Ada de Wit’s new book performs many services. Most narrowly, it is an insightful monographic treatment of the greatest decorative sculptor of the second half of the seventeenth century in both England and the Netherlands. Most art historians, however, will be more interested in its many other aspects: its consideration of Anglo-Dutch artistic relations; its foray into European court culture; its coverage of shipbuilding and maritime artistry; its presentation of Dutch Calvinist attitudes toward ornament; its discussion of the social strivings of artists both in Holland and England; its consideration of the culture of the Dutch and English country house, and its investigation of art patronage in the Netherlands during this period.

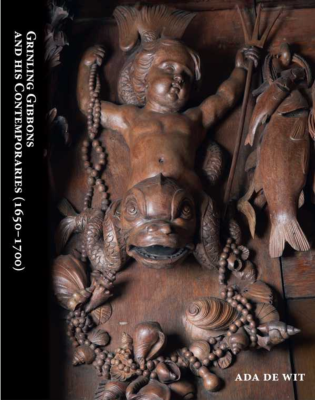

Gibbons and many of his contemporaries worked principally in limewood rather than oak, the traditional wood in northern Europe. Limewood is a malleable material that permitted the pyrotechnics of drapery folds developed by Germany’s early modern carvers such as Tilman Riemenschneider and Veit Stoss, as Michael Baxandall has discussed (The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980). In seventeenth-century England and the United Provinces, it enabled virtuoso treatment of often interlacing and openwork ornamental motifs. Gibbons and his colleagues tended to let the blond tonality of limewood contrast with the darker oak of the background wall panelling. Or they had it painted white to resemble marble and agree with the classicizing idiom of the time.

De Wit’s book treats traditional sculpture only peripherally. Its subject is not the tombs and portrait busts that characterized the elite sculptor’s career in Holland and England. It is rather what we might call decorative carving: ornamental frames for paintings, mirrors, and barometers; mantelpieces, overdoors – but also staircases, interior portals, chancel screens, and pulpits. Most interestingly perhaps, it also includes the formidable and often magnificent carving of warships and aristocratic yachts, whose sterns bore a fabulous mixture of figural and ornamental sculpture. It is a thorough and extremely well-researched investigation of an artistic terrain that could be only partly examined in Peter Thornton’s more expansive and ground-breaking study, Seventeenth-Century Interior Decoration in England, France and Holland (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1978).

The Dutch cities of note in this study are Rotterdam, with its great port, and The Hague, center of court life. This book is also a tour of the great palaces and country houses of the United Provinces and England including Het Loo, Noordeinde, Honselaarsdijk, and Middachten on the continent and Ham House, Kensington Palace, and Hampton Court in Britain.

Grinling Gibbons styled himself a sculptor rather than a simply a carver of ornamental designs in wood. Sir Godfrey Kneller’s (lost) portrait of Gibbons portrays him grandly measuring a copy of Proserpina’s head from Bernini’s famous figural group showing The Abduction of Proserpina, today in the Borghese Gallery in Rome. Yet there was contemporary criticism of his handling of stone, and his rather dull Tomb of Archbishop Thomas Lamplugh in York Minster does little to sway such doubters. De Wit describes the rise of the professional association in The Hague, the Confrerie Pictura, to which many painters and sculptors belonged. The Confrerie Pictura stood in opposition to the older Guild of St. Luke, which still conveyed the notion of artisanal craft rather than liberal art. Equally interesting is the relation between these carvers and so-called architects. Jacob Roman, a prestigious architect who worked for the court in The Hague, began his career as a wood carver. The decisive shift came in 1691, when he sold his wood carving tools and henceforth acted solely as an architectural designer.

Gibbons did carve some virtuoso figural reliefs in his career including an impressive scene of the Crucifixion. These limewood historical scenes compare well with the better-studied boxwood and ivory reliefs of the seventeenth century. For the most part, however, Gibbons and his Dutch colleagues eschewed figural forms. Theirs was an art of garlands, drops of fruit, musical instruments, military trophies, acanthus leaves, and the occasional putto. Dutch Calvinists had long expressed an aversion to conspicuous figural carving with its connotations of idolatry, as Frits Scholten has shown. In 1601, at the beginning of the century, the orthodox congregation of Hoorn had forced the sculptor Hendrik de Keyser to remove the figural framing around the epitaph for the physician Theodorus Velius. A particularly devout crowd threatened to destroy the monument if it were placed in the church in its original state (Scholten, Sumptuous Memories, Zwolle: Waanders, 2003, 10). As luxurious as the carving on certain Dutch pulpits was, it seems restrained in comparison with the theatrical Flemish pulpits of the time that include such life-size figural scenes of the Expulsion from Paradise and the Conversion of St. Norbert. English audiences would prove more lenient in this matter than their Dutch contemporaries.

Gibbons was born to English parents in Holland. His father had been a merchant adventurer stationed in Rotterdam, and it was in this city that the artist had his initial training. It is an open question as to whether he then studied under Artus I Quellinus in Amsterdam. Quellinus’s classicizing sculptures for Amsterdam’s town hall certainly established a rough canon of forms that Gibbons would adopt and revise. Gibbons was one of several artists who worked both in the Netherlands and England. Anglo-Dutch artistic and commercial relations has become a popular sub-discipline in early modern studies. Important treatments of this phenomenon include Lisa Jardine’s Going Dutch: How England plundered Holland’s Glory (London: Harper Press, 2008); Mary Bryan H. Curd’s, Flemish and Dutch Artists in Early Modern England: Collaboration and Competition, 1460-1680 (London and New York: Routledge, 2010) and Joanna Mavis Ruddock, “Dutch Artists in England: Examining the Cultural Interchange between England and the Netherlands in ‘Low’ Art in the Seventeenth Century,” Master’s Thesis, University of Plymouth, 2017). England proved fertile ground for foreign artists, especially sculptors and architects from the Netherlands. With the Restauration of the Stuarts in 1660 and the fire of London in 1666, there was much work to be done and a stable government to commission it. Of course, Anthony van Dyck had established a vaunted career on both sides of the channel under Charles I. Anton and Thomas Quellinus, sons of Antwerp’s Artus II Quellinus, worked in both the Low Countries and Britain after the Restauration. Jacob Roman also received commissions in both countries.

Among the most interesting and complex sculptural genres that De Wit surveys are ship carving and carriage decoration. Ship sculpture was a pan-European affair, though both England and the United Provinces, as leading maritime nations, excelled in this field. Gibbons accepted many commissions for important English ships. None of these vessels have survived, though drawings for and after their decoration by Gibbons and others have been preserved. Ships had long been an artistic subject across media for sea-faring nations. Pieter Bruegel famously designed six engravings of warships during the mid-sixteenth century. A hundred years later, Jan van de Capelle and Simon de Vlieger dedicated a large part of their oeuvre to paintings of sea battles, maritime festivities, bays laden with ships of various sorts, and harbors. The Dutch painters Willem van de Velde, father and son, left the Netherlands for England, where they found ready employment in portraying the foremost British sailing vessels of the day. The only well-preserved example of seventeenth-century ship carving that can be seen today is the Vasa, a Swedish warship that sank on its maiden voyage in 1628, a few hundred meters from its port. Its recovery and restoration, beginning in 1961, has been little short of a miracle. It is now displayed in a museum built expressly for it in Stockholm, where it still reveals much of its sculptural decoration.

Carriages were essential accoutrements of aristocratic life. Ornate carriages were commissioned for specific festivals; they were employed in joyous entries and processions associated with weddings, funerals, and religious holidays. Most of these vehicles have disappeared, though there remain a few illustrative examples. The Speaker’s Carriage from around 1698, probably designed for William III by Daniel Marot, is preserved in the National Trust Carriage Museum at Arlington Court, and an equally elaborate number, most probably Maria Anna of Austria’s coach and likely made in The Hague, can be found in the Coach Museum in Lisbon.

Ada de Wit’s book thankfully avoids the pitfalls of nationalist scholarship, partly by covering artistic development across national boundaries. It is study that many cultural historians of the later seventeenth-century will find profitable and inspiring.

Ethan Matt Kavaler

Victoria College in the University of Toronto