In the course of a new research project on the Crucifixion and Last Judgment in The Metropolitan Museum of Art – star works, attributed to Jan van Eyck – Maryan Ainsworth and her colleagues made the astonishing discovery that the outer, flat sections of both frames originally bore inscriptions in Middle Dutch on all four sides, significant traces of which had survived. This finding gave the project an unexpected and dramatic new focus. The result is the book under review, which constitutes by far the most important study of the paintings since Dagmar Eichberger’s monograph, published in 1987. Ainsworth has contributed new research on their original form and function, the question of attribution, and the relationship of the Crucifixion to the recently rediscovered Eyckian drawing of the same subject in Rotterdam; Sophie Scully and Silvia A. Centeno have investigated technical and scientific aspects; Marc Smith, Christina Meckelnborg, Frank Willaert, and Luc De Grauwe have analyzed the inscriptions. In keeping with Ainsworth’s wealth of experience in the field, discussions of iconography, representational conventions, scientific and technical characteristics, and socio-historical contexts are equally informative and well-balanced.

The Middle Dutch inscriptions have been identified by Smith as translations of the Latin ones on the concave molding immediately proximate to the image, which were executed in pastiglia and gilded. The Dutch texts are in Gothic minuscule; the Latin ones in an archaizing majuscule script. Both sets occupy all four sides of the frames. While the Latin inscriptions in pastiglia are clearly original, the ones in Middle Dutch are not provenly so. Cross-sections taken from the picture plane in the Crucifixion and Last Judgment and from the inscribed concave molding show a layer composed mainly of apatite (bone white) on top of the chalk ground. In those taken from the flat part of the frame, inhabited by the Middle Dutch letters, this layer was not detected. It is possible, however, that the Middle Dutch inscriptions always co-existed with the Latin ones: Smith has dated them to ca. 1450, in keeping with the results of the dendrochronological examination of the frames (the most recent heartwood ring dates from 1402, placing the probable felling date after ca. 1410). Purely in physical terms, it is plausible that the wide, flat outer section of the frame on all four sides was designed to accommodate a second set of inscriptions.

Willaert and De Grauwe demonstrate that some of the verses on the frame come close to the text of a late fourteenth-century translation of the New Testament into Northern Dutch, attributed to Johannes Scutken, a canon regular of the Windesheim congregation outside Zwolle. Of the characteristics of this variant of Middle Dutch, they state:

“[the characteristics] do not point to Van Eyck’s native region, but to an area that is far more northerly: to the northern part of the duchy of Guelders, to Cleves, to Münster or to the Oversticht, i.e. the territory situated between Groningen in the north and Deventer in the south. Our hypothesis is that the vernacular translations of the Bible verses on the frames originated in that region, but that they were subsequently adapted to a southern (Brabant, perhaps Flemish) audience.”

That the paintings were originally a diptych is doubted by Ainsworth, partly because the format would have prevented figures painted in grey on both reverses (described by Passavant in 1841) from being viewed side-by-side but also because the height to width ratio (roughly 2.5:1, including the frames) would be unusually tall and narrow for a diptych. Technical and scientific evidence demonstrates that the two paintings have been assembled at different moments as a diptych and as the wings of a triptych. Ainsworth’s preferred hypothesis is that the Crucifixion and Last Judgment were originally doors to a tabernacle or to a reliquary shrine, which would suit their tall, narrow format and, beginning roughly half-way up the left-hand frame of the Last Judgment, the verse beginning “Ecce tabernaculum dei cum hominibus…” (“Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men”). The additional arguments – that the shrine in question was that of a Miraculous Bleeding Host installed in a chapel in the collegiate church of Saints Michael and Gudula in Brussels, and that the patron was likely Philip the Good, duke of Burgundy – can be traced back to this initial hypothesis. Unfortunately, the lack of surviving Netherlandish examples means that the only significant comparisons are German On the basis of those few illustrated, at least, the imagery does not fit as comfortably as it might within the conventions for this category of object: the images on the doors appear iconic and formulaic, and the figures are relatively large in scale. While the “Ecce tabernaculum…” text adorns the reverse of an example in Senden, Germany, it is inscribed only in the Latin of the liturgy – the appropriate language for the communication of sacred truths. The Crucifixion, by contrast, was at the cutting-edge of innovation in multi-figured pictorial narrative, bringing temporal and geographic specificity to this moment of Christ’s death on the cross, and enabling the viewer to experience the scene as though he or she were present. Minute, affective details draw the viewer in. In this context, the alignment of the Middle Dutch text both with specific segments of the imagery and with the same text in Latin is perhaps best understood as part of an attempt to unite the events depicted (past or future) with present-day acts of “private” lay devotion. This would not exclude Ainsworth’s appealing proposal that the imagery was attuned to the tenets and spirituality of the Carthusian Order, which maintained connections to those living in the world and employed lay brothers. That the patron was resident in Bruges is a possibility not only because of the relationship with Van Eyck but also because the city was a major center of vernacular literary culture.

With respect to the shape of contemporary prayer, it is worth noting that inscriptions present on all four sides of a frame are not always meant to be read in a circular fashion from start to finish. Here, the fact that the two short inscriptions from Revelation 20:13 on opposite sides of the frame of the Last Judgment (“And death …delivered up its dead”; “And the sea gave up its dead”) were enclosed by a border (in the Latin) and painted in black (in the Middle Dutch) suggests that they were important. Perhaps they were the joint starting point of a devotional exercise on the Last Judgment, one that logically began with the theme of bodily resurrection. In that case, it may have been their positioning roughly halfway up each frame that determined the unusual starting position of the “Ecce tabernaculum…” inscription.

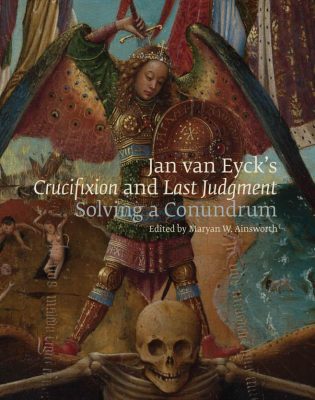

The authors attribute the paintings to Jan van Eyck, suggesting a date of 1436-38. They rightly reject the widely accepted idea that significant areas in the upper half of the Last Judgment were painted by an associate of the Bedford Master: there is no visible sign that the painting is by more than one hand. What the book underlines is how much an attribution to Van Eyck affects the formulation of research questions. In this case, the attribution makes it necessary to argue that physical and technical features of the paintings that would be unique in Van Eyck’s oeuvre – the fact that the frames were integral rather than semi-integral or engaged; the technique of pastiglia for inscriptions; and the unmodified red color of the flat outer frame – are the result of the particularized demands of the commission. It also encourages the idea that the client was Van Eyck’s patron, Philip the Good. If the attribution to Van Eyck is set aside, one is free to insist on the differences and to follow the visual and material clues wherever they lead. It is clear, for example, that the painter’s majuscule alphabet is different from that preferred by Van Eyck, who liked to deploy alternative forms of the same letter, drawing on a mixture of capital, square, and uncial forms (in The Met inscriptions, the letters C and E, for example, occur consistently in the same form). The execution of inscriptions in gilded pastiglia, tightly interwoven with narrative imagery, can be traced back to non-Eyckian traditions of Netherlandish painting: the technique was used for the Latin words “vere filius dei erad [sic] iste,” spoken by a figure to the right of the cross in the Calvary of the Tanners, most often assigned to Bruges or Flanders (ca. 1390-1400?, Cathedral of Saint Savior, Bruges). As Ainsworth demonstrates, the armor of Saint Michael the Archangel in the Last Judgment differs too: it is a Byzantinizing concoction, distinct from the kind of armor that Van Eyck invented for his warrior saints, which incorporates contemporary plate armor. It is unlikely that this shows Van Eyck tailoring the design to this particular commission, however, as the same Byzantinizing combination of plate, textile, and scales is worn by Nimrod in the Tower of Babel (ca. 1500; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), a painting widely and plausibly regarded as a partial copy of a lost work by Hand G. The latter’s oeuvre consistently presents a different set of types from Van Eyck’s.

The debate concerning the attribution will doubtless continue. Whatever the reader’s position, however, the book under review serves its purpose admirably. It is a model of high-quality, interdisciplinary research which presents both a challenge and a genuine inspiration to the reader, forcing the reassessment and rethinking of any number of beliefs and ideas. It will undoubtedly make an enduring contribution to the vast Van Eyck literature on which it so impressively draws.

Susan Frances Jones

Northeastern University London