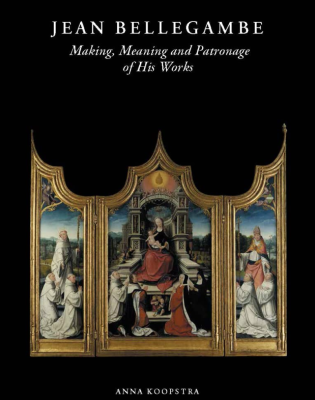

Anna Koopstra’s book, Jean Bellegambe (c. 1470‒1535/36): Making, Meaning and Patronage of His Works, is a helpful intervention, as the first published volume on this Douaisian painter since 1890. The book is not a chronological survey of the artist’s life, nor is it inclusive of his corpus as a whole. Rather, its core chapters focus on five works that Koopstra identifies as key paintings in the artist’s oeuvre. The book’s strengths lie in this organization, with each chapter attending to the themes of the volume’s subtitle as they relate to the painting in question. Other merits include detailed analyses of the archival evidence at the author’s disposal and reconstructions of the artist’s working method assessed through observation and technical approaches. Less convincing are certain assertions about innovation, patronage, and intention, including the parties identified as donors and their potential contributions to the iconographical programs of the works.

No known paintings include Bellegambe’s signature, which has led scholars to rely on attributions and archival documentation to reconstruct his oeuvre. Two works treated at length by Koopstra feature in early archival sources: the Anchin Polyptych of c. 1511‒20 (Musée de la Chartreuse, Douai), which adorned the main altar of the Benedictine monastery of Anchin near Douai, and the 1526 Pottier Triptych (Musée de la Chartreuse, Douai), named after the family whose members commissioned it. After a prefatory biographical chapter, analyses of these two paintings bookend the volume, while another chapter offers some preliminary conclusions about Bellegambe’s materials, painting supports and frames, and working methods. The paintings analyzed in the five case studies are addressed briefly in this chapter, with deeper analyses provided later.

A strength of the chapters is their attention to Bellegambe’s sources, including for the Triptych of the Last Judgement of c. 1520‒25 (Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin). Bellegambe likely did not know the works by Dieric Bouts and Hieronymus Bosch to which passages of the triptych are sometimes compared. Koopstra instead convincingly demonstrates Bellegambe’s blending of motifs from printed sources. One instance of this practice appears in the triptych’s representation of Hell, aspects of which are derived from the illustrations in Le grand calendrier et compost des bergers (Calendar of the Shepherds), published in Paris in 1491. Another example, identified previously, is the derivation of the iconography of the Cellier Altarpiece of c. 1509‒11 (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) from the woodcut frontispiece of the Melliflui devotiq[ue] doctoris sancti Bernardi … opus preclaru[m], first published in Paris in 1508. It may be profitable to further investigate Bellegambe’s use of printed sources, since many single-leaf prints and printed books would have been available in Douai and via the monastic houses for which he painted. Patrons easily could have provided materials like this to the artist for consultation and direct representation, as Koopstra asserts.

A provision of this kind was likely behind the iconography of Bellegambe’s Cellier Altarpiece, which had its origins with the Cistercian convent of Flines outside Douai. Bellegambe painted a cache of works at the behest of this affluent community and its members during a period of reforms instituted in 1506, followed by the installation of a reform-minded abbess, Jeanne de Boubais (d. 1534), a year later. Jeanne’s coats-of-arms are featured in several paintings, likely pointing to her patronage, a practice of previous abbesses of Flines. The cited works with Jeanne’s arms are the Cellier Altarpiece, a leaf from a gradual, a two-volume antiphonary, and a devotional portrait diptych discussed below.[1] An antependium of the Lamentation (Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille) includes heraldry both for Jeanne and for Jacqueline de Lalaing (d. 1561), whom Jeanne appointed as her successor as abbess; I have argued that this dual representation suggests a tandem patronage project between the two women. Furthermore, other works apparently commissioned by the convent during Jeanne’s abbacy – some by Bellegambe – are described in a tally of the convent’s reform-related achievements. Archival sources credit these achievements to Guillaume de Bruxelles (or Bollart) (d. 1532), about whom Koopstra helpfully provides considerable biographical information. Guillaume was appointed as the nuns’ father confessor and assigned to provide oversight for the reforms at Flines.

Koopstra reinterprets the patronage situation at Flines through this hierarchical lens. We read that the Cellier Altarpiece was not, therefore, a commission of Jeanne de Boubais but rather of Guillaume de Bruxelles, despite the presence of her crest on the interior and a possible guised portrait, and thus it was he and not Jeanne who requested that Bellegambe adapt for the triptych the iconography of the frontispiece for the Melliflui devotiq[ue] doctoris sancti Bernardi. Koopstra does not accept Robert Genaille’s proposal that the figure of Bernard of Clairvaux’s sister Humbeline bears the features of Jeanne, for a new technical analysis reveals that the painter did not specify portrait-like physiognomy for the figure in the underdrawing. However, certain known portraits by Bellegambe, such as the Cistercian monk in the diptych mentioned below, are generalized. He painted very few portraits, which suggests that patrons did not find him to be an accomplished au vif painter. Similarly, the devotional portrait diptych portraying a Cistercian monk on the interior (earlier I argued that this figure represents Guillaume de Bruxelles) and Jeanne de Boubais with her heraldry on the exterior (Frick Art Museum, Pittsburgh) is presented here as his commission and not hers: the portrait of Jeanne, Koopstra argues, was added later by another artist, perhaps Bellegambe’s son Martin who also painted for Flines, at the request of Jeanne or nuns at the convent after her death, in her honor. The latter proposal may indeed be true, yet stylistic differences among the panels do not exclude Jeanne as the patron of the work as a whole.

This reevaluation of Jeanne de Boubais’s patronage activities is a sign that we are not yet past certain gendered assumptions about nuns. One is that the men who provided conventual oversight were the driving force of commissions in some convents. Another is that nuns who were active patrons were intellectually unsuited to develop content for their artworks. Jeanne de Boubais’s affluent pedigree, evident from her coat of arms, meant that she was educated; a letter written by her preserved in the Archives Municipales in Douai demonstrates her ability to read and write in French. Furthermore, the reforms at Flines encouraged lectio divino (“divine reading” of scripture and other edifying writings) by the nuns, activities that Jeanne surely modeled as their abbess. She absolutely could have known the printed book upon which the iconography of the Cellier Altarpiece is dependent just as readily as Guillaume, whom Koopstra argues requested the theme from Bellegambe. Jeanne also could have understood the iconography regardless of her ability to read the book’s Latin text, where the theme evidently is not identified (other than banderoles with the names of Bernard and his compatriot St. Malachy). Her choice of this woodcut for the Cellier Altarpiece could have been inspired by a desire to convey her knowledge of the order’s literature to the triptych’s beholders, a possibility that aligns with the imagery’s claims to achieving reform. Indeed, scholars have produced an impressive body of evidence that early modern nuns were astute strategists in using imagery to assert themselves with various audiences in and beyond their communities, even and perhaps most often when their independence and reputations were at stake.

Certain other conclusions by Koopstra also are more tenuous than they seem. One wonders, for example, if Bellegambe’s c. 1520 Triptych of the Trinity (Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille) was commissioned by the lay couple depicted on the right-hand wing, as Koopstra argues, or if they and Jacques Coene, abbot of the Benedictine abbey of Marchiennes, who appears with his shield on the left, commissioned it together – or by some other combination of patronage activities. Remaining receptive to hypotheses enriches our perspective, even as certain options seem more logical than others given available resources.[2] Scientific investigations can help in some cases, but they cannot resolve all problems like this. Furthermore, it is possible that residents of Douai and the surrounding monastic houses were particularly tradition-bound in their iconographic choices, embracing the familiar rather than asking for novelty. Perhaps we are too concerned with identifying innovation in works by Bellegambe (and other artists), which can obscure ways that patronage sustained rather than challenged norms. Either way, thanks to Anna Koopstra, we now have a useful, updated study of Bellegambe’s life, working methods, and approaches to iconographic sources upon which to build.

Andrea Pearson

American University, Washington, D.C.

========================================================================

[1] Bibliography on Flines can be found here: https://andreapearson.org/. It is possible that additional images with Jeanne’s arms have now been located.

[2] Suggestions for handling uncertainties like this in the context of gender appear in Andrea Pearson, “Gender, Sexuality, and the Future of Agency Studies in Northern Art, 1400‒1600,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 15, no. 2 (Summer 2023), forthcoming.