In his introduction explaining the organizing principles of this catalogue raisonné, José Juan Pérez Preciado discloses a crucial detail about the fifteenth-century Netherlandish paintings in the Prado’s collection: not a single work is signed by the artist or artists who painted it. While perhaps self-evident to many, this fact bears repeating to demonstrate what a monumental undertaking it is to catalogue the products of artists who worked anonymously and collaboratively, and who understood authorship in ways entirely different to today. Indeed, what makes this volume so remarkable is its commitment to exposing and confronting the many challenges of such an endeavor: the lacunae in the material and archival records, the history of countless misattributions, the geopolitical dynamics informing the history of attribution, not to mention the often revelatory advancements in imaging technology that inform connoisseurship today.

The volume starts with two thematic essays that seek to establish a new methodological foundation for the field, one that embraces how circumstantial our understanding of fifteenth-century painting is and acknowledges how much we must learn and unlearn from a historiography that has too often sought concrete answers. The first of these, Lorne Campbell’s foreword, takes the reader to the field’s origins around 1400. Crucially, as Campbell notes, Netherlandish painting was never a completely independent and stable genre. Paintings were not understood as an isolated medium, since they almost always moved through the European craft economy in conjunction with sculpture, tapestry, stained glass, and drawings. Patrons, artists, and courts were all itinerant. The earliest contracts written in Spain for commissions of Netherlandish paintings are vague about geography, the status of painting, and the identity of the painter. For example, in the 1443 commission of an altarpiece for the chapel of Casa Municipal of Zaragoza, it is a sculptor – Pere Joan – who is tasked with overseeing the production of the painted wings as well as the carved central image. Moreover, there is no mention that the wings should be painted in the “Netherlandish” style; the technique of oil painting that artists from the Low Countries are traditionally credited with inventing is simply described as “new.” With that statement of newness, the historiography of Netherlandish painting began, having little to do with the works themselves and more to do with what they were defined against.

Preciado’s essay continues in this historiographical mode by considering how the uncertainties and ambivalences inherent to Netherlandish painting have continually posed problems for interpreting and displaying the Prado’s collection. In the decades after the museum’s opening in 1819, these artworks were something of a mystery. Entering the collection as unattributed, most were soon seen as German – essentially a catch-all term for that which did not appear Italian or Spanish. Gradually, they started to be organized around artists’ names known from the pages of royal inventories: Bosch, Bruegel, Dürer, Gossaert, and Holbein. As the Prado’s collection expanded with paintings from the monastery of El Escorial (1839) and from the Museo de la Trinidad (1872), the latter of which housed works expropriated from Spain’s churches in the 1830s, so too did cataloguing efforts. According to Preciado, one of the main impetuses for this was not the growing number of works but the spread of their international reputation, especially after Johann David Passavant’s visit in the mid-nineteenth century, when a wide array of European professors and curators began studying the collection and weighing in on attributions. This flurry of connoisseurship may have been a disservice to the collection, further splintering it into a series of familiar names versus unknown masters – an inconsistent kind of methodology that seems to reflect more the rise of the itinerant tourist-scholar than anything about the actual works. By the time the paintings had their first dedicated space at the Prado around 1900, the only organizing principle was that all were done on panel and were older than most other things in the museum. A hang by school – made possible by new efforts to rethink attribution more systematically – did not occur until 1933, over a century after the museum opened. The galleries’ organization today still is largely based on this framework.

Preciado then introduces the catalogue portion of the volume. Again with a sensitivity to historiography, he situates his undertaking within that lineage and foregrounds how the book’s structure is informed by both personal choice and logistical necessity. The catalogue’s scope, he states, encompasses the products of fifteenth-century Netherlandish artists, as well as works by artists who were active in the sixteenth century but whose relationship with the previous century is “unquestionable.” For example, Albrecht Bouts is included because he repeated certain religious motifs introduced by his father, Dirk. Gerard David is included because of his status as the purported “last” early Netherlandish painter and, more importantly, because many of the paintings catalogued in the volume were previously attributed to him. Though not explicitly stated, the unifying element seems to be the Gothic. The Prado’s lone fifteenth-century French painting – The Agony in the Garden of ca. 1405-11 (cat. 44, acquired in 2012) – is included on such stylistic grounds, whereas Netherlandish proto-Mannerists like Ambrosius Benson, Albrecht Cornelis, and Adriaen Isenbrant are not. Hieronymus Bosch is also not treated in this catalogue because of “the unique nature of his pictures, which foreshadow sixteenth-century art” (45), and because of the extensive scholarship already devoted to him in recent Prado publications.

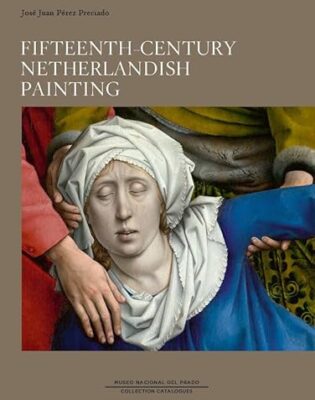

The volume proceeds with entries on forty-four paintings. Some, like that for Rogier van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross (cat. 41), are refreshingly concise; others, like that for The Fountain of Grace by Jan van Eyck’s workshop (cat. 15), are enthrallingly complex and reference the painting’s links to Northern sculpture and silverpoint drawing as well as to Spanish manuscript illumination, such as Moses Arragel’s Alba Bible. Entries on paintings with still uncertain attributions are particularly compelling for how they embrace ambiguity and offer a more expansive view of authorship. The Saint Monica panel by an unknown follower of Dirk and Albrecht Bouts (cat. 9), for example, initially appears to be a reverse copy of the Mater Dolorosa at the National Gallery, London (NG711). Yet through Preciado’s careful contextualization of the iconography’s widespread circulation and his insightful analysis of the copyist’s technique and subtle departures from the original, the act of copying emerges as a generative kind of artistic act. The discussion of Rest on the Flight into Egypt (cat. 11) – long attributed to Gerard David’s workshop and considered a lesser version of the painting at The Metropolitan Museum (49.7.21) – also challenges entrenched notions of original versus copy. Preciado argues that neither painting is exactly original, since both derive from distinct but related models originating in David’s workshop. Although The Met’s version may have been made by a more skilled hand, that artist – much like whoever was responsible for the Prado’s painting – still based their composition on and honed their technique through a highly collaborative and iterative workshop practice.

Entries adhere to a format echoing other recent systematic catalogues like the London National Gallery’s, though they incorporate several innovative and highly useful features. The front matter for each entry includes references to known copies and versions of the painting under discussion, as well as mentions of it in prior Prado catalogues, thus enabling readers to trace histories of attributions and interpretations with ease. Other highlights are the concise artist biographies that preface entries for works by identifiable masters. These biographies provide a map of canonical sources and important passages by scholars like Passavant or Max J. Friedländer, and Preciado has added his own reference points by calling attention to works that anchor the discussion: key paintings in the artist’s oeuvre; paintings previously attributed to the artist that might appear elsewhere in the catalogue under a different name; as well as works that may have been sources of inspiration for the painting addressed in the entry that follows. For instance, Albrecht Bouts’s biography notes that the artist was a sacristan at Leuven’s chapel of Our Lady Outside the Walls when Van der Weyden’s Descent was still on view there. The biographical text on Petrus Christus connects him to paintings by Van Eyck in Detroit and at the Frick that he is believed to have completed. These thoughtful reminders appear throughout the object entries’ prose as well, and I know they will be immensely useful for many, including myself, because of the way they constantly prompt one to consider the comparisons upon which the field and its understanding of authorship is based. It is almost as if the catalogue is organized to provide each reader with the modern tools of connoisseurship, thus inviting all of us to rise to the task of exploring the endlessly complex and self-referential nature of Netherlandish painting. This volume will thus be an indispensable volume for students, professors, museum professionals, and interested readers alike.

Andrew Sears

National Gallery of Art