Dan Ewing has written an impressive and essential book about one of the most important but least understood painters of Antwerp. In his famous description of the city, the Italian merchant and historian Ludovico Guicciardini named Jan de Beer one of the four critical artists of the early sixteenth century – along with Quentin Massys, Joos van Cleve, and Joachim Patinir. De Beer, however, was soon forgotten, ignored by Giorgio Vasari, Domenicus Lampsonius, and Karel van Mander. Max J. Friedländer subsequently did Jan de Beer equivocal service. Although the German art historian identified the artist and considered him among the best of his ilk, Friedländer’s denigration of Antwerp Mannerism as a sterile manner opposed to a vital style has haunted de Beer ever since.

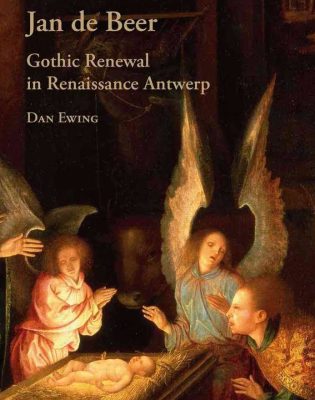

Ewing rescues de Beer from this relative oblivion. He convincingly defines de Beer’s oeuvre of paintings and drawings and narrates their development. Jan de Beer is shown to be the most popular and influential painter of his generation; judging from extant copies, his lost Adoration of the Magi was Antwerp’s best-selling picture. De Beer stands out among the so-called Antwerp Mannerists as an exceptionally expressive if not expressionist painter, one whose tropes of attenuation and excited drapery register the emotional turmoil of witnessing Christ’s Passion. Ewing shows that his most talented epigone, the Master of Amiens, was likely de Beer’s pupil and probably collaborated on the famous triptych by de Beer today in Milan (Pinacoteca di Brera). Significantly, the classicizing painter and theorist Lambert Lombard came from Liège to Antwerp for advanced instruction with de Beer.

Jan de Beer’s engagement with architectural ornament is extensive, and Ewing gives this aspect serious consideration. The painter includes elaborately designed Gothic artifacts in his pictures – from choir screens with intricate tracery to thrones crowned by ogival arches. As Ewing notes, these elements were far from archaic; they represented cutting edge designs comparable to the contemporary architectural inventions of Rombout II Keldermans, the leading builder in the Low Countries. In fact, this very rich Renaissance Gothic was the predominant mode throughout northern Europe during de Beer’s lifetime. It is only our insistence on the timeless relevance of the Renaissance that casts these works as old fashioned.

This is an important observation, for it rescues de Beer from anachronistic reproach and offers a more helpful context for his creations. Ewing wonders whether the exuberant angular folds of drapery – often floating in the air – might be related to the angular, linear aesthetic of Gothic architecture. Ewing makes a gesture toward Michael Baxandall’s period eye in associating linear calligraphy and the rhyming of rederijker verse with the “alliterative” forms in de Beer’s paintings; Baxandall attempted something similar when discussing the German sculptors Veit Stoss and Tilman Riemenschneider in The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany.

These observations prompt us to consider the limits of a Zeitstil. One reason why the existence of Gothic architecture in the sixteenth century is so surprising is that the word “Gothic” is the name given to both an artistic style and an historical period. The same is true of the word “Renaissance.” This doubling became conventional in the later nineteenth century with the aestheticization of history writing. There are obvious problems linked with such a period concept. First, it is often employed tautologically. Since the cultural products of the Gothic or the Renaissance are, by definition, of that style, anything not in this style cannot legitimately belong to the period. Equally problematic is the notion that all artifacts of the age must share some essential formal characteristics—hence, Heinrich Wölfflin’s famous Gothic shoes. Are de Beer’s figures “Gothic”? Or just his ornament?

The Adoration of the Magi by de Beer today in the Musée de la Renaissance Française at Écouen raises other issues. The architectural surround – the dilapidated palace of David – is constructed in a distinctly Renaissance fashion; it is supported by pilasters bearing vertical candelabra components along their sides and by a single, seemingly outsized baluster column. Such ornament was meant to be conspicuous, since it signaled that the artist was au courant with the antique mode that was just being established around 1520, when the Ecouen picture was painted. We might further note that candelabra ornament could stand as a concentrated index of the artist’s faculty of imagination, since the candelabra itself was composed of an endless variety of elements – vessels, floral emanations, and grotesques. The baluster column was, perhaps, the most sophisticated and erudite synecdoche of the antique. Although we tend to think of ancient columns – the Orders – as comprising the well-known Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, and, perhaps, the Tuscan modes, this canon was not definitively established until the 1540s. Before that time the series was in flux; the baluster column and the candelabra column were the most prized. Both are extolled in Diego de Sagredo’s Medidas del romano (Ways of the Romans) of 1526, which was soon translated into French and greatly influenced the leading Netherlandish architectural theorist, Pieter Coecke van Aelst. De Beer’s imposing baluster column stands as a kind of cultural spolia, an appropriation of an elite object and a claim to social and aesthetic relevance.

Ewing’s compelling account prompts further questions about Antwerp Mannerism. The author persuasively argues that this rubric is too narrow a context to capture de Beer’s contribution. And yet the manner – as later art historians have constructed it – dominated much of Antwerp’s production in the early years of the sixteenth century. Can Jan de Beer be seen as an originator of this fashion, or is its genesis and development more complex? How do his works relate to those by other painters who adopt a similar idiom: Adriaen van Overbeek, Jan Mertens van Dornicke, and the Master of the Antwerp Adoration – let alone the young Jan Gossart and Joos van Cleve? These are questions that we can now fruitfully address with the publication of Ewing’s excellent study.

Ethan Matt Kavaler

University of Toronto