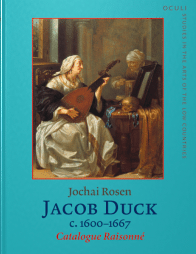

The seventeenth-century Utrecht genre painter Jacob Cornelisz Duck (c 1600-1667) is best known for his depictions of soldiers and prostitutes, but his oeuvre also includes scenes of tranquil domesticity, portraits, saints, and fanciful etchings. Duck’s family was Roman Catholic in a city where about a third of the population professed this faith. His faith appears to have played no overt role in his choice of imagery. At eleven, in 1611, he began his art training when he enrolled in the Utrecht goldsmith’s guild, a guild that encompassed diverse crafts due to its origin in the later middle ages. After receiving his mastership, he studied with Joost Cornelisz Droochsloot (1618-1665) who reportedly gave him drawing lessons. Although Droochsloot’s imagery mainly depicts farmers in rural settings, it is likely that Duck acquired figural skills, and his drawings may well have been from live models. This would account for Duck’s portrait-like types in some pictures and skillfully foreshortened figures in others.

Duck also became masterful in linear perspective, as depictions of manorial barns, inn stables, and monumental church interiors attest. Might Hans Vredeman de Vries’s perspective handbook have taught Duck how to organize interiors with mathematical exactitude? (Vermeer used this publication as an assist, too.) Accompanying the mathematical perspective system is aerial perspective modulating spatial transitions with spectacular tonal mastery. Light diffuses within penumbral interiors to enhance effects of distance and quietude. In such interiors, staffage is small in relationship to architecture, and no narrative unifies the figures’ diverse actions. Spotlighting particular groups guides the eye through space, intensifies hues, and brings about both movement and focus. Light fashions texture as well, be it metallic armor, gold goblets, or shimmering silks. All these qualities are found in Duck’s guardroom scenes and appear too, in his representations of brothels. However, the spatial construct for brothels is not grand; hence, the effects described above, in guardrooms, have less significance.

In keeping with the phenomenal growth of the study of Dutch art that began in the later twentieth century and continues to the present, and after the deluge of studies, books, and exhibitions devoted to Rembrandt, Hals, and Vermeer, Duck and other lesser known masters are now finally receiving their due. The book under review is a classic catalogue raisonné. It is substantially different from the artist’s first monograph by Nanette Salomon (1998). Although her publication has a checklist of Duck’s work, it considers the oeuvre from the perspective of gender, lingusitic theoretical systems, and iconographical traditions. Rosen does not engage Salomon’s ideas; the catalogue only gives page citations.

Rosen’s organization is traditional. It consists of two sections. Subjects are considered in the first; the catalogue constitutes the second. Numbered consecutively, each picture is illustrated, its medium and support identified, followed by dimensions. Panel is the preferred support, but the type of wood used is not identified; copper and canvas are exceptional. Rosen records signature and date, if present. Provenance is given in detail. This is of great interest, in particular, when the picture’s history can be traced to the seventeenth century. In my opinion, establishing the provenance of many hitherto undocumented pictures is the book’s most significant contribution to the study of Duck’s oeuvre. The plates are exceptionally fine and are a boon for future study. Likewise, the extensive bibliography and exhibition citations are essential contributions for further scholarship.

In keeping with the format of such publications, Rosen’s catalogue includes brief paragraphs commenting upon the singular importance of each piece, and addresses authenticity, iconography, and other matters. For example, Duck’s signed A Game of Cards (no. 29), is significant Rosen explains, because it is “one of the few dated paintings by Duck,” and “an early form of the guardroom scene in a stable.” He tells us as well that its appeal to collectors is indicated by the fact that Duck repeated the composition on two other occasions.

Rosen organizes the first section into three categories: guardroom, brothel and prostitutes, and “other.” These groupings are followed by sections entitled “Conclusions” and “Connoisseurship.” Images of Duck’s signatures appear here, with the dates during which he used particular variants. Altogether there are five distinct signature forms that span Duck’s activity from 1627 to 1667. Besides providing a means of authentication, the signatures contribute to establishing chronology. The final form may also indicate a self-conscious self-representation; it has a calligraphic aspect that concurs with the trend Salomon associated with “gentrification” in Duck’s later works. Duck’s career was lengthy, spanning almost four decades, but Rosen authenticates only 157 pictures. Of course, there has been loss, but that he was not more productive is puzzling. Duck’s younger brother was a painter, but Rosen does not identify work by him. Might he have assisted Jacob? Rosen proposes that Duck collaborated with other painters; this speculation is confirmed by the Portrait of Baron Willem van Wittenborst, dated 1644, identified in a family inventory as having been produced by three painters: “Duyck, Poelenburch, and Bartholomeus van der Helst.” Little is known about Duck’s clientele and collectors. However, documents indicate that some pictures fetched high prices and entered elite collections. A Guardroom (no. 6), was acquired by the Archduke Leopold Wilhelm, for example.

One feature of the monograph that I found disappointing is its lack of historical data and contextualization. Since the majority of Duck’s pictures depict the Provinces’ ground forces, it is natural to expect a thorough discussion of the army. This is not the case. Guardroom refers to chambers where a prince maintains guards for protection. But the Dutch term has an altogether different significance in the pictorial arts. Rosen refers the reader to his own publications for further information; however, since this monograph is to be definitive, the information bears repeating. First depicted by Pieter Codde and others in Amsterdam at the conclusion of the Twelve-Year Truce (1621), guardrooms portray soldiers at rest. Who are these men? And why are they in barns, stables and desecrated churches? To denote the soldiers as “mercenaries” is not historically explanatory. Marteen Prak’s volume, cited in Rosen’s bibliography, is a fine source for a comprehensive account of the Dutch military.

Finally, one comment on iconography: what happened to the inimitable Leo Steinberg’s inventions of the “slung leg motif” and “chin chuck?” The contributions of the giants should not be forgotten

Jacob Duck will be of use to dealers and collectors. Art historians can marvel at the illustrations, and use the book for further investigation of the artist.

Susan Koslow

Professor Emerita CUNY, Graduate Center and Brooklyn College