This excellent catalogue was designed to accompany the exhibition of 67 of 134 Dutch drawings donated recently by Leena and Sheldon Peck to the Ackland Art Museum at UNC Chapel Hill. The book represents one of the donors’ chief goals in making the gift: to anchor the collection among its peers worldwide as an important source for the study of Dutch art of the seventeenth century. In this task it succeeds admirably. Robert Fucci’s catalogue entries are exemplary in their methodology, both illuminating the history and essential qualities of the drawings and delving deeply into broader issues, mostly iconographic, that inform the objects. In sum, the volume under review puts the Ackland on the map for scholars of Dutch drawing and will prove to be the bedrock for all future research on this material.

The remainder of this review addresses individual drawings about which I have views that either diverge from or expand upon those of the author, some having to do with interpretation and others with style and attribution. The first piece under consideration, Andries Both’s remarkable Crowd Outside an Inn with an Art Seller (cat. 14), contains many puzzling iconographic features, some of which defy easy explanation. To my mind, however, there is no question that the crowd of figures, villagers who seem engrossed in their own everyday concerns, remain essentially oblivious to the so-called art seller. The rather flashy brushwork in sepia that defines an upper canopy of an awning and perhaps vegetation mutes the rather anomalous presence of that figure, who may or may not have been part of the original conception. Whether the scene’s protagonist is really an auctioneer is also open to question. He may just as well be a quack peddling his wares – in other words a charlatan.

Rembrandt’s Seated Man Warming His Hands by a Fire (cat. 38) also poses a curious interpretive puzzle. I would like to posit that the elderly figure represented here originally sat in the center of a room, and that the artist later transformed the setting to place him before the open fire. This would explain the rather summary indication of the open hearth, the fire and the fireplace surround sketched at the right, not to mention the heavily reworked positioning of the man’s hands. That this aged man is lost in thought is, to my mind, beyond dispute. In this state it is almost inconceivable that the figure would actively gesture with his hands, as shown here. The change in context that I am proposing supplies a rationale for Rembrandt’s decision to modify the hands, giving them a suitably active role. It also would explain why the man’s left foot, closest to the fire, lies in deep shadow, instead of being strongly illuminated as might be expected. An early copy of the drawing illustrated by Fucci (fig. 38.1) helps to clarify the situation in that its maker failed to understand the visual consequences of Rembrandt’s transformation.

A Courtyard in Italy (cat. 26), one of Thomas Wyck’s most distinguished drawings, fortunately poses no interpretive enigma. Here the modulation from intense light to areas of mid to deep shadow is superbly calibrated. Wyck realized the myriad gradations through his understanding of the relationship between hue and value. For me hue is gauged by the degree of modulated grayness indicative of the relative presence or absence of direct light. By contrast value measures the degree of clarity of detail whether in light or in shadow. In all instances detail is represented with remarkable clarity throughout which is a brilliant measure of the limpid quality of Mediterranean light in contrast to the far more atmospheric light of northern Europe.

A second drawing given to Thomas Wyck in the catalogue, Interior with Bed (cat. 49), is so utterly different in character from A Courtyard in Italy that I cannot believe that it could be by the same hand. All details are summarily characterized without the subtle gradation of shadow so evident in A Courtyard in Italy and all details are delineated in a formulaic, heavy-handed manner characteristic of a rank amateur. I would have great difficulty knowing how to catalogue Interior with Bed other than as “Anonymous, Dutch School (?),” or feel comfortable proposing a date for this sheet.

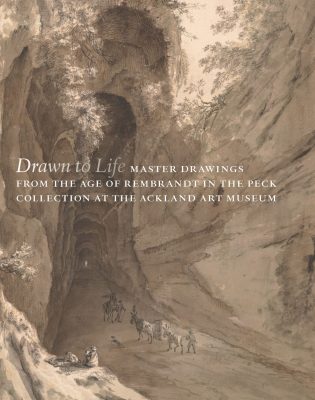

The collection contains two other landscapes that are extraordinary examples of Dutch artists intoxicated by the dazzling effects of sunlight. The first, The “Grotto of Virgil” at Posillipo near Naples (cat. 55) by Willem Schellincks, forms an interesting counterpart to Wyck’s Courtyard in Italy. My observations concerning Wyck’s modulation of light and shadow, so rich in hue but so transparent in value apply equally in this dramatic work by Schellincks. The sheer scintillating effects of light and the remarkable depths of shadow defining this deep cleft in the bedrock support Fucci’s belief that this drawing is the magnificent result of this artist’s direct observation. No less striking is Joris van der Haagen’s View in the Hague Woods (cat. 33). Despite its highly finished state, this study demonstrates Van der Haagen’s sheer delight in recording strong sunlight playing across the deciduous trees and the shrubbery defining the verge shimmering in the sparkling light. The backdrop of transparent floating clouds only enhances the power of direct sunlight playing across the vegetation. This study embodies the sheer joy of penetrating observation translated into compelling visual realization.

Knoll above a Pond (cat. 34), which Fucci tentatively attributes to Herman Naiwincx, is one of the most distinguished landscape drawings in the Peck Collection This drawing is in all aspects the epitome of refinement. Its atmosphere is palpable yet delicate, the contrast between light and shadow perfectly nuanced, and like Wyck in his Courtyard in Italy the treatment of value in no way obliterates even the most minute detail. The entire subject is energized by the idiosyncratic definition of space with rooftops perched at the upper right in contrast to a church spire glimpsed in the left far distance. Could this possibly represent the height of the coastal dunes facing the North Sea or conversely the sloping land leading up to the Hooge Veluwe north of Arnhem Although we may never know, I think that the still unidentified artist who created this masterpiece belongs somewhere in the orbit of Jacob van Ruisdael, Adriaen van de Velde, or Jan Wijnants. If indeed by Naiwincx, this drawing would warrant a radical reassessment of his significance, distinguishing him as a major landscape draftsman of the Dutch school.

From an intellectual perspective this catalogue is a monumental achievement. It is also a splendidly designed book, beautifully illustrated and enriched with a sprinkling of enticing details that underscore so many of the salient characteristics of Dutch draftsmanship. For those who have experienced these drawings at first hand the catalogue will serve as an enduring reminder of a delightful encounter, and for others provide a stimulating invitation to see the originals.

George S. Keyes

Waldoboro, Maine