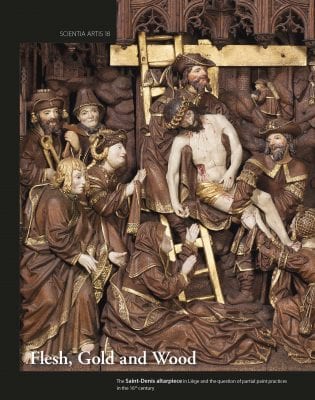

This book contains twenty articles (about half in English and half in French, all with English abstracts) from a 2015 international symposium held at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) at Brussels. The symposium marked the conclusion of the Institute’s 2012-2014 restoration of the St. Denis Altarpiece in Liège. This sculpted wooden altarpiece, one of the largest in Belgium, has long held scholarly interest because of its links to the Borman school of sculptors in Brussels and to the Liège painter, Lambert Lombard. The stylistic and iconographic disparity between the work’s case and its predella – the case has a standard Passion cycle and a more Gothic style, whereas the predella has an atypical depiction of the life of St. Denis and a more Italianate style – has also attracted attention and raised questions about the work’s patronage and production. This new publication, which has an unusual cohesiveness and structure compared to most conference proceedings, demonstrates the power of scientific studies, working in concert with art historical research, for making critical advances in understanding major works of art. While not solving every question, the scientific analysis furnished stunning new discoveries, above all, confirmation, for the first time, of the practice of partial polychromy within the Netherlandish carved altarpiece tradition. In addition, the technical analysis also confirms that the predella was produced at the same time as the case, supporting the theory that the work was fully commissioned and accommodated to sixteenth-century tastes for artworks mixing Gothic and Italianate styles.

The book opens with Pierre-Yves Kairis’s study of the historical context, which situates the altarpiece within the orbit of its purported patron, the Prince Bishop of Liège, Érard de La Marck. Kairis discusses Érard’s frequent patronage of art works marked by Italianism but still rooted in Gothic traditions, as well as his political turn away from ties to France to the Holy Roman Empire, and his patronage of German sculptors. Thus he articulates the conditions that likely fostered the choice of partial polychromy in the Liège altarpiece, that is, the use of polychromy only for the flesh areas, with small areas of decorative gilding on the costumes.

Emmanuelle Mercier’s following article provides the main technical results from the altarpiece’s conservation. Her essay includes evidence that large sections of the work (mainly the architectural decoration and the robes of the figures) were originally intended to be unpolychromed, so they were not left bare due to delay or to later stripping of the polychromy. Specifically, the conservators determined that the bare wood in the unpainted sections was covered with benzoin resin, a finish never used in polychromed altarpieces, but which is similar to the materials used in German altarpieces designed to remain unpolychromed. Lack of dust below the resin layer indicates that the resin was applied at an early stage. Mercier also presents physical evidence that the predella was made at the same time as the case (the joins in the two sections show similar construction) and that the predella does not date after the case as previously thought (dendrochronology establishes that the predella’s trees were even felled before those of the case). A critical piece of evidence adduced here is the use of Liège measurements for some elements of the case, which allows Mercier to argue convincingly that the Liège Altarpiece represents a commissioned production, not customization of a ready-made product.

Other essays explicate more details from the conservation and scientific analysis. Of special note here is Pascale Fraiture’s dendrochronological results, which reveal that the altarpiece includes architectural ornament made from trees not of Baltic origin, like the rest of the work, but from trees closer to Liège, thereby supporting the case for production, at least in part, in Liège, as well as the commissioned nature of the project. In addition, many of the essays examine more fully the roles of the Bormans and of Lambert Lombard. Catheline Périer-D’Ieteren’s contribution associates the sculptures of the altarpiece’s case with Jan III and Passier Borman’s work at Güstrow; Michel Lefftz also considers the predella to be a product of the Borman shop as well, and argues that it demonstrates the late Borman shop’s ability to work in a Gothic Renaissance style similar to that in their altarpieces in Lombeek, Bonn, and Brou.

The volume includes a useful pair of essays treating the altarpiece’s little-known painted wings, now partially missing and separated from the sculpted center. Dominique Allart concludes that the wings of the case and predella were produced by two separate ateliers in an antique-influenced style as a collaborative production under the direction of, but with little direct participation by, Lambert Lombard. Further claims for local production are supported by the presence of Liège measurements in the squaring found in one underdrawing (also discussed by Claire Dupuy and Dominique Verloo). The attribution to Lombard’s direction of the entire production is further supported by the documentation of a very large payment to “Lambertus pictor” in 1533, discussed more fully in Emmanuel Joly’s essay.

The second half of the volume shifts the focus on placing the Liège Altarpiece in a broader context. While some essays concentrate on individual works of art – notably those by Ria De Boodt, Brigitte D’Hainaut-Zveny, Julien Chapuis, Dagmar Preising, Michael Rief, and Barbara Rommé – most consider the Liège Altarpiece within the larger phenomenon of partial polychromy. They assess partial polychromy in different regions and considering different reasons and meanings associated with its use in different media. The authors advance various theories for the use of partial polychromy in the Liège Altarpiece, including: the influence of antique values; new concepts of space; reformist religious tendencies; the desire for greater legibility; aesthetic preferences; and the desire to emphasize flesh – and thereby the doctrine of Transubstantiation. The final contributions, which explore the specific context of polychromy in Gothic alabasters (Kim Woods) and monochromy in Italian Renaissance art (Marco Collareta), round out a strikingly successful joint project that represents a wonderful contribution to the study of Late Gothic sculpture.

Lynn F. Jacobs

University of Arkansas