Household Servants and Slaves: A Visual History, 1300–1700 follows a line of enquiry on the under-represented in European society and art that the author Diane Wolfthal, professor emerita of art history at Rice University, has cogently pursued for years. Indeed, this study may beneficially be read in conjunction with another recent book edited by Wolfthal, along with Isabelle Cochelin, “We are All Servants”: The Diversity of Service in Premodern Europe (1000-1700) (Toronto: Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies, 2022). They complement each other in that the various societal understandings of “service,” including to God and to one’s temporal lord in Europe, provide valuable context when exploring the issues of invisibility of household servants and slaves that constitute the main theme running through the present book.

Wolfthal frames her investigations in the context of a gradual shift in the range of relationships between master and household servant in Europe over the period 1300–1700, essentially evolving from the more personal to the increasingly transactional and impersonal. Although the publisher’s blurb asserts that the book “covers” four continents, the author makes no such claim, though she does gesture to the growing global reach of European experience and impact with a handful of illustrated texts, primarily European costume and travel accounts, such as on the Congo and Japan, that include servants and slaves. Throughout the book, including the title, she keeps the term “slave” rather than “enslaved” to underline its disturbing essentialist power, so this review will as well.

Chapter 1, “Illuminating the Late Medieval Servant,” begins the author’s account with the image of the household servant as represented chiefly in Northern European, often Netherlandish and Franco-Flemish illuminated books for the wealthy, in the thirteenth to early sixteenth centuries. Wolfthal walks the reader through the ways that servants’ different stations in society and in the household are indicated (as by their drab colors and location in the background) and thus, in her view, “denigrated.” Could the tendency to foreground peasants’ labors, as in the “labors of the months,” be due to their practice of the Mechanical Arts as reckoned by the Church (think Andrea Pisano’s reliefs on the Campanile of the Florence Duomo), especially animal husbandry and agriculture, skills producing a vital product celebrated alongside the Liberal Arts, whereas basic household tasks did not? The power of the Christmas story might play a role too, since the initial announcement of Christ’s birth was to shepherds keeping watch in the fields. For the foregrounding of household servants, one might introduce Renaissance Italian marriage chests featuring depictions of servants moving a bride’s belongings to her new home.

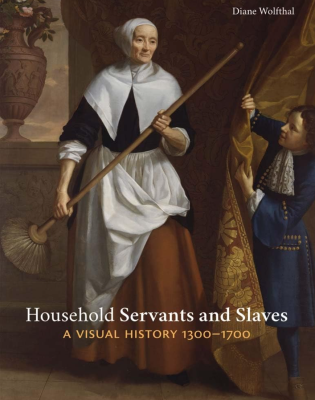

The second chapter, “Servants without Masters,” addresses the portrayal of servants by themselves. Drawings take a leading role, and the chalk studies of ca. 1680 of the family’s household servants by the young Charles Beale, son of the English painter Mary Beale, were a revelation. However, as the exercises of a student, they were carried no further. Paintings include the portraits of Diego Bemba and Pedro Sunda, commissioned to accompany that of their master Miguel de Castro, Congolese ambassador to the Dutch Republic, while Diego Velázquez’s portrait of his slave Juan de Pareja is justly celebrated. But it is the lesser known, full-length (life-size) portrait of Bridget Holmes, dated 1686 (Royal Collection, Windsor), by John Riley, the English royal painter under James II, that is on the book’s cover. The painting has proved puzzling. A senior housekeeper, Holmes was respected and well paid. Dressed for work with her sleeves rolled up, she stands tall on a palatial balcony. With an expression that I read as a half-smile, she wields a long-handled whisk broom (for cleaning up high) in mock threat to the page boy who peeks around a curtain at her. Can we assume that the painting’s scale makes clear that it was intended for display in one of the “more public rooms of a major palace” (103)? This is an intriguing proposal, but in such a setting would its parodying of traditional portraits of the king and his court have been acceptable? As the comedic had been associated with the less educated in that other visual art, the theater, since the ancient Greeks, I throw out the thought that Bridget Holmes might have been affectionately and amusingly installed in an informal setting. In any case, according to the website of the Royal Collection, from 1710 the painting hung in the “Prince’s Eating Room” at Windsor Castle.

Chapter 3, “The Personal Servant,” retraces the varying nature of the servant-employer relationship. The pages on painters as servants and also as masters/employers offer an especially interesting perspective; for this reviewer it was new in the case of the Dutch flower painter Maria van Oosterwijk, who taught her household servant Geertje Pieters, apparently a distant relative, to paint. The situation is less dramatic than Velázquez’s tutelage of his slave, but the illustrated signed work by Pieters is outstanding.

The following chapter, “Paper Servants,” looks at how Europeans represented servants and slaves in illustrated texts, particularly costume books, so popular beginning in the 1500s. I see this as a new interest in drawing attention to (versus ignoring) the range and gradation of roles needed in a complex society, just as global travel prompted interest in different sartorial codes abroad, as in the distinctions among different classes in the Congo. Criticizing Cesare Vecellio, author of De gli habiti antichi e moderni (1590), for failing to “visualize the back-breaking work that servants did” (159) is puzzling as the illustrations are all of costumes or outfits (habiti). On the other hand, the value of local visualization of actions is clear in Wolfthal’s inclusion of Don Guaman Poma, an Inca aristocrat appalled by Spanish colonial abuse of servants and slaves (but who had no objections to enslavement).

Chapter 5 on “The Material Servant” addresses three-dimensional imagery of household servants and slaves as well as their tools, chiefly in the Dutch Republic and England in the 1600s. While the visualizations of material objects in servants’ lives are normally limited to details in two-dimensional imagery of daily life, an exception is the doll house, like that belonging to Petronella de la Court, ca. 1670-90 (Centraal Museum, Utrecht). The second manifestation is the dummy board, slightly smaller than life cutout paintings of figures – servants as well as other household adults and children – that one might be amused to encounter in Dutch and subsequently English homes of the 1600s. The third is the “Blackamoor,” a type of ornamental disposition of the Black body, implying a slave and sometimes manacled, as table or other types of wooden furniture supports. It is hard to know what to say about the insensitivity of spirit their display reflected.

Wolfthal concludes with a bold statement: “Invisibility allowed premodern people to pretend that servants did not perform back-breaking labor that facilitated the lives of their masters and mistresses” (223). Household work could indeed be hard, often with few rewards, but was there any pretense about this? Many forms of labor in pre-modern Europe were extremely taxing and each class had its expectations, although this did not exclude regard, as the author has shown.

Wolfthal raises questions to which many readers will have their own answers, but in the process, they will have profitably followed her lead in probing the visualization of social relationships and the implicit or explicit hierarchies that this inevitably involved/involves.

Joaneath Spicer

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore