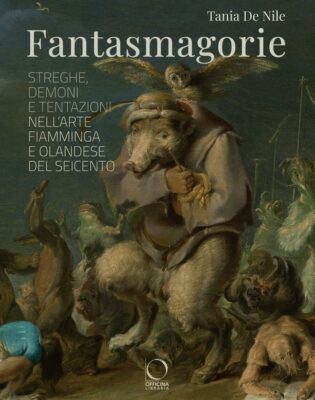

The European fascination with the various manifestations of witches, demons and evil temptations seems endless; it generated a flourishing production of imagery that was supported by literary culture. As a byproduct of Christian morality and the opposition of heaven and hell, evil and its aberrations would seem to attract more interest than the calm of earthly and celestial paradise. Consequently, infernal scenes proliferated during the Renaissance and well beyond. Tania De Nile has systematically charted the course of demoniacal imagery from Hieronymus Bosch through the seventeenth century in the works of north and south Netherlandish artists, and demonstrated how artists distinguished their own production from their predecessors and contemporaries. The international arena for their imagery extended from the Netherlands to Spain and Italy, indicating the mobility of paintings, prints, and artists, and the exchange of visual references.

At the outset, the author establishes the term spoockerijen as it appears in seventeenth- century artistic literature, inventories and auctions to indicate a precise category in the figurative culture of the Low Countries. The art market, publishers, collectors and artists promoted these subjects. The spoockerij involves what is imagined and concerns the visionary, demons, inferno, and temptations of saints; it contrasts with visible reality, perceived or credible. Witchcraft, considered anti-Christian and evil, was conflated with devil worship, and took various forms in regions of Europe. If those accused of witchcraft may now be recognized as persons on the margins of society, such was not the case in earlier centuries. The witches’ gathering persisted in this imagery from 1450 to 1800, and in behavioral, legal and punitive aspects of society.

Chapter One highlights Hieronymus Bosch, who is recognized as the inventor of the fantastic by Lodovico Guicciardini (1567) and the creator of devils by Marcus van Vaernewijck (1566). Literary precedents and their imagery include the Apocalypse, the Divine Comedy, Visions of Tondal, and the Malleus Maleficarum. Bosch favored the sinister, as in the tree-man motif (fig. 230), and his paintings were imitated soon after his death. He is followed by Pieter Bruegel, who is called “the second Bosch” by Guicciardini and Domenicus Lampsonius (1572). His son Jan Brueghel painted inferno scenes, and this specialty continued into the next generation.

In Chapter Two, De Nile traces the intellectual and literary background of infernal imagery from antiquity through the Baroque. The theme of devils is hard to define as a single category of art production or in the historiography. Karel van Mander, citing Pliny, recognized that artists need not specialize in the four main genres of histories, landscape, still life, or portraits, but could excel in another, more specific category, as “animals, kitchens, fruit, flowers, landscape, architecture, cartouches, perspectives, nocturnes, fires, portraits from life, marines or some other kind of painting.” (51) In recognizing the chromatic range of flames, vapors and smoke, Van Mander relates fires to Vulcan, Styx, the ferocity of Cerberus and the Hydra, and spoocken; he refers to paintings by Bosch, Bruegel, Jan Brueghel, Hans Vredeman de Vries, Carel van Yper, Bartholomeus Spranger, Jan Mandijn and Frans Verbeeck, among others. Franciscus Junius, citing Cicero, proposed that the knowledge of reality is attained through the senses, through simulacre, and these may be spectra, as specters of the imagination or fantasy (55). Junius echoes Horace who condemned artists who created monstrous imagery. Building upon Junius and ancient rhetoric, Samuel van Hoogstraten (1678) went further in decrying artists who paint frightful monsters and trifling subjects. For Gerard de Lairesse (1707), who valued verisimilitude, order and beauty, the painting of monsters and imaginative scenes overstepped all limits of decorum. However, he recognized that the representation of dreams necessitated specters of the supernatural. As a biographer, Arnold Houbraken (1718) called David Rijckaert III “a second Brueghel of hellish scenes.” He considered spoockerijen as a category of painting, listing Cornelis Saftleven, Gerrit van Spaan and Pieter Fris among its practitioners. Hellish paintings were popular in both the northern and southern Netherlands, as indicated by a tabulation of documents from seventeenth-century inventories and auctions; 230 representations occur in Antwerp sources and, in the North, 209 in Amsterdam, Delft, Dordrecht and elswhere.

Chapter Three proposes a theory of the fantastic, using sources from antiquity and the Renaissance, and imagery often based on ancient literature. De Nile analyzes how Plato, Aristotle, Macrobius, Daniele Barbaro, Anton Francesco Doni, and Gabriele Paleotti treat imagination as a source of representation, with various degrees of unreality; my summary greatly simplifies her presentation, which is rich in literary and pictorial references. Connections between dreams and artistic imagination give rise to ghosts, night creatures, demons, and hybrid and unformed beings. Homer and Ovid give large roles to dreams and sleep. For examples, in Homer (Odyssey Book XIX), Penelope voices positive and negative alternatives that appear in her dream. In Ovid (Metamorphoses Book XI), the apparitions of Morpheus take shapes both human and hybrid in the dark underground House of Sleep.

In Chapter Four, De Nile examines phantasmagorical prints that circulated among artists and collectors. Although the engravings after Bruegel’s Seven Deadly Sins and other subjects may be familiar, they are preceded and followed by a plethora of printed temptations, hybrid creatures and witchcraft scenes. The printmakers involved range from Martin Schongauer to Jacques Callot. Their prints are adapted in paintings by David Teniers II and Joseph Heinz the Younger. One much-repeated figure is the witch with hair streaming forward in the wind, who appears in an engraving by Jan van de Velde II (1626), possibly after Adam Elsheimer (fig. 148). De Nile concludes the print tradition with Francisco da Goya.

The longest chapter is the fifth, which demonstrates that representations of the underworld, sorcerers and demons formed a large part of the production of select artists during the seventeenth century. By the 1590s, Jan Brueghel the Elder in Rome and Milan (until 1596) and Jacob van Swanenburg in Naples (until 1616), had established their specialties in underworld imagery. Brueghel would return to Antwerp in 1596 and paint only a few hellish scenes thereafter, but these held an enduring fascination for artists and collectors.

Jacob van Swanenburg, drawing upon Brueghel, Marten de Vos, and Jan van der Straet (Johannes Stradanus) developed his own underworld inventions; these would impress artists active in Italy, including Belisario Corenzio (Punishment of the Damned, drawing, Uffizi, 1603-1605; fig. 249) and Filippo Napolitano in Naples and Florence (figs. 251-254). Swanenburg adapted his signature winged vessel from Pedro Rubiales’s Last Judgment in the Castel Capuano, Cappella della Sommaria, Naples (1548-1550; fig. 245), who borrowed it from Michelangelo’s Last Judgment (Sistine Chapel). In 1608, Swanenburg came before the Inquisition in Naples for showing a suspect painting outside his shop to interested crowds; he managed to talk his way out of the accusation of heresy by stating that he copied the figures of devils from an Italian artist’s altarpiece in Monte Oliveto (200). In fact, in an earlier painting he also copied figures of flying women from an anonymous etching of 1593 representing witches and necromancers (figs. 231-232). Some of this material on Swanenburg appeared in a book chapter by the author entitled “Rethinking Swanenburg: The Rise and Fortune of New Iconographies of the ‘Hell’ in Italy and the Northern Netherlands,” (Marije Osnabrugge, ed., Questioning Pictorial Genres in Dutch Seventeenth-Century Definitions, Artistic Practices, Market & Society, Turnhout: Brepols 2021, 291-309).

Concurrently, Jacques de Gheyn II, then based in Leiden, made over a dozen drawings concerning witches, of which the most elaborate was engraved by Andries Stock (c. 1610; fig. 228). The background to De Gheyn’s interest and subjects includes earlier prints and Reginald Scot, The Discoverie of Witchcraft (London 1584), translated by Thomas Basson as Ontdecking van tovery (Leiden 1609). Scot’s premise was controversial; he proposed that those so-called witches were not affected by the devil, but rather by strange visions and illusions more associated with melancholy. His ideas were met with sympathy among Leiden scholars (196). Familial connections strengthen this association, as Thomas Basson’s son, Govert, married De Gheyn’s sister Anna in 1608. De Gheyn may have associated sorcery with melancholy, but nonetheless also associated it with witches’ sabbaths, thus blending Scot’s psychological explanations with more sinister ones.

Later in the century, Salvator Rosa, Cornelis Saftleven, David Teniers II, David Rijckwaert III and Domenicus van Wijnen explored fantastic imagery, each following his own inclination. The popular subject of the Temptation of St Anthony elicited a variety of approaches, indicating a certain freedom in representing the imagined.

This volume is a masterful survey of the imagery and literary background of fantastic evils, necromancy and underworld themes that form the category of spoockerij.

Amy Golahny

Boston College

Richmond Professor of Art History Emerita, Lycoming College