Twenty years ago, in 1998, Maximiliaan Martens, Paul Huvenne and Valentin Vermeersch organized a seminal exhibition at the Memlingmuseum in Bruges, “From Hans Memling to Pieter Pourbus” (the catalogue appeared as Bruges and the Renaissance: Memling to Pourbus). This groundbreaking study focused primarily upon a relatively neglected period of Bruges art history, the sixteenth century (Memling and Gerard David, the only fifteenth-century artists in the show, belonged to the older, privileged Bruges art of the “Primitives”). The title did not fully define the ambitious scope of the exhibit, however, for extending beyond the career of Pourbus the show also included works by Pieter II and III Claeissens, and Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder.

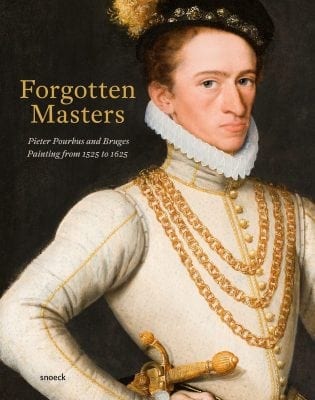

The present exhibition catalogue, Forgotten Masters, covers many of the same sixteenth-century Bruges artists, commencing with Adriaen Isenbrant and Ambrosius Benson, and it adds to the roster of end-of-century artists the figures of Gillis Claeissens, Antonius Claeissens, and Frans II Pourbus. Between these two catalogues there is now a wealth of information and a thorough, modern analysis of Bruges art during the long sixteenth century. Forgotten Masters provides a far more robust investigation of the mid- and late-century milieus. As in 1998, however, Pieter Pourbus is the uncontested hero. Forgotten Masters, naturally, incorporates a new reliance upon findings from technical studies of individual works, above all the underdrawings. Built upon these technical results, along with the scholarship since 1998 and the research carried out for the exhibit, many older attributions are revised and new ones are proposed or substituted.

The catalogue’s first two essays, one by Heidi Deneweth and Ludo Vandamme and the other by Brecht Dewilde, together furnish a nuanced reading of Bruges’ slow, if uneven, decline during the sixteenth century. Although the number of painters active in the city peaked in the 1520s, until around 1545 there were still 45-50 painters at work. But from that point the drop-off was precipitous: down to 28 in 1575, and a mere 10 in 1600. Successful strategies early in the century to develop new markets in the face of diminishing demand focused on spec painting for the open market (including the pandt market), on subcontracting, on outsourcing for rapid production (e.g., in the work of Jan van Eekele), and on redoubling efforts to increase art exports, especially to Iberia. The early work of Pieter I Claeissens was particularly geared toward the Spanish market. This output included his use of a unique Latin signature on several paintings, spelling out not simply his name and home in Bruges but also giving his street address, thus directing potential buyers to his studio’s location (cat. nos. 8, 9, 16). By mid-century, however, the pandt market was shrinking and competition from Antwerp for exports to Spain had become fierce, so the work of Pieter Pourbus and his contemporaries shifted much of the focus to local buyers and institutions. There too, however, demand was eroding, and some artists had to diversify by taking on supplementary work, such as mapmaking and print illustrations, as Van Mander recorded in his life of Marcus Gheeraerts (which he spells “Geerarts”).

In the essay by Dewilde and Anne van Oosterwijk on the Claeissens families’ oeuvres, the main effort is to clarify the work of Pieter I and Gillis Claeissens, which is greatly abetted by recent scholarship. The work of Pieter Pourbus is addressed in multiple essays, including a detailed overview of his life, career and importance by Paul Huvenne, who has studied the artist for many years; plus an essay by Anne van Oosterwijk and Margreet Wolters that investigates the role of underdrawings in his oeuvre, and in the work of Pieter I and Antonius Claeissens.

Anne van Oosterwijk additionally contributes an incisive essay on Pourbus’s Bruges patrons. In this context she reexamines the remarkable documentation that survives for his work; namely, contracts for three of his paintings; preparatory drawings for five extant paintings; and the vidimus (contract drawing) for his Van Belle Triptych (cat. 32), including the patron’s annotations for the corrections he wanted. Essays on Bruges painters and rhetoricians (by Samuel Mareel), on Pieter Pourbus and the Claeissens’s family in relation to Iberia (by Didier Martens), and on artists’ migration from Bruges (by Brecht Dewilde) round out the nine catalogue essays.

Dewilde generated a statistical database from which he was able to track the numbers of artists leaving Bruges by decade, and to identify the two key periods of migration: 1505-1523 and the 1560s to 1590s. In phase one, most artists left Bruges to relocate to Antwerp, which was then enjoying explosive commercial growth. While that motivation was unquestionably economic, in phase two, when most artists resettled in foreign lands, the departure impetus was apparently to escape the devastating religious conflicts in the Low Countries.

Unlike sixteenth-century Antwerp, where a principal engine of art production was the development of new pictorial genres, as Larry Silver demonstrated in his 2006 Peasant Scenes and Landscapes, in Bruges an essential characteristic of creation was the recycling of local artistic models from the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. Maximiliaan Martens had drawn special attention to this phenomenon in 1998, and the present exhibition adds many new examples of this deeply entrenched civic impulse. To cite a few instances: Pieter Pourbus’s 1557 Crucifixion (cat. 33) is predicated upon Eyckian models; Pieter I Claeissens’s St. John on Patmos (cat. 9) is based upon the right wing of Memling’s St. Johns Altarpiece in the St. John’s Hospital; the Ontañada Madonna by Gillis or Pieter II Claeissens (cat. 51) reverts to Gerard David’s images of Mary offering the Christ Child on her lap a bunch of grapes; Ambrosius Benson’s Deipara Virgo (cat. 2) is based upon a Simon Bening miniature; and Pieter II Claeissens recycles both Isenbrant’s Immaculate Conception (cat. 52) and Isenbrant’s Magdalene Reading (cat. 56).

All the contributors to this essential catalogue deserve kudos for the high level of their work, especially Anne van Oosterwijk and Brecht Dewilde for their multiple contributions. This publication ensures not only that these Bruges artists will no longer be forgotten, but also that they can now be apprehended with far more precision and insight than was heretofore possible.

Dan Ewing

Barry University