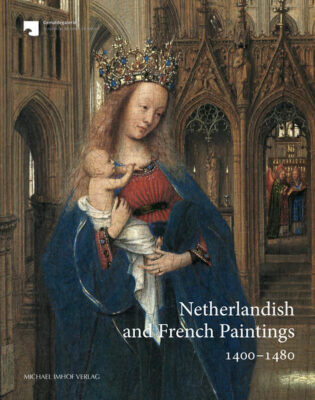

This handsome collection catalogue provides in-depth studies of the paintings in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, by artists who were active before ca. 1475-80 in the Burgundian Netherlands and France. Its fifty-two entries combine a wealth of new technical information with the art historical judgment and accumulated experience of the Berlin curators, led by Stephan Kemperdick. The paintings catalogued are among the most important surviving works from a period of transformation in the ambition of painters. The work of leading artists of this time – Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Jean Fouquet, Dieric Bouts, Hugo van der Goes, and Hans Memling – is so well represented in Berlin in no small part because the Gemäldegalerie was formed by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century scholar-curators who also shaped the field of study of early Netherlandish paintings – among them Gustav Waagen, Hugo von Tschudi, and Max J. Friedländer.

The catalogue intersperses Netherlandish and French paintings in chronological, rather than alphabetical order by artist. Works attributed to a single artist, workshop products, and copies are likewise arranged chronologically within a group so that the book constitutes a form of narrative of the period. With the exception of Jean Fouquet’s great diptych panel, Etienne Chevalier and Saint Stephen, for the treasurer of Charles VII of France (no. 36), the pictures classified as French were made by artists of Netherlandish origin or working in territories then held by the dukes of Burgundy from the French crown.

Katrin Dyballa and Stephan Kemperdick edited and oversaw the project, writing almost all the entries. Kemperdick undertook those for Van Eyck and his workshop (apart from the Holy Face of Christ after Van Eyck [no. 13], contributed by Christine Seidel), as well as those for Petrus Christus, Jean Fouquet, Simon Marmion, and Hugo van der Goes (with the exception of Erik Eising’s entry for the tüchlein of Mourners from a Descent from the Cross [no. 45]). Dyballa’s contribution includes the important group of paintings from around 1400 (other than Seidel’s entry on the Coronation of the Virgin roundel [no. 3]), what is here called Group Master of Flémalle and Jacques Daret, and the extraordinary group of works by Van der Weyden and his followers. Bouts and Memling also fall to her portion, as does Albert van Ouwater.

Substantial technical notes begin every entry and are each signed by the conservator who undertook the examination. These contributors are Sandra Stelzig, Beatrix Graf, Maria Zielke, Babette Hartwieg, Maria Reimelt, and Anja Wolf, with Hartwieg in a coordinating role as head of conservation. Their texts discuss each painting’s support, including information about the frame and the panel construction (with dendrochronology often supplying key data for approximate dating), the ground, underdrawing, paint and gold application, and conservation history. When the author of the technical note also restored the object, this section illuminates the artist’s working process especially well, notably in Graf’s discussion of Van der Weyden’s Miraflores and Saint John Altarpieces and Van der Goes’s Monforte Altarpiece (nos. 26, 29, and 44 respectively). The discussion in the body of the entries written by the curators takes this technical information into account, outlines provenance and iconography, lists copies and closely associated works, and gives particular consideration to attribution and date and to the reconstruction of dismembered ensembles.

Technical notes and entry texts are richly illustrated, mostly in color, making a sumptuous book. Illustrations of the backs of panels, x-radiographs, and infrared reflectograms, including many close-ups for better legibility, together with details in normal light, overlays, reconstructions, and comparative works contribute immeasurably to the reader’s understanding of the issues raised by each object. The number of illustrations (an average of eight to twelve per entry and twenty-three each for the Monforte and Middelburg altarpieces) undoubtedly also imposed some limits on text length. In their Preface, Dyballa and Kemperdick note that, to save space, sections on the history of research on each object were omitted, as were short biographies of each artist. The history of research is still succinctly laid out in the sections on attribution and date, supplemented by lists of short references in each entry. Biographical information is less consistently provided, apart from the artists’ life and death dates included in the table of contents. In view of the uncertainties, not to say controversies, that still surround the relationships between painters and the formation of careers in this period, more biographical detail integrated into the entries would have helped the reader.

The publication of a parallel English translation makes the catalogue more accessible, and this review is based on the English edition. However, the challenges of translating such a complex, multi-author book need to be mentioned. Three translators and a copy editor accomplished this task (see the Foreword by Dagmar Hischfelder, director of the Gemäldegalerie). The specialized language of the technical notes posed particular challenges, and a cognate English word was sometimes chosen over an idiomatic one: poliment (Poliment) instead of bole as the preparation for gold leaf in the earliest paintings; quicksilver (Quecksilber) for the element mercury in a pigment; pencil (a sixteenth-century tool), as the translation of Stift in more than one instance, when stylus or another more general word for a tool to achieve a dry line was meant (pp. 186, 494). There are also translation problems in the curatorial sections. Thus, the discussion of the attribution of the Virgin and Child with Butterflies (no. 4) begins: “Von Beginn an wurde die Entstehung der Berliner Madonna im höfischen Kontext verortet – sei es als ein Werk der Brüder Limburg, sei es als eines von Maelwael bzw. aus dessen Umkreis. Sie alle waren am burgundischen Hof in Dijon für Philipp den Kühnen tätig, die Limburg-Brüder von 1409 bis zu ihrem Tod in 1416 zudem nachweislich auch für den Herzog Jean de Berry in Bourges” (p. 48), but the translation as: “From the outset, though, the Berlin Madonna originated in a courtly context – be it a work of the Limbourg brothers, or by Johan Maelwael or his circle. All were active at the Burgundian court in Dijon for Philip the Bold (1342-1404), the Limbourgs from 1409 until their death in 1416, and also demonstrably for Jean de Berry in Bourges” (p. 47), adds an extra clause and misplaces the Limbourg brothers’ patronage. The reader would do well to consult the original German text when puzzled.

By its nature, a collection catalogue is concisely argued around the issues presented by individual paintings. At its best, as here, it is an authoritative record, uncovering and sharing information most readily available to the conservators and curators who work directly with the objects, while providing larger insights and hypotheses that stimulate new thinking about single objects or object types. Much new physical information is presented in this catalogue. For example, the Eyckian Crucifixion (no. 5) was painted on a fine linen canvas, not transferred from panel to canvas as previously thought, and hence it joins the Virgin and Child with Butterflies (no. 4) as an early use of “oil-based paint” (p. 54) on a fabric support. Infrared reflectography of Van der Goes’s tüchlein of Mourners from a Descent from the Cross (no. 45) revealed the presence of a grid, presumably an aid for transferring the design (p. 494, fig. 45.4); its counterpart of the Deposition now belonging to the Phoebus Foundation has a similar grid. The Italian provenance of this and many other surviving tüchleins suggests that they were aimed at an Italian market. Eising notes in his entry that this half-length diptych composition must also have remained available in Flanders since Memling made use of it. One wonders, in view of the presence of the grid, if a transfer process was used to make multiple versions of this moving devotional subject.

In the entry for the Miraflores Altarpiece (no. 24), a key documented work by Van der Weyden given to the charterhouse of Miraflores by John II of Castile in 1445, Katrina Dyballa is inevitably building on the earlier work of Rainald Grosshans and Stephan Kemperdick. Nonetheless, she provides new insights into the triptych’s framing and use by tracking descriptions of it in the 1840s when in the collection of William II of the Netherlands and on its acquisition in Berlin in 1850, in part through unpublished correspondence in the Zentralarchiv of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. She quotes a letter of November 26, 1850, from Sulpiz Boisserée to museum director Ignaz von Olfers, attesting to the elderly collector’s enthusiasm for the original frame, then still surviving, and for the way the frame design was continued in the painted architecture of the panels (pp. 274, 281, n. 73). It is clear from these sources that the two wings were meant to close, one over the other, to cover the equal-sized central panel, making the triptych readily moveable. Whether it actually saw use as a portable altarpiece before its donation to the charterhouse remains in question, as she notes. Discussion of the structure and function of Berlin’s remarkable group of altarpieces is particularly stimulating, and extends to fruitful speculation on lost elements. Thus, Kemperdick suggests, based on a re-reading of early descriptions of the Saint-Bertin Altarpiece (no. 37), that its lost central shrine of precious metals and gems was not made in the current style of separate statuettes under arcades, but featured figures emerging in relief from a gilded ground in emulation of the richness of Carolingian goldsmithwork and in celebration of the abbey’s distinguished history and Guillaume Fillastre’s sophisticated patronage.

Prominent among the many entries that raise broad issues is Kemperdick’s discussion of the Van Eyck painting now titled Portrait of a Man with a Red Chaperon (so-called Giovanni Arnolfini) (no. 7). The identification of the sitter in this portrait employing Van Eyck’s usual format is dependent on that of the man with the same features who is the subject of the utterly exceptional double portrait of 1434 in the National Gallery, London. Consequently, Kemperdick’s entry is a concise and thoughtful re-examination of the London painting too. He questions whether any association with a member of the Lucchese merchant family of Arnolfini can be derived from the descriptions of the London double portrait in the 1516 and 1523/24 inventories of the collection of Margaret of Austria (first suggested by Crowe and Cavalcaselle in 1857). He notes the oblique manner in which the man in the London double portrait is named in Margaret’s inventories – as “qu’on apelle Hernoul le Sin…” in 1516 and in the second Mechelen inventory, “nomme le personnaige Arnoult Fin”.[1] As Kemperdick points out, the lists of paintings in the inventories usually give the name of a portrait subject (or, it might be added, describe the dress and accessories if no name is given). Hence, the phrase “called Arnoult Fin” suggests a nickname such as Arnoult the Shrewd or indeed an element of fantasy superimposed on the portrait. Here he cites Marco Paoli’s argument that the name Arnoult was a nickname for a cuckold,[2] making a possible link to the cynical Ovidian verses first recorded in 1599 as being on the now long-vanished frame of the picture. Kemperdick flirts with the possibility that both panels might depict Van Eyck himself, but he admits (p. 77) that we can know little with any certainly about the identity of the subject common to both portraits. This second statement seems true enough, and it was indeed already evident following Lorne Campbell’s meticulous exposition of the candidates for Arnolfini and his wife, none of whom are a good fit in terms of date and marital status.[3] Without a doubt, Kemperdick’s discussion opens up many questions on Van Eyck’s portrait projects and on the changing ways art was amassed and described in the nascent collecting culture of the sixteenth century. Already within this catalogue, in his entry on the Man Holding Pinks (no. 12) painted about 1520 using a lost Eyckian portrait as a model, Kemperdick considers that this painting is a re-conception of its fifteenth-century model as a mocking genre figure of an amorous older man.

This catalogue will be indispensible for those seeking authoritative information on Berlin’s extraordinary collection. And it has a broader use, since it traces the arc of the period and will be mined as a source of new directions concerning artistic personalities, painting techniques, patronage, and object types.

Martha Wolff

Independent scholar

[1] Los inventarios de Carlos V y la familia imperial, ed. Fernando Checa Cremades, vol. 3, Madrid, 2010, pp. 2391, 2484.

[2] Marco Paoli, Jan van Eyck alla conquista della Rosa. Il Matrimonio ‘Arnolfini’ della National Gallery di Londra: Soluzione di un enigma, Lucca, 2010, pp. 24-26.

[3] Lorne Campbell, National Gallery Catalogues: The Fifteenth Century Netherlandish Paintings, London, 1998, pp. 174-211.