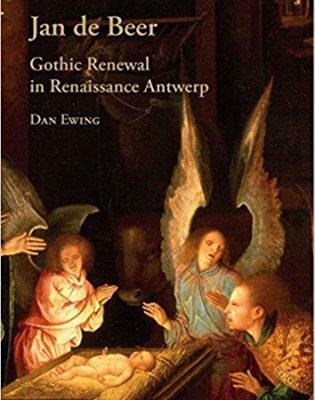

This handsome, well-illustrated book represents a culmination of Dan Ewing’s work on Jan de Beer and will take its place as the standard monograph on this artist for some time to come. For the most part it follows the usual format for a monograph and catalogue raisonné.

Ewing begins with a brief discussion of Jan de Beer’s reputation in the sixteenth century, including praise from Lodovico Guicciardini in his 1567 book on the Low Countries. Subsequently knowledge of the artist was eclipsed until he was rediscovered by Max J. Friedländer in the early twentieth century. This section is followed by a chapter devoted to the artistic and economic situation in Antwerp, the city’s increasing mercantile and financial dynamism and the parallel development of the city’s attraction to artists and, thanks to Ewing, the Pand, where from 1460 on works of art could be purchased on the open market. Especially important here is Ewing’s characterization of the predominant stylistic mode as Gothic, as opposed to Italianate, which manifested itself in architecture, sculpture and painting. As he makes clear, the cultural situation was quite varied and complex and not simply a question of “Gothic” versus “Italianate”. The theatrical exuberance found in de Beer’s work may be called Gothic and is common to the group of contemporary but mainly anonymous artists known as the Antwerp Mannerists, who were the subject of the revelatory exhibition, ExtravagAnt, held in Antwerp and Maastricht in 2005-2006. As several authors have pointed out, the lavish fabrics depicted by Jan de Beer and his contemporaries echo the introduction of a variety of colorful, elegant woolens, silks, and satins into the Antwerp market. On page 38 I was sent scurrying to my unabridged dictionary to learn that “say” was a kind of woolen or silk cloth.

The second chapter is devoted to a thorough discussion of Jan de Beer’s life and career. There one learns about Lieven van Male of Ghent, who in 1516 contracted for a great deal of money to study with de Beer; one also learns that his son Aert de Beer was an artist, but his works, unfortunately, are not extant.

The only fully signed and dated work by Jan de Beer is the Sketch of Nine Male Heads in the British Museum, London. Ewing believes that the drawing was a gift to Joachim Patinir (whose name appears on the verso) and that it should be dated 1520, even though the third digit is illegible. The drawing is a starting point for the study of Jan de Beer, and as with a pattern book, individual heads make their way into de Beer’s paintings. From here Ewing moves into an analysis of Jan de Beer’s drawings, many of which are designs for glass roundels, as well as a consideration of attributions or drawings assigned to the circle of Jan de Beer. As demonstrated in the outstanding exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, in 2010-2011, Jan Gossart was the other identifiable, productive Netherlandish draftsman of the period. It is a curious phenomena that, in contract, we have no accepted drawings for certain artists like Robert Campin, Quentin Massys or Joachim Patinir. There are, of course, large numbers of anonymous drawings.

With twenty-seven pictures ascribed to de Beer, the chapter on paintings is substantial and offers much that is rewarding and insightful. Of special interest is the Adoration of the Magi triptych (Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) that Ewing gives to Jan de Beer and an assistant, whom he convincingly identifies as the Master of Amiens. The theme of the Adoration of the Magi has special significance in Antwerp: the luxurious, exotic gifts bestowed upon the Christ Child became a metaphor for the rare and expensive goods brought to Antwerp by merchants and traders from all over the world. In addition to three versions of the Milan picture, Ewing lists over fifty paintings associated with a lost Adoration of the Magi (cat. no. 10) by Jan de Beer. The seemingly countless renditions of this theme by the Antwerp Mannerists make it hard indeed to think of a sixeteenth-century treatment of the subject that is not to some degree in the Antwerp Mannerist mode. Furthermore, thanks to Ewing, we know that in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries Antwerp merchants often named their sons Gaspar, Balthasar, and Melchior after the Magi.

The book concludes with a compilation of the documents concerning Jan de Beer and a catalogue of the paintings and drawings. Two short but very useful appendices also list Antwerp panels painters who can be associated with extant pictures along with a census of Antwerp sculpture and paintings that is estimated to comprise almost six thousand works, testimony to the extraordinary production of an extraordinary city.

John Oliver Hand

National Gallery of Art