German printmakers of the early sixteenth century were the first to experiment with color printing, using multiple woodblocks for each tone to create composite images, often called “chiaroscuro prints.” While this phenomenon has been studied in surveys of German printmaking, such as Giulia Bartrum’s German Renaissance Prints 1490-1550 (1995) or David Landau and Peter Parshall’s The Renaissance Print, 1470-1550 (1994), no one has examined this phenomenon exclusively or as closely as Elizabeth Savage, Senior Lecturer in Book History and Communications, School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Using the matchless collection of the British Museum, Savage focuses on printmaking technique more than on individual artists or regions, though she does devote separate chapters to major developments before the Reformation in both Augsburg (Hans Burgkmair and Hans Weiditz; Chapter Three) and Strasbourg (Hans Baldung and Hans Wechtlin, as well as printer Johann Schott; Chapter Four). Chapter Five discusses pre-Reformation devotional images (including Schäuffelein and Altdorfer, nos. 40, 47), and Chapter Six focuses on the remainder of the century (e.g. Holbein title pages, nos. 54-55; copies after the Beham brothers, nos. 51-52, 61). Chapter Seven features ornament prints, architectural views, and decorations for home walls, whose fragility has left very few examples. Along with important later contributors, such as Tobias Stimmer (no. 69) and Wendel Dietterlin (jigsaw etching no. 73), Chapter Eight also includes copies after Italian engravings and multicolor graphics and images on book title pages.

One major contribution of her study is to foreground the prequel to the more familiar story (Chapter Two) of the rival color woodcuts during the first decade of the 1500s by Lucas Cranach in Wittenberg (nos.11, 14-16) and Hans Burgkmair in Augsburg (nos. 12-13). In doing so, she underscores the major technical contributions already in the 1470s by the book publisher Erhard Ratdolt (first in Venice and then in his native Augsburg after 1486), especially in an astronomical book of 1482 (cf. no. 8). But some color letterpress book texts were already added in the wake of Gutenberg. Burgkmair apprenticed with Ratdolt in Augsburg in the 1490s and produced a number of colored illustrations in Ratdolt’s Augsburg prayerbooks (no. 10).

Altogether, Savage’s study spans 150 years, ending around 1600, thus encompassing later developments than most surveys, focusing chiefly on innovation, usually address, including the addition of a color tone block, around and after 1600, to a print from the previous century, often by Dürer or Beham (Chapter Eight; also discussed by Walter Strauss, Chiaroscuro, 1973). In the process, she also considers the varied audiences for these prints: farmers, who utilized almanacs and calendars; devout Christians with their devotional images; and aristocratic patrons of such works, including the Holy Roman Emperors Maximilian I and Charles V, whose prints could include gold accents.

Most works under discussion are single-sheet works, but rubricated book texts also formed early foundations for later color printmaking. Of course, long before the printing press, already by ca. 1300, color-block printing by stamping was employed for such late medieval media as wallpaper (not included) and textiles. Numerous fifteenth-century woodcut prints (of the few that survive) were hand-colored or stenciled (Chapter One; no. 6). Others, in tandem with similar “chiaroscuro drawings,” were printed on toned paper. White-line woodcuts (no. 5), most often associated with Swiss artist Urs Graf (ca. 1485-1529), use bright lines from the paper against a black inked surface, in an inversion of the normal black lines on white paper.

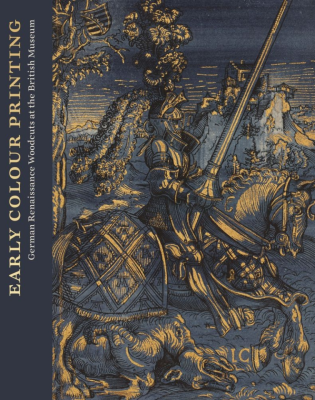

While Savage’s book is both comprehensive and scholarly, its clear prose also speaks to a general public, and includes her initial careful definitions of the components of her analysis, especially prints, artist-designers, and cutters (Formschneider). One bonus of this book is the full-page illustration of prints under discussion, placed at the appropriate point in the text. Savage also distinguishes between prints that add color to black/white outlines and prints that only cohere as a whole when all the blocks are printed together (a major contribution in Italy after 1516 by Ugo da Carpi, who got a privilege in Venice for this technique, which he claimed as his own invention).

In short, her book is rigorous yet accessible, focused on objects but with a sense of the overall contexts and developments. And its range of objects and images goes well beyond the usual focus, including this review, on better-known names especially from the crucial first decades. This study readily serves as both a reference work and a survey introduction for German colored woodcut prints of the long sixteenth century. For the next great moment in color printing at the end of the sixteenth century, however, one must turn to Hendrick Goltzius, consulting Nancy Bialler, Chiaroscuro Woodcuts: Hendrick Goltzius (1558-1617) and his Time (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 1992).

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania