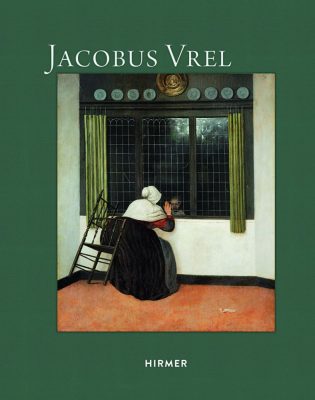

This remarkable monograph was produced to accompany the eponymous international exhibition of Vrel’s paintings that will be on view at the Mauritshuis (Feb. 16 – May 29, 2023) and the Fondation Custodia, Paris (June 17 – Sept. 17, 2023). A work of inspiring scope and erudition, the book treats the reader to a thrilling assembly of research on Vrel, one of Western art history’s most mysterious and elusive figures, in nine substantial articles and catalogue raisonné. The book’s authors and editors were courageous to undertake such a vast and complex project. Their daring has resulted in an ingenious display that sheds new light upon both Vrel and our own historical moment.

Scholarship on Vrel has been forever hampered by lack of fundamental bibliographical information and documented works. (The dearth of solid evidence has led to serious mistakes, such as Théophile Thoré-Bürger’s 1866 misidentification of the artist as Johannes Vermeer.) To overcome this limitation, the editors here widened their book’s scope to examine generations of researchers who studied Vrel. The result is a fascinating narrative wherein the protagonist is left somewhat fluid and the supporting characters, in this case the historians who have worked on Vrel, become as central to the plot as the painter. The focus is as much about the process of art history as a cultural practice as it is about the artist. Because they cannot link Vrel with certainty to a region, a school, or a fixed point in time, the monograph’s editors arranged the catalogue raisonné of paintings spatially. The reader moves through Vrel’s painted environments from public street to private interior in a way that his typically closed-off pictures do not allow on their own.

The book’s first three essays explore Vrel as an historical enigma. In their joint essay, editors Ebert, Tainturier, and Buvelot set a frame around the painter that contrasts with perceptions of Vrel’s works as naive and undirected. Here, and for the length of the monograph, Vrel is evaluated as a precursor to artists like Vermeer and de Hooch, and not an imitator. He is a pioneer rather than a dabbler who followed established artistic trends. This framing raises Vrel as an innovator worthy of our notice and patient consideration. Tainturier’s second essay offers a thought-provoking review of how the artist and his work were regarded by the researchers who explored the paintings in search of their painter and is a reminder that art history is an ever-evolving community practice. Piet Bakker’s essay is a reminder that, when proposing theories about Vrel’s home base, whether it be Zwolle, Steinfurt, or other plausible locations, the historian’s job is almost meteorological: we cannot look directly at the artist, so we must theorize by studying the phenomena moving around him.

The middle third of the monograph hovers close to the surface of Vrel’s paintings, chewing on every cobblestone and window shutter. These essays are some of the monograph’s strongest contributions, displaying at once writerly flourish and a voluminous gathering of detail from meticulous readings of the paintings. Subtle patterns emerge in focused analyses of the roughly 50 works attributed to Vrel. For example, Bernd Ebert directs our attention to the compositional similarities between Vrel’s street scenes and interiors. Both types of images emphasize high verticality and lack plunging spatial depth. The effect gives Vrel’s pictures silent intimacy that feels contemplative, where seemingly insignificant details adopt a curious resonance that stops us in our tracks. Similarly, Dirk van de Vries and Boudewijn Bakker note the extraordinary consistency of the buildings in Vrel’s street scenes. Elements like stone cross-windows and brick gables point to the northeastern Netherlands as the painter’s subject location generally, and Zwolle more specifically. In his essay, Quentin Buvelot peers below the layers of paint to differentiate Vrel’s autograph replicas from their prototypes. Buvelot’s analysis is striking because it reveals that Vrel produced many replicas, normally a practice of painters with more extensive oeuvres. This finding raises more questions that we cannot yet answer about Vrel’s motivations, his primary vocation, and his life.

Other essays explore the material structure of Vrel’s paintings. We learn about how the artist worked and we steal glimpses of his personality by observing his compositional decisions. In his in-depth dendrochronological analysis, Peter Klein offers evidence that the painter was most productive during the 1640s and 1650s. Klein offers an indication about when the artist was active and a possible point of reference for a chronological order of his works by considering the harvesting and preparation cycles of the oak used to produce the panels on which Vrel painted. This analysis yields a significant revelation, that Vrel’s Street Scene with People Conversing in the Alte Pinakothek (cat. 1) probably originated no later than the 1630s. A date this early not only supports Boudewijn Bakker’s judgement that the artist was one of the pioneers of the townscape genre, but also reconfigures Vrel’s relationship to Vermeer.

Another technical essay by Jens Wagner and Heike Stege scans the substance of Vrel’s paintings to reveal the artistic choices made within. The authors evaluate seven street scenes and report that none contains evidence of perspective construction lines. The pentimenti detected in Street Scene with a Woman Seated on a Bench (cat. 4) reveals that the resting woman was once joined by a small girl. The chimney atop a roof in Street Scene with a Bakery by the Town Wall (cat. 11) replaced a nesting stork. A Man Seated by a Window, Reading a Letter (cat. 34) hides another curious choice: Vrel obscures the corners of the room. In fact, he does this in numerous interiors, where the lines that describe the junctions between floor and walls are softened, hidden by objects, or omitted altogether. These choices emphasize the intentionality with which Vrel worked to imbue his images with a peculiar sense of reality, a reading explored further by Karin Leonhard in a wonderfully reflective essay.

Ebert, Tainturier, and Buvelot have assembled a remarkable work of scholarship. Their book’s academic essays push us to consider Vrel with fresh eyes and new questions. Newcomers to Vrel will delight in the sensitive readings of his images, and scholars will find new interpretations to explore. The volume is physically beautiful. The reproductions of the artist’s works are a delight to take in, and isolated painting details reward closer inspection. Vrel is often evaluated in comparison to other painters, but this monograph allows him the opportunity to stand on his own. It shows that Vrel can simply be on his own terms, and the history of art is all the better for it.

Ryan Gurney

San Francisco State University