccaro’s theoretical treatise, L’idea de pittori, scultori ed architetti (1607), and the birth of the printed drawing book. Her discussion could benefit from engagement with Giuseppe Maria Mitelli’s Esemplari per disegnare di rame no. 12 (c. 1699), where the first five plates are organized around the senses with eyes on a plate for sight and ears on a plate for hearing, etc.

The final chapter discusses the drawing books of Rubens and Bloemaert. Discussion navigates between extensive treatments of a number of big ideas, including the goal of the artist (to move the viewer), caritas and the movement of the soul, and the depictions of the passions in art. This last point is explored in depth through the example of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper and the artist’s ability to turn specific, observed examples into general cases. Fowler makes the argument that “the crux of historia and its potential to move viewers depended upon the examination of the inward and outward turns of the soul and its realization in outer expression (149).” Following this, she argues that examples in drawing books served to train the user in how to make visible the internal qualities of mankind. The main argument comes together here: in learning to draw specific examples, the artist (amateur or professional) becomes capable of eventually creating the universal.

Fowler’s Epilogue explores Giovanni Morelli’s system of attribution through fragments such as hands or ears as a progression of sorts from the fragmentary drawing lesson. The chapter is suggestive, if not always convincing; her proposal that the same amateurs who collected drawing books (whether or not they actually used them to learn drawing) also used those books to learn connoisseurship finds little support in the evidence (153-154).

In sum, Fowler’s book is thoroughly researched, thoughtfully argued, and beautifully illustrated. There are a few minor editorial oversights, but these do not interfere with the author’s argument or the overall effect of the book. The author has added great theoretical depth to debates about this interesting corpus of artistic material. In so doing, she opens up new ways of thinking about the fragmentary drawing example as more than a practical approach to drawing instruction. The study will serve as a basis for further research into the theoretical parameters of drawing instruction and its aims in the early modern era.

Alexa Greist

Art Gallery of Ontario