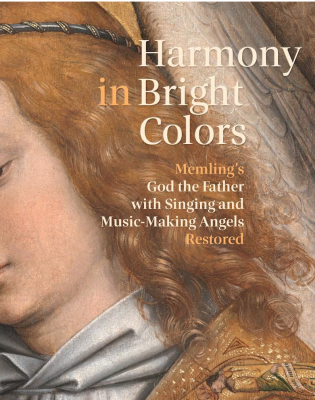

Based on the 2017 symposium organized to celebrate the culmination of the sixteen-year conservation of Hans Memling’s God the Father with Singing and Music-Making Angels (Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp), Harmony in Bright Colors presents a fascinating, interdisciplinary approach to this monumental artwork. The surviving panels are among the largest examples of fifteenth-century Netherlandish painting, although they represent only a small part of the original polyptych, which was created for the Benedictine monastery of Santa María la Real in Nájera, Spain. This luxuriously produced book successfully contextualizes Memling’s paintings from their creation and original installation to their contemporary gallery presentation in Antwerp.

The essays, which range from detailed reports of the technical analyses that accompanied the conservation project to a musicological survey of the instruments depicted, interpret Memling’s panel paintings in nuanced, sophisticated ways. Although each of the contributors approaches the topic as specialist of their subdiscipline, the authors and editors have successfully produced a text that is completely accessible to a wide range of scholars no matter their disciplinary expertise, including advanced undergraduate and graduate students. This is achieved through clearly articulated explanations of complex research methodologies and copious high-quality images and diagrams illustrating each point. For example, the inclusion of a key diagram (pp. 8-9) that designates numbers to identify individual angels and the locations of all the details, macro photos, and micrographs featured in the subsequent essays enables the reader to follow which specific areas are being analyzed and how these visual passages relate to the overall composition. Similarly, the inclusion of arrows and explanatory text alongside many of these details, sample cross-sections, and infrared reflectographs assists those less experienced in “reading” these types of visual evidence. The result is a publication that not only provides important insights into Memling’s painting process, the provenance of the panels, and significance of the commission, but also models the benefits of a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach.

The editors organized the essays thematically, enabling connections and comparisons between the different areas of research. The first essay, “The Conservation and Restoration of Memling’s God the Father with Singing and Music-Making Angels” by Lizet Klaassen and Marie Postec, serves as an introduction to the paintings by providing a broad overview of their conservation and a brief description of the panels’ condition prior to the most recent interventions. This is followed by two essays analyzing the history of the paintings. In “Hans Memling’s Altarpiece for the Benedictine Abbey Church of Nájera,” Bart Fransen and Louise Longneaux use meticulous archival research and visual comparisons to trace the original commission and propose a hypothetical reconstruction of the entire altarpiece, most of which is no longer extant. This endeavor is aided by the discovery of a new document – an eighteenth-century copy of the now-lost Libro Segundo de Censos – which describes the economic activities of the Benedictine abbey in Nájera during the fifteenth century and contains three references to Memling’s commission. The inclusion of reproductions of every folio of this document in an appendix enables further engagement with the text and will be incredibly helpful for future research. Ingrid Goddeeris’s contribution, “From Nájera to Antwerp: How Memling’s God the Father with Singing and Music-Making Angels Ended Up in Belgium,” provides a similarly nuanced history of the complicated negotiations and transactions pertaining to the panels’ provenance. Goddeeris discovered that many different dealers, art historical experts, and even modern artists were involved in various ways in the sale and purchase of the surviving paintings.

The next five essays explore the impact of technical analysis on our understanding of Memling’s materials and processes. Three of these essays address the recent conservation interventions. “Materials and Painting Technique of Memling’s Nájera Panels” by Klaassen, Postec, Geert van der Snickt, and Marika Spring provides a detailed report on the conservation process and technical examination of the paintings. The research team also explicitly looked for evidence of the impact of the large scale of the project on Memling’s production, specifically the involvement of his workshop. The discovery of small variations between the preparation of the panels and the painting technique hint at ways in which assistants may have contributed to the creation of these stunning works. One of the major difficulties encountered during the restoration was the presence of an oxalate crust between the varnish layers and the paint layers in large portions of the composition. Catherine Higgitt’s essay, “Memling’s God the Father with Singing and Music-Making Angels: Oxalate Formation in Old Master Paintings,” discusses the composition of the crust and some of its possible causes. These two contributions discussing the paintings’ treatment are complemented by Postec and Klaasen’s essay, “The Frames and Framing of Memling’s Nájera Panels.” Analysis of the frames revealed that some of the wood is likely from the original altarpiece, and although the wood has been extensively reworked and augmented by modern additions, the pieces of the surviving frames hint at the original installation.

The conservation team’s research question regarding the potential involvement of Memling’s workshop in the production of the altarpiece is further supported by two additional contributions. Maryan Ainsworth, in “Memling’s Preliminary Working Stages: The Nájera Panels in Context,” contextualizes the underdrawings revealed by infrared reflectography within Memling’s oeuvre. By carefully analyzing both the media used and the draftsmanship, Ainsworth argues for Memling as the sole creator of the underdrawing even as the discovery of color notations suggests the involvement of assistants and journeymen during the execution of the paint layers. “Memling’s Workshop” by Till-Holger Borchert similarly attempts to identify the impact of collaboration through careful comparison between the Antwerp panels and other works attributed to Memling. Borchert asserts that even though differences exist in the painted surfaces of Memling’s pictures, these may be due to scale, differences in budget, or disparities in the time designated for completion. Therefore, some of these variations may not specifically be attributed to different hands in the workshop while the interpretation of other differences may be counterintuitive. For example, Borchert states (p. 189) that a more tightly finished underdrawing may indicate a passage that was intended to be completed by the workshop, which may have needed additional assistance.

The final four essays provide avenues for interpreting the paintings’ imagery. In “Vestments and Textiles in Memling’s Nájera Panels in Context,” Lisa Monnas identifies the different luxurious textiles worn by the figures, specifically the angelic concert. By comparing the imagery to both surviving textiles and depicted textiles within Memling’s other paintings, Monnas argues that his representation of these fabrics contributed to the luxurious “realism” of the heavenly scene. The musical instruments depicted similarly reflected contemporary concepts of music and its place in daily life. Karel Moens, in “Music and Musical Instruments in Memling’s God the Father with Singing and Music-Making Angels,” carefully identifies each of the instruments in the panels and argues that Memling’s organization of singing and music-making angels reflected the different kinds of music encountered in the fifteenth century. Keith Polk furthers this analysis by arguing that the division of instruments across the picture plane aligned with the different kinds of music created in Bruges, specifically the various types of performances of the Bruges civic ensemble. The final essay in the volume, “The Musical Experience of the Nájera Panels, Paradisi porte: Memling’s Angelic Concert” by Wim Becu, discusses the Artists in Residency project of the Oltremontano Antwerpen ensemble, in which Memling’s depictions of musical instruments were combined with musicological research in order to design and build three-dimensional replicas. Compositions were developed based on the musical traditions of fifteenth-century Bruges, specifically the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin and the activities of the civic ensemble. The researchers also considered how the playing techniques demonstrated by the angels may reflect contemporary music making practices. The resulting compositions (included via CD and also available on YouTube) bring Memling’s painting to life and highlight the performative qualities of altarpieces, exemplified by the Antwerp panels.

Taken in total, Harmony in Bright Colors: Memling’s God the Father with Singing and Music-Making Angels Restored is an important contribution to the study of Netherlandish painting and will be an essential source for future scholarship on this topic.

Jessica Weiss

Metropolitan State University of Denver