Wayne Franits’s second monograph on Godefridus Schalcken (1643-1706) reads as an ardent love letter to the late seventeenth-century Dutch artist. A meticulous analysis of a selection of paintings from Schalcken’s oeuvre allows readers to appreciate his technical skills, stylistic adaptability, and innovative contribution to a range of pictorial genres. Franits presents Schalcken as a skillful and ambitious artist who benefitted from the limited competition on the art market in the late seventeenth-century Dutch Republic.

Over the last decades, Schalcken has been the subject of renewed scholarly attention, most importantly in the context of the exhibition organized by Anja K. Sevcik in the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne and the Dordrechts Museum in 2015-16 and the associated symposium (papers from which appeared in the Wallraf-Richartz Jahrbuch, 77, 2016). Recent dissertations by Nicole Cook (University of Delaware, 2016), focusing on eroticism in Schalcken´s paintings, and Sander Karst (Utrecht University, 2021), examining the activity of Dutch artists – including Schalcken – in late seventeenth-century London, are referenced extensively. Franits builds on the many new insights provided by this recent scholarship. By actively engaging with the research of his fellow Schalcken experts in the main text and especially in the comprehensive endnotes, he offers the reader a chance to partake in a lively scholarly conversation.

Franits asserts in the introduction that a “revision of Schalcken’s stylistic evolution as an artist was in order” (8) due to the emergence of new paintings on the art market since the publication of Thierry Behermann’s French-language catalogue raisonné in 1988. The author meets this objective by discussing a selection of representative or otherwise significant artworks rather than by assembling a revised catalogue of Schalcken’s large oeuvre – currently estimated by at approximately 300 paintings. Besides offering an updated image of Schalcken’s stylistic range and adaptability, Franits demonstrates his profound understanding of the artist’s career and oeuvre, as well as an impressive knowledge of Dutch seventeenth-century art and culture generally, in fascinating if occasionally somewhat digressive excursions. The broad range of subjects treated in his intellectual departures includes art theory, iconography, fashion, biography, theater, hunting and urban history.

In five chronologically ordered chapters, the book provides an overview of Schalcken’s life and paintings, the first of its kind in the English language. The first chapter focuses on the early years and apprenticeships with Samuel van Hoogstraten in Dordrecht and with Gerard Dou in Leiden. Franits makes the interesting case that the instruction that these masters offered their pupil was not limited to artistic examples of styles, techniques, and motifs – all of which the young Schalcken would soon start to emulate. They also modeled certain socio-economic practices (gentlemanly attitudes and other strategic behaviors) that, the author shows, served Schalcken well throughout his career.

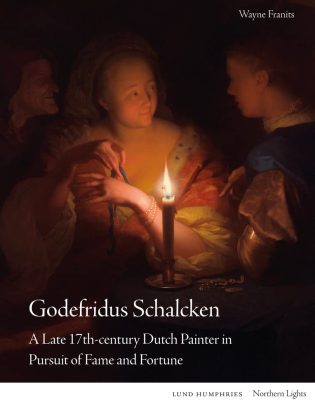

The second chapter, on Schalcken’s career as an independent master during the 1670s, makes clear that, although the painter’s success as a portraitist was undoubtedly the result of his great aptitude in conveying the likenesses of wealthy Dutch burghers, he also benefitted from the absence of serious competition. The narrative that the talented Schalcken often found himself in the right place at the right time – and knew exactly how to profit from this good fortune – soon becomes a familiar aspect of the painter’s career. It was during the 1670s that Schalcken’s reputation as a painter of sensuous candle-lit scenes became firmly established. As the author states:

“Schalcken would soon surpass his master [Dou] in the rendition of artificial illumination both in the complexity of effects and the much wider range of subjects (and even genres) to which he applied it. By the end of his career, nearly 30 per cent of his prodigious output would be dedicated to nocturnal imagery.” (49)

This section of the book also stresses the variety of Schalcken’s output and his excellence and innovative contributions in genre and history painting, portraiture and still life.

The third chapter examines Schalcken’s confident and deliberate steps on the international stage before his departure for London in 1692. The author draws the readers’ attention to another assortment of stunning paintings that emphasize the master’s skill and creativity, as well as his growing maturity. As elsewhere in the book, Franits’s precise, beautifully composed descriptions reinforce the reader’s appreciation of these works. To give a taste of the character of these descriptions, on pages 64-68 the author evokes an “intoxicating little panel” entitled Young Woman before a Mirror (c.1684-6, Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne) from a range of perspectives. He discusses Schalcken’s flowing brushwork and Arnold Houbraken’s praise of it, as well as the painter’s mastery in replicating textures and flesh color – the latter in the light of both early modern art theory and modern technical analysis. Franits points to Schalcken’s particularly innovative and intimate composition, designed, he posits, to obscure the reflection in the mirror from the viewer. Lastly, the author invites the reader to explore the panel’s apparent yet complex eroticism, engaging with Nicole Cook’s insights on the matter. The author approaches other works from this pre-London phase of Schalcken’s development from a similarly wide range of perspectives, also investigating their patronage, iconography, and broader cultural significance.

Chapter Four focuses on the six years Schalcken spent in London. Since this period of the artist’s career was the subject of Franits’s previous monograph Godefridus Schalcken: A Dutch Painter in Late Seventeenth-Century London (AUP, 2018), a condensed reiteration of the wealth of information contained in that publication was seemingly inevitable. The chapter’s place within this chronological overview of Schalcken’s career could have presented an excellent occasion to compare Schalcken’s career in the Dutch Republic with his activity in the distinctly different context of the rapidly developing art center of late seventeenth-century London.

In the fifth chapter, the author discusses the last decade of Schalcken’s life, presenting the culmination of the artist’s career in terms of artistic achievements and patronage. He carefully reconstructs Schalcken’s dealings with Elector Palatine Johann Wilhelm II. Regrettably, the chapter lacks the enthusiasm of Franits’s previous chapters and the editing is less careful (e.g. repetition of the section on the ekphrastic tradition of nocturnal imagery, p. 128 from p. 90). The short and recapitulating Conclusion similarly lacks the passion of the rest of the book – the narrative of talent and good fortune spun out once more – making us wonder whether the author’s love for his artist had waned somewhat in the process of writing the book. It is a little surprising, but certainly in line with the generally admirative tone of this publication, that Franits chose not to elaborate upon the negative judgements about Schalken by eighteenth-century biographers like Jacob Campo Weyerman and Horace Walpole; he did discuss this (s)fortuna critica at length in the 2018 monograph.

If the reader is not yet an admirer of Schalcken, it is quite probable they will become fascinated or even a little enamored with him thanks to Franits’s beautifully illustrated and well-written study.

Marije Osnabrugge

Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam