Genoa presents something of a wild card in the study of Netherlandish artists. Already in the 1520s, Joos van Cleve’s altarpieces were variously commissioned for there: San Donato, Santa Maria della Pace, and San Luca d’Erbe, in addition to exports for Antonio Cervezo, a Genoese merchant living in the Canary Islands.[1] Such primary works by him as the New York Crucifixion Triptych and the late, Italianate Lamentation Altarpiece (Paris, Louvre) enjoyed receptive audiences in Genoa. Of course, a century later, both Rubens and Van Dyck included productive working periods for the Genoese interlocking patriciate, especially in portraits; and Rubens even published a volume of plans and facades, Palazzi di Genova (Antwerp, 1622).[2]

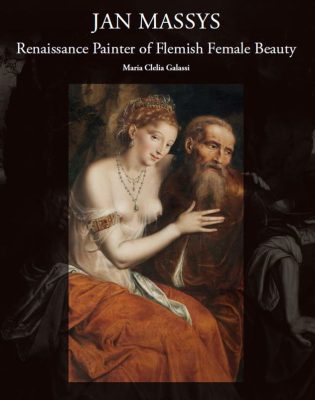

During the sixteenth century, following the generation of Joos van Cleve, yet another Antwerp painter, Jan Massys (ca. 1510-1573), the son of Quinten Massys (d. 1530), also made connections with Genoa.[3] Maria Clelia Galassi, professor at the University of Genoa, has already authored numerous studies about the connections between the prosperous port city and the Low Countries. This book, the product of two decades of her research, focuses on one aspect of Jan Massys’s work, his representation of female beauty.

So what is the Genoa connection? The evidence appears on a late Jan Massys painting, the beautiful Venus of Cythera (signed and dated 1561; Stockholm, Nationalmuseum), centerpiece of the central Chapter Three (pp. 79-105). In that work, as Galassi astutely demonstrates (following Buijnsters-Smets), the background bird’s-eye view shows Genoa’s distinctive topography. A related Jan Massys Flora, Hamburg, 1559, shows the skyline of Antwerp behind a similar villa garden, and the Antwerp association is underscored further by a statue of the eponymous mythic hero Brabo (for the region of Brabant) with city coat of arms before the skyline. Galassi correctly assumes that these pictures’ focus on eroticized females, sometimes contrasted with aged, ugly males, were destined for private clients rather than the open market. Further, she links the emphasis on female beauty, “blonde and cold,” to the influence of a widespread Petrarchan “culture of desire.”[4] Of course, precisely this kind of picture was condemned by Erasmus and by Counter-Reformation theologians, such as Molanus, for its seduction of the male gaze.

Galassi locates the form of this fair-complexioned, “glowing” female type in Jan Massys’s experience of both the School of Fontainebleau and Italy during his decade-long exile from Antwerp (1544-1554) on religious grounds (Chapter Two, 57-64). But his subjects depict many biblical characters with different valences: negative behavior by Lot’s daughters; ambivalent heroism by nude Judith; but also more innocent figures, Bathsheba, Susanna, or a repentant saint, Mary Magdalene.

Patronage of the Venus of Cythera is plausibly ascribed by Galassi to Genoese patrician and international financier Ambrogio di Negro (1519-1601). His personal villa and garden are identified (fig. 3.10) within the picture’s background view of his native city. Galassi also claims that this particular topography stems not from Jan himself, but rather from the hand of city view specialist Antoon van den Wyngaerde, who also made visual surveys for King Philip II of Spain.[5] Thus, Massys need not have visited Genoa himself, but at least he marked his enticing image for a Genoese viewer. The two could have met personally in 1558-59, or else through a Di Negro family representative (p. 104 n.37) in Antwerp, site of a resident factory of the Genoese Nation of financiers.[6] Galassi also makes a case for the importance of an Italian humanist circle in Antwerp, the Accademia di Gioiosi, founded in 1555 and suggests, vaguely, that some other Jan Massys paintings might have emerged from that group. She cites the influential Genoese merchant and amateur in Antwerp, Stafano Ambrogio Schiappalaria, as well as members of the prominent Balbi family (later major patrons of Van Dyck). Gerolamo Balbi (d. 1627) owned Jan Massys pictures – a 1552 Madonna and Child and a Caritas – still remain in Genoa (Palazzo Bianco; figs. 2.27, 2.36).

In a similar vein, Galassi links the Hamburg Flora to imagery in verses by Flemish poet and nobleman Jan van der Noot (1539-ca.1595), an Antwerp alderman but allied with the Reformed Church and forced into exile in 1567 (his verses were published in London). Galassi may too readily see Van der Noot as patron of the Stockholm panel, but surely his sentiments echo the painting, if not the reverse. She offers evidence that Van der Noot returned to Antwerp and converted to Catholicism in 1579, after which he also associated with a Genoese Academy of the Confusi (p. 95).

Arguing against the meretrix associations of the Flora tradition, Galassi opts instead to see a chaste nymph as the subject of the painting. However, both the emphasis on flowers and the offer of a female body to the gaze of the viewer do not preclude those erotic aspects of Flora, goddess of both springtime and fertility.[7] We need only think of Rembrandt’s ambitious early paintings of the same goddess, with flowers (if dressed; St. Petersburg, London), to see the more positive, if enticing aspects of this reclining garden figure. And as a result would the Stockholm painting no longer be a Venus (a 1635 inventory lists her as ‘Goddess Flora’)? Certainly, Galassi reopens the question of erotic females as art subject and how they were received by their owners, but she sees their voyeuristic affect, instead, as “a witty allusive game, a source of visual or perhaps even tactile pleasure, rather than an occasion for real passionate and erotic involvement.” (p. 97) Certainly the Petrarchan model saw the ideal beauty as unattainable and distant, an object of loving contemplation, very like the class-based heritage of medieval courtly love.[8] Indeed, carnal violations by either Lot’s daughters, David’s Bathsheba, or Susanna’s Elders provide negative confirmation for the more artificial representation of female nudity and luxury costume that Galassi discerns in Jan Massys. His body of work holds serious implications for future research into imagery of female nudity from Gossart to the Prague School and Rubens.

Beyond this important aspect of Maria Galassi’s book, many other contributions abound in it. She reveals many new paintings, often still in private collections. As expected in the Me Fecit series of which this volume is a part, attention to painting technique and laboratory examinations figures prominently. Galassi devotes Chapter Four to Massys’s working method of producing both ivory flesh of female beauty and nutbrown male ugliness, Chapters Five and Six to workshop practices and differences in replicas. She begins with Jan’s Quinten Massys heritage for his painter son, tackling difficult distinctions between them and instances as possible collaborators.[9] What this scrupulous discussion ultimately reveals is how such workshop collaboration, even more so with trained family members, should discourage our overprecise or narrow attributions of specific works, despite pressures from museums and galleries.[10] In this opening chapter, along with her considerations of their technique, Galassi also offers a positive reading of money-handlers as a subject in Jan’s early career, possibly for known elite patrons.

Chapter Two is the most biographical, carefully tracing “a career of ups and downs,” including a decade of exile from Antwerp, followed by reinstatement in 1554. Galassi attends closely to social networks of the artist and his family, which she posits as his likely clientele. She posits Jan as the figure painter of New York’s Friedsam Madonna and Child Outdoors, discusses the rediscovered, contrasting Susanna and the Elders (Antwerp, Phoebus Foundation) as “secularized” and erotic, and examines two dated pictures of the holy figures (1552; Palazzo Bianco, private collection; both works once owned by the Balbi) from the exile period. Galassi speculates about where Jan might have spent his exile, positing both northern Italy and Fontainbleau. Finally, she assesses the mid-century Antwerp of Floris, Willem Key, and genre paintings as the visual culture to which Jan returned for his remaining dozen years of work.

Further to the technical aspects, Galassi adds three valuable Appendix topics: fashion (Alessio Palmieri-Marinoni); XRF study of Jan’s Genoese pictures (Michele Brancucci); and digital restoration of original effects affected by deteriorated smalt material in blue areas (Manuela Serando).

All these elements, interpretive (sometimes necessarily speculative) and technical – and sometimes both regarding attributions – contribute to restore the position and the significance of Jan Massys within sixteenth-century Netherlandish painting history.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania

[1]Maria Clelia Galassi and Gianluca Zanelli, “Joos van Cleve und Genua,” in Peter van den Brink, ed., Joos van Cleve. Leonardo des Nordens, exh. cat. (Aachen: Suermondt-Ludwig-Museum, 2011), 64-84, 163, 181-82, nos. 11, 51; John Hand, Joos van Cleve (New Haven, 2004), 2. 56-59, 75, 81.

[2]Piero Roccardo, “Ritratti di Genovesi di Rubens e di Van Dyck: Contesto ed identificazioni,” and Michael Jaffé, “On Some Portraits Painted by Van Dyck in Italy, Mainly in Genoa,” in Susan Barnes and Arthur Wheelock, eds., Van Dyck 250 79-102, 133-150, respectively. Also, Herbert Wilhelm Rott, Palazzi di Genova: Architectural Drawings and Engravings. Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard 22 (London, 2002).

[3]also Villy Scaff, “Ioannes Quintini Massiis pingebat,” in Mélanges d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’art offerts au professeur Jacques Lavalleye (Louvain, 1970), 259-79.

[4]Elizabeth Cropper, “On Beautiful Women, Parmigianino, Petrarchismo, and Vernacular Style,” Art Bulletin 58 (1976), 374-94. On the wider phenomenon in literature, Gordon Braden, Petrarchan Love and the Continental Renaissance (New Haven, 1999).

[5]Richard Kagan, “Philip II and the Art of the Cityscape,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 17 (1986), 115-35.

[6]Colette Beck, “La nation génoise a Anvers dans la premiére moitié du XVI siècle,” in Raffaele Belvederi, ed., Atti del congress internazionale di studie storici: Rapporti Genova-Mediterraneo-Atlantico neel’eta moderna (Genoa, 1983), 445-76; Fernand Braudel, The Wheels of Commerce (London, 1982), esp. 393-94. Galassi notes that Negrone di Negro was banker to Spanish Kings Charles I and Philip II, and Giacomo Di Negro was ambassador of the Genoese Republic to Brussels and Antwerp from 1553 to 1559. The Genoese Nation also sponsored a triumphal arch by young Frans Floris for the 1549 entry of the future Philip II to Antwerp; Edward Wouk, Frans Floris (1519/20-1570). Imagining a Northern Renaissance (Leiden, 2018), 131-55.

[7]Julius Held, “Flora, Goddes and Courtsean,” in De Artibus opuscula XL. Essays in Honor of Erwin Panofsky (New York, 1961), 201-18.

[8]James Schultz, Courtly Love, the Love of Courtliness, and the History of Sexulaity (Chicago, 2006).

[9]Teresa Posada Kubissa, “Cuadros de Quinten Massys y Jan Massys en el Museo del Prado. Actualización de las atribuciones,” Boletino del Museo del Prado 32 (2014), 96-109, an index of the difficulties of separating hands.

[10]Here a confession after a half-century of personal connoisseurship about my 1984 Quinten Massys monograph, based on a 1974 dissertation: earlier efforts to exclude works with even a scintilla of workshop participation marred that book, which would assume a far more inclusive roster today, which would also qualify some bolder Galassi reattributions.