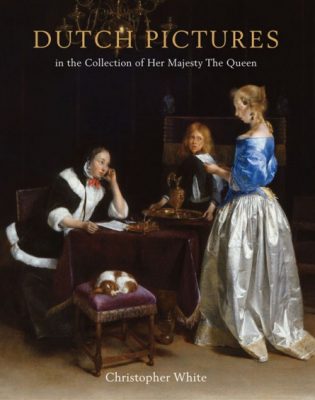

This past spring (2016), there was much activity surrounding the Dutch pictures belonging to the British Royal Family who hold one of the largest and most significant private art collections in the world. In early March a stunning exhibition of Dutch genre paintings from that collection opened at The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, in Edinburgh, Scotland (see the review in HNA Review of Books, November 2016). And several weeks later, in April, there finally appeared Sir Christopher White’s long-anticipated revised edition of the catalogue of Dutch paintings (sixteenth to eighteenth century) belonging to Her Majesty the Queen. This splendid new edition, marked by production values of uncompromisingly high quality, provides welcome and much-needed changes to the venerable edition that was published in 1982 by Cambridge University Press.

What is most immediately striking about the new catalogue, beyond its sheer physical size that is, is the replacement of all of the black-and-white illustrations from 1982 with ones in color. Moreover, important condition and technical notes have been added to each catalogue entry, ably supplied by Rosanna de Sancha of the Paintings Conservation Studio at The Royal Collection, Windsor. White himself has taken into greater account the opinions of early nineteenth-century connoisseurs, which inform the entries on many of the paintings, especially those whose provenance can be linked to the Prince Regent’s (the future George IV’s) sizeable and important collection from the now-demolished royal residence, Carlton House. And, in addition to including several pictures omitted from the first edition, White has also reviewed each entry from the prior catalogue in terms of attribution. This induced him to reclassify a number of paintings, most extensively those associated with Rembrandt and his school. Although the cataloguing numbers from the first edition have been retained, in this new one “in cases where works have been reattributed, entries maintain a placeholder in their original position, but full entry and image have been moved so that they appear under the correct artist and as a result are in non-chronological order (p. xiii).”

The book opens with a lengthy survey of the collecting activities of British Royals from the days of Elizabeth I to the present Queen. In effect, it duplicates the essay that White penned for the first edition, only with some minor editorial changes, the addition of illustrations (all in color), and bibliographical updates. This essay is essential reading for anyone interested in the vagaries and vicissitudes of royal collecting through the centuries, affected as it was by the whims and tastes of the collectors, (Charles I and George IV most prominent among them), by ever-changing aesthetic ideals and evolving market conditions, and the political and economic repercussions of such cataclysmic events as the English Civil War and the French Revolution. Particularly noteworthy are White’s discussions of Gerrit van Honthorst’s sojourn in England in 1628 and his continued work for the Crown and extended court in the ensuing years, the sale of paintings from Consul Joseph Smith’s collection in Venice to George III in 1762, and the pièce de résistance, the author’s thorough examination of the formation, development, and display of George IV’s aforementioned collection, many of whose Dutch paintings remain part of the Royal Collection today. There follows the comprehensive catalogue, presented in a much more impressive manner than its counterpart of 1982, as outlined above.

If this reviewer has one quibble with Dutch Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen it is the extent to which the bibliographies in both the introductory essay and the catalogue entries themselves have been updated. White claims to have “attempted to bring the extensive bibliography and exhibition history up to date (p. ix),” but I did not find strong evidence of this. To be fair, given the veritable mountain of publications on Dutch art that have appeared since 1982, it would be unreasonable to expect any scholar to be au courant with virtually every new contribution to the field. Nevertheless, there are some surprising omissions here, which occasionally impact White’s discussion. To cite just a few examples, Constantijn Huygens’s views on Rembrandt and Lievens (p. 22), have been investigated by many scholars besides Seymour Slive, whose Rembrandt and His Critics of 1953 provides the sole citation in the accompanying footnote. What would have been particularly useful in this context is Inge Broekman’s short but very illuminating book of 2005 that addressed the role of painting in Huygens’s life and career. Similarly, White’s otherwise valuable assessment of the Van de Veldes’ English period (pp. 28-31) would have been strengthened if he had been familiar with Remmelt Daalder’s recently published dissertation of 2013 –recently published as a book–on this talented father-and-son team, because it corrects to some of the material set forth in Michael S. Robinson’s earlier studies of these artists. Lastly, I was astonished to find my doctoral dissertation of 1987 cited in connection with Gerrit Dou’s Maidservant Scouring a Brass Pan at a Window (p. 139) and not my related book, Paragons of Virtue; Women and Domesticity in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art, published in 1993.

In the end, my minor disappointments with the bibliography are not meant to detract from White’s achievement. The revised edition of Dutch Pictures in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen is a welcome addition to the field, which, like its predecessor of 1982, will serve as the authoritative source concerning Dutch paintings in this distinguished collection for decades to come.

Wayne Franits

Syracuse University