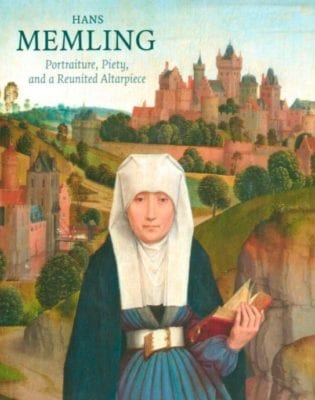

New York is a city fortunate enough to contain a significant group of paintings by Hans Memling. From portraiture (the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Tommaso di Folco Portinari and Maria Portinari are standout examples) to sacred scenes, visitors to Manhattan have the opportunity to experience numerous examples of the artist’s skill. Many of these artworks survive as fragments, requiring their viewers to construct a mental image of the ensemble to which they originally belonged. Physically re-assembling panels from one of Memling’s triptychs for the first time in the United States formed the impetus for The Morgan Library & Museum’s exhibition Hans Memling: Portraiture, Piety, and a Reunited Altarpiece, a show that duly emphasized the city’s rich holdings. Memling’s so-called Crabbe Triptych, named for the commissioner Jan Crabbe, Abbot of Ten Duinen (1457-1488), is now divided between the Museo Civico in Vicenza, which owns the central Crucifixion scene, the Groeningemuseum in Bruges, which possesses the demi-grisaille Annunciation of the exterior, and the Morgan Library & Museum, in whose collection the inner wings are kept. The reconstructed altarpiece was displayed in the Morgan’s Clare Eddy Thaw Gallery alongside other paintings – mostly portraits – by Memling, an epitaph by the Master of the Ursula Legend, as well as manuscript illuminations and drawings.

Comprised of six chapters, and authored by an impressive group of specialists, the accompanying catalogue is an excellent introduction to the main issues surrounding the triptych. The publication is both a valuable guide to the artwork and an introduction to artistic practice in the fifteenth-century Low Countries across media. John Marciari’s opening chapter charts the movement of the triptych’s inner wings from their earliest documented reference in 1855 to their purchase by John Pierpont Morgan from the Kann sale and beyond, to more recent exhibitions. The essay uses other objects in the exhibition to contextualize the Crabbe Triptych within Memling’s creative output, highlighting the artist’s superb portraiture as well as the contemporary relationship between panel paintings and manuscript illumination.

Chapters two and three, written by Till-Holger Borchert and Noël Geirnaert respectively, outline the biographies of the two most significant actors in the triptych’s creation: Hans Memling and Jan Crabbe. Borchert summarizes the known facts about Memling’s origins, training, and career from Germany to Brussels and Bruges, describing notable artworks and emphasizing the influence of Italian patrons on the artist’s corpus. Jan Crabbe’s life is also filled with fascinating events, which Geirnaert sets out in some detail. However, Geirnaert gives little attention to the lives behind the painting’s other portraits, glossing over disturbingly violent events in the remarkable existence of Anna Willemszoon, Crabbe’s mother. Memling’s sensitive rendering of Anna’s face is particularly impactful and engaging; indeed, it is the face of a woman about whom one wants to know more. Anna’s influence on Jan and his triptych are only hinted at in Geirnaert’s acknowledgment that the commission took place close to the 1489 gift of land from mother to son. Crabbe’s international connections nicely mirror those of Memling, with both Geirnaert and Borchert’s essays stressing the vast networks that centered on Bruges and its environs.

Technical examination of the Crabbe Triptych forms the basis of Chapters four and five, written by Maryan Ainsworth (Chapter four) and Gianluca Poldi and Giovanni C.F. Villa (Chapter five). Ainsworth employs technical analysis to describe the triptych’s production, which, as the author notes, likely involved workshop assistants. Unlike the following essay, which reads more like a scientific report, Ainsworth effectively situates her observations of technique in terms of their art-historical significance. She attributes the underdrawing of the triptych exterior to Memling himself but agrees with other scholars who believe the paint layers to be by assistants, which suggests a more nuanced relationship between the development of the demi-grisaille and the master painter. X-radiography of the left wing revealed an earlier design featuring an Anna Selbdritt composition that was worked up beyond the underdrawing to subsequent paint layers. Ainsworth connects this to Memling’s German origins, noting the popularity of the Anna Selbdritt iconography in that region, and further links the now-hidden design to a painting at the Rijksmuseum Twenthe, Enschede.

Poldi and Villa focus their study on the underdrawing of the Vicenza panel and list several changes, revealed with infrared reflectography (IRR), which took place during its production. Their piece updates a 2003 campaign of technical study and features a bullet-point summary of ‘important changes that occurred during the working process’ (pp. 81-85). These changes, described primarily in terms of their compositional function, leave rather a missed opportunity to analyze their potential impact on our comprehension of the triptych’s debated history of construction in the years around 1470. The authors highlight the detection through IRR of two underdrawing media (liquid and dry) below the paint surface. Small amounts of silver were also detected in some areas using x-ray fluorescence (XRF), a discovery that suggests a possible third underdrawing medium. This finding is left tantalizingly underdeveloped in terms of its implication for our understanding of Memling’s creative process within his workshop.

Ilona van Tuinen’s overview of drawings in the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Low Countries highlights their function, major developments within the medium, and the challenges facing their study. Although we have no extant drawings by Memling, Van Tuinen’s essay offers readers a sense of how artists from Memling’s time engaged with the medium, using examples taken primarily from the Morgan’s collection. In pointing out the rarity of surviving fifteenth-century drawings, Van Tuinen’s chapter complements the preceding chapters that discuss Memling’s underdrawing. The slight emphasis on portraiture drawings – mainly examples produced after Memling’s lifetime – is appropriate for an exhibition that explores the importance of creating and owning a likeness.

The catalogue is successful in celebrating Memling’s early achievements in Bruges, setting these accomplishments in the context of artistic production in fifteenth-century Flanders. However, it leaves several questions unanswered and sets the stage for further research into the triptych rather than offering new insights into its construction. The publication’s succinctness may come at the expense of more penetrating analysis, particularly concerning the artwork’s complicated dating. In scope, the exhibition and publication match, focusing on artworks from local New York collections that help contextualize Memling’s triptych and portraiture production. A larger exhibition, involving major international loans of other Memling paintings as well as works by Rogier van der Weyden, would be required to address the more complicated questions raised by the Crabbe Triptych as set out by the Morgan essays. The catalogue provides an updated overview of these central questions and encourages a cross-media approach to future study.

Nenagh Hathaway

Yale University