In 1548, early in his printing career, Christophe Plantin left Paris for the greater opportunities and resources of Antwerp. There, he established one of the leading printmaking and publishing houses in Europe, located strategically on the old commercial square of the Vrijdagmarkt, adjacent to the city’s commercial nexus of Cathedral square and Groenplaats, harbor, Grote Markt, and Our Lady’s Pand. His assistant, later his son-in-law, Jan Moretus, took over the business upon Plantin’s death in 1589.

This exhibition is dedicated to showcasing the beautiful, important drawings that have been collected by the Museum Plantin-Moretus since its founding in 1877, in the historic buildings on the Vrijdagmarkt. Of the eighty Flemish, mainly Antwerp drawings from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in the show, fifty-five works are from the Plantin-Moretus collection. They are supplemented by additional drawings from other Belgian collections. As Virginie D’haene, drawings’ curator at the Plantin-Moretus and catalogue editor explains in her Introduction, in 2018-19 many drawings in the Plantin-Moretus’ collection were placed on a List of Masterpieces by the Flemish government, conferring special protections and a new status. This prestigious designation motivated this exhibition, organized to shine a light upon these exceptional works.

Fifty-four of the eighty drawings in the exhibition are seventeenth-century pieces. This is hardly surprising given the greater survival rate for drawings from the seventeenth century than from the sixteenth century. For the former, the greatest representation is drawings by the Antwerp triumvirate of Rubens, Jordaens, and, to a lesser degree, Van Dyck. Though somewhat jarring for those still accustomed to Jacob as his forename, Jordaens is rightly referred to here by his birth name, Jacques. This is the name he used to sign his paintings and to sign letters he wrote in Flemish, his native tongue.

The method of the catalogue, as explicated in D’haene’s Introduction, is to focus primarily upon the function of the drawings, separate from their stylistics, techniques, provenance, etc. Each of the three catalogue essays addresses a different aspect of drawing function, which the individual drawings catalogued after each essay illuminate. In Part I, Sarah Van Ooteghem analyzes study drawings. These are drawings as the starting point of apprenticeship training, followed by the lifelong practice of drawing to sharpen and increase skill through observations of daily life (genre scenes and naer het leven studies), landscapes and nature scenes, living models, and tronies.

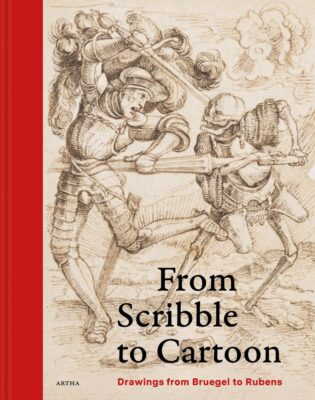

Another important category of study drawings is the copy drawing, used to learn from other masters. Though such drawings are typically the foundation of apprenticeship, they also often continued to be made throughout the artist’s career. The first drawing in the catalogue is, appropriately, a copy drawing by Rubens of Holbein’s The Knight and Death (cat. no. 1), from the latter’s Dance of Death woodcut series. This group of Rubens copies constitutes the artist’s earliest known works, created probably during his apprenticeship, around age thirteen. This particular Holbein image is singularly dramatic and well known; and Rubens’s copy of it brackets the two centuries of the exhibition. The decision to open the catalogue with it, and to use it as the cover image, is thus especially fitting. Other famous Rubens copies in the show are his beautiful drawing of the Gemma Tiberiana cameo (no. 6) and the Belvedere Torso (no. 7). Jordaens’s handsome chalk tronie of an old woman’s expressive face (no. 11) is complemented by his even more remarkable observational drawing of five women chatting in the street during an Antwerp uprising (no. 13). Still other observational drawings include Joannes Fijt’s growling dog (no. 16) and several seventeenth- and sixteenth-century landscapes, including a beautiful country village drawn by Bruegel around 1554 (no. 23). One of the most extraordinary sheets of the entire exhibition, however, is the remarkable, albeit anonymous, rendering of a dead fin whale, belly-up, which in 1547 was stranded on the beach in Egmond (no. 15). It is shown to dramatic effect in isolation, as denizens of the town and a contingent of Benedictine monks clamber upon the hapless animal. The large size of the drawing, 81.5 cm wide, necessitated gluing together two sheets of paper to enable its impressive scale.

In Part II, D’haene considers design drawings, that is, drawings made to work out the conception and details of a planned new work (preparatory drawings). Such drawings were made by painters for future paintings, by sculptors for sculptures, and by artists for all manner of works, such as designs for prints, book illustrations, ceiling decorations, painted glass roundels, Joyous Entries, and so on. Examples of each of these, and many others, are highlighted. Principally, though, D’haene’s essay focuses upon deconstructing the progressive stages of design drawings. The first stage is often a scribble (crabbelinge, as in the catalogue’s title), a quick, minimal sketch. Next is the modello or patroon, a more finished conception, typically larger in scale, and often submitted to the patron to obtain the commission. Closely related is the vidimus or contract drawing, a highly finished work for the patron’s approval. Transfer drawings – pricked and pounced or squared for transfer – are a later stage; followed by the full-scale, final drawing, the cartoon (as in the title).

The sole scribble in the exhibition is Rubens’s rapid, loose sketch of his initial conception for The Last Communion of St. Francis of Assisi (no. 25), the painting now in the Koninklijk Museum, Antwerp. Relatively few such scribbles survive (but see the discussion of Johannes Stradanus’s corpus of scribbles, p. 100). Among the other design drawings in the catalogue, particularly notable are Maerten de Vos’s drawings of personifications for the 1594 Joyous Entry of Archduke Ernest of Austria into Anwerp (no. 35); a handsome drawing for two towel racks and three firedogs by Paul Vredeman de Vries (no. 38); an Antwerp Mannerist chiaroscuro drawing for a glass roundel, one of the earliest sheets in the show (c. 1520-30, no. 50); Rubens’s design for a lost silver plate decorated with the “The Golden Compass” printer’s mark of Plantin’s publishing house (no. 57); and an elegant drawing for a holy water font attributed to Artus Quellinus II (no. 58).

In Part III, An Van Camp addresses independent drawings, a new kind of drawing that emerged in the late fifteenth century, especially in Italy though also in Dürer’s art. Such drawings were made for sale on the market, or for gifting, or made simply for the act of drawing. She enumerates many categories, including presentation and gift drawings, friendship drawings, alba amicorum, drawings for special occasions (weddings, coronations, etc.), and landscape drawings, among others. One of the most outstanding examples of a drawing in an album amicorum is Rubens’s Crescetis Amores (Venus Nursing Three Cupids, Antwerp, Private collection) for his friend Paulus van Halmaele, a lawyer who held important public positions in Antwerp (no. 71).

Her second featured example is especially significant for an exhibit focused mainly on Antwerp art. These are the twenty-eight pages of whimsical, inventive, grotesque initials drawn by Cornelis Floris II in the margins of the Liggeren, the hand-written membership and apprentice ledgers of the Antwerp St. Luke’s guild, one of the most complete art-guild documents of the period in the southern Netherlands, rendered doubly exceptional by these witty embellishments (no. 66). No less extraordinary are the 98 illustrations by Lucas d’Heere for his Théâtre de tous les peuples et nations de la terre…, a manuscript of ancient and contemporary clothing modes throughout much of the world and history (no. 67). An exquisite friendship drawing by Joris Hoefnagel (no. 70) is inscribed “to Mr. [Abraham] Ortelius in the year 1593 as a monument of their friendship, with his genius as a guide.” The exhibit also includes a famous, very beautiful and meticulously executed pen drawing on vellum of Apelles Painting Campaspe by Johannes Wierex (no. 72, and frontispiece to title page), who seems to be the first Antwerp artist to introduce this drawing technique on parchment. Highly regarded, such works were often glued to wooden panels, framed, and hung on walls.

This summary of some of the exhibit’s highlights, it is hoped, will convey something of the treasures that await the reader of this handsomely produced catalogue. The exhibition organizers have admirably succeeded in their stated goal of bringing attention to “the exceptional quality and value” of the newly designated “Masterpiece” drawings in the Museum Plantin-Moretus.

Dan Ewing

Barry University

Bruegel to Rubens. Great Flemish Drawings. By An Van Camp [Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford, March 23 – June 23, 2024]. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, 2024. 244 pp, fully illustrated in color. ISBN 978-1-910807-59-0.

The catalogue of the second venue, the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology, Oxford, titled Bruegel to Rubens. Great Flemish Drawings is written entirely by An Van Camp, Christopher Brown Curator of Northern European Art. It consists of five essays – definition of drawings, materials and tools, purpose (copies), categories (portraits and landscapes), function (prints, sculpture, tapestries), independent drawings – , illustrated with the drawings in the exhibition, followed by a checklist of exhibited works but no full entries.

Not all drawings shown in Antwerp traveled to Oxford, e.g., the anonymous Fin Whale, specifically referred to above (no. 15); Cornelis Floris II’s grotesque initials in the Liggeren of the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke (no. 66); Lucas d’Heere’s costume studies (Théâtre de tous les peuples et nations de la terre…, lent by the university library, Ghent, no. 67); or Johannes Wierix’s beautiful drawing on vellum, Apelles Painting Campaspe (no. 72), but the Oxford showing includes 48 sheets not exhibited in Antwerp from the holdings of the Ashmolean Museum, Christ Church and the Bodleian Libraries, among them Rubens’s Portrait of Arundel (no. 27), his study of a Male Nude Torso for the Antwerp Raising of the Cross (no. 37), The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes from Christ Church (no. 67) and the beautiful late Woodland Scene in the Ashmolean (no. 110). The exhibition also includes two grisaille sketches by Rubens in the Ashmolean of St. Barbara and St. Clara of Assisi for the Antwerp Jesuit church ceiling (nos. 84, 85). More liberally represented in Oxford than in Antwerp, Van Dyck’s drawings are supplemented with his Study of a Man with Arms Crossed (recto) and a Right Arm (verso) (no. 40), Portrait of Justus van Meerstraeten (no. 41) and Studies for Prince James as a Child (no. 42), the latter two lent by Christ Church. However, Van Dyck’s early sketch, The Expulsion from Paradise (Antwerp, no. 26), did not make it to Oxford.

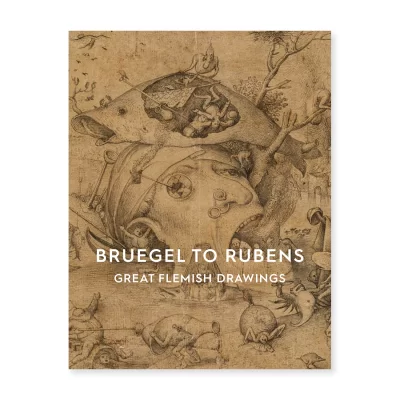

Among sixteenth-century drawings, most outstanding is Pieter Bruegel’s Temptation of St. Anthony for the engraving by Pieter van der Heyden (no. 51), also chosen for the cover illustration. Among Rubens’s designs for book illustrations and title-pages, the recently acquired Elderly Scholar Disguised as Atlas Supporting a Sphere on His Shoulders for Franciscus Aguilonius, Opticorum libri sex was shown in Antwerp and Oxford, whereas the design for the title-page of Bauhuis and Cabilliau, Epigrammata/ Malapert, Poemata, exhibited in Antwerp (no. 43) was exchanged for the title-page to Balthasar Cordier, Opera S. Dionysii Aeropagitae, I, engraved by Cornelis Galle I, from the Ashmolean (no. 61). Another scene designed for a print included in Oxford is David Vinckboons’s lively Beggars Inn, engraved by Pieter Serwouters (no. 65).

In several instances thematically or technically related drawings by one artist in either collection are brought together, such as Joris Hoefnagel’s Allegory for Abraham Ortelius from the Plantin-Moretus and Flowers in a Vase with Insects from the Ashmolean, a fine example of Hoefnagel’s miniature watercolors on vellum (nos. 101, 102), or Jan Boeckhorst’s Apollo and Artemis Killing Niobe’s Children in Antwerp and Apollo and the Muses from the same tapetry cycle in the Ashmolean (nos. 96, 97).

Considering the difference in the selection of drawings and in the makeup and content of the two catalogues, including the essays by An Van Camp in the Oxford version, it is advisable to consult both publications.

Kristin Belkin