This welcome book by an established scholar of artistic relations between Urbino and the Netherlands is the first monograph on Justus of Ghent since Jacques Lavalleye’s of 1936. Since then, many theories have been propounded on Justus’s oeuvre and identity, enriched by scientific research, notably Nicole Reynaud and Claudie Ressort’s revelation that many of the Famous Men in the Louvre were extensively reworked by a second artist (“Les portraits d’hommes illustres du Studiolo d’Urbino au Louvre par Juste de Gand et Pedro Berruguete,” Revue du Louvre 41 [1991]: 82-114). The study of Justus poses notable challenges, owing to the paucity of documents, attributional uncertainties, and the generally poor condition of the works themselves. Francesca Bottacin bravely tackles these problems head on.

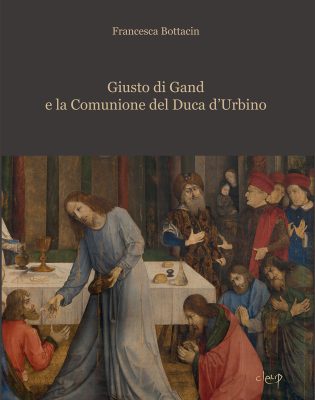

The Communion of the Apostles, the altarpiece for the Confraternity of Corpus Domini at Urbino, is Justus’s only documented work and the starting point for any study, despite its irredeemably compromised condition. Chapter 1 provides a clear and concise account of the documents and attribution. It also proposes a new identification for the exotically dressed, bearded man beside Federico da Montefeltro as Cardinal Bessarion, a friend of the Duke and author of a treatise on holy communion, who confirmed Federico’s infant son Guidobaldo at Gubbio, in April 1472. This is arguably a more plausible identification than the traditional one (derived from the seventeenth-century Urbinate historian Bernardino Baldi) of this figure as the Shah of Persia’s envoy, not least because it explains the otherwise puzzling presence of the infant Guidobaldo in the painting. With its sacramental connotations, this reading also underscores the altarpiece’s central theme of Christian initiation. Nonetheless, it is odd that a generic type (derived from Dirk Bouts’s Martyrdom of St. Erasmus) should have been used to represent the Cardinal, whose likeness was well known in Urbino and indeed features among the Famous Men in the studiolo.

The problem that besets any attempt to study Justus of Ghent is that of his identity and the attribution of the handful of works associated with him – questions that are unpicked in the next two chapters. “Giusto di Guanto” is named in the payments for the Communion by the Confraternity of Corpus Domini between 1473-74, and by Vasari as the painting’s author, in 1550. He is presumably identical with the unnamed master from Flanders mentioned by Vespasiano da Bisticci in 1482 as having painted the Famous Men in the ducal studiolo. Giusto/Justus is convincingly identified as the Ghent painter Joos van Wassenhove, who is known to have left Ghent for Italy some time before 1475. This artist is usually thought to have painted the Calvary triptych in Saint Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent, and the Adoration of the Magi, now in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, before departing for Italy. Bottacin assigns these to a follower of Bouts, arguing that conceptually and in execution there are gulfs between them and the Urbinate works, explaining their kinship with the Communion to a shared Boutsian heritage. These arguments are persuasive; the forthcoming publication of the restoration of the Calvary should shed further light.

The attribution of the other Urbinate works – the Famous Men, the Double Portrait of Federico and Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, the Liberal Arts, and Federico and Guidobaldo Listening to a Lecture – has been contentious since the 1920s, when it was first suggested that they were the work not of Justus, but of the Castilian painter Pedro Berruguete. This assertion has remained remarkably persistent, notwithstanding Mauro Lucco’s cogent rebuttal of it on stylistic and technical grounds (“Pedro Berruguete: una questione storiografica,” in Dalla conservazione alla storia dell’ arte…, ed. Gianluca Poldi et al. [Pisa: Edizioni della Normale 2006], 413-79); his view is shared by Bottacin (and this reviewer). Berruguete is not to be confused with the enigmatic painter Pietro Spagnuolo, documented at Urbino in 1477, who resided in the court and was presumably highly regarded. Possibly a Spaniard trained in the Netherlandish tradition, or perhaps an Italian with the surname Spagnolo, he may have worked alongside Justus and been the artist who completed the Famous Men, and perhaps also the Communion.

These complicated issues are succinctly and objectively explained by Bottacin. Scientific research, revealing notably the typically Netherlandish underdrawing, confirms that the Communion is by the same artist who began the Famous Men, i.e. Justus of Ghent. The extent of his involvement in the other works is less clear. Bottacin posits an équipe of artists working together on ducal projects (as at the Ferrarese court), which in her view included an Italian, possibly Bramante, responsible for the increasingly ambitious perspectives found in works such as the Liberal Arts and Lecture. Hedging her bets, she ascribes these works to the “Officina Urbinate-Pietro Spagnuolo (?).” With the caveat that it should also include Justus of Ghent, this is perhaps the most accurate (if cumbersome) designation we can hope to have for the authorship of these works, which may well have been executed by a team of artists with different backgrounds and strengths.

Chapter 4 investigates other aspects of Justus’s activity in Urbino. It tentatively attributes to him the Salvator Mundi on canvas in the Cà d’Oro, possibly a banner for the Corpus Domini; discusses his possible role in providing designs for the Netherlandish tapestry weavers and embroiderers employed at the court (convincingly, a cope in the Museo Diocesano, Gubbio, and, less demonstrably, the Annunciation tapestry at Urbino); and examines his relationship with Giovanni Santi. Particularly interesting here is Santi’s use of the Netherlandish technique of powdered glass as a siccative, also found in the Communion.

The final part of the book comprises separately authored studies on aspects of the Communion. Livia Depuydt-Elbaum notes past and present collaborations between the KIK-IRPA and the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche. Andrea Bernardini, drawing extensively on unpublished sources, presents an important account of the painting’s musealization, from the seventeenth century, when it was still on the high altar of the Corpus Domini, to its most recent display (2014) in the Galleria Nazionale, including restorations and exhibition history. It includes a fascinating episode in 1904 when the city authorities sought to sell it, along with Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation; the Berlin, Dresden and Brussels museums were approached, as was the Uffizi, whose director envisioned displaying it opposite the “much less precious” [di pregio assai minore] Portinari triptych!

Recent photography and pigment analysis carried out for this publication shed significant new light on the Communion’s execution and state of preservation. Gianluca Poldi discusses the paint surface, the underdrawing and, with Maria Letizia Amadori, the materials and technique; there is also a short section on Uccello’s predella panels (imaged concurrently). In detail, their findings will furnish valuable food for further thought; here, the following broad observations must suffice. Firstly, confirming the view of earlier scholars, the state of the paint surface, in some places so thin as to be almost transparent, is almost entirely attributable to earlier, inexpert restorations. Secondly, contrary to some earlier views, the underdrawing and paint surface seem to be the work of a single, very able artist, possibly working at speed. Thirdly, its original quality, and technical sophistication, is clear from the skillful drawing; the range of pigments used; the refined chromatic choices, such as the use of red lake under ultramarine in different combinations to create a range of blue-violet draperies; and the use of powdered glass, notably in the lakes.

What is so good about this book – in addition to these scientific revelations – is that it sets out the status quaestionis and enables the debate to be reopened. Bottacin presents and weighs the evidence clearly and fairly, proposing sensible answers to problematic questions, saying when her conclusions are speculative, or where they go against the scholarly grain, and is frank about acknowledging that due to lack of evidence, some questions simply cannot be answered. She is frank, too, about the remit of the book, which, given the attributional challenges, does not purport to be a monograph in the conventional sense. As she explains, in-depth analyses of the paintings exist elsewhere, in studies clearly signposted in the text. The book is, after all, centered on the Communion, and it is therefore perhaps churlish to lament the limited discussion of some works, notably the Lecture, which merits only a paragraph. To compensate, it contains very useful appendices: a list of works lost, or formerly attributed to Justus; transcriptions of all the documents (from Ghent as well as Urbino); early conservation and restoration records for the Communion. The illustrations are generous, including photographs from the recent technical investigation. There is an English abstract of Bottacin’s text, though not of the supporting studies. In the current state of scholarship, the book is invaluable; what we are still waiting for is a monograph exploring all the works attributed to Justus, not only from a historiographical, attributional, and technical viewpoint, but also from that of imagery, style, exchange, and artistic innovation, both within the local and international context.

Paula Nuttall

Victoria and Albert Museum, London