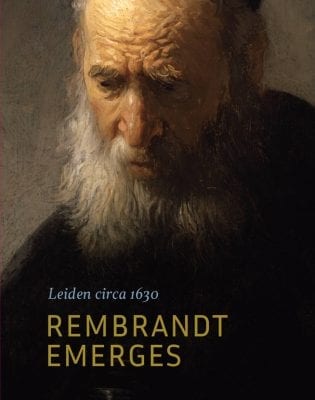

The Agnes Etherington Art Centre joined the celebrations of the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death (or immortality, if you will) with a traveling exhibition combining collection works and loans from the beginning of the master’s career. Curator Jacquelyn Coutré drew the Art Centre’s remarkable Head of an Old Man in a Cap into the spotlight, to tell the story of the artist’s breakthrough in his hometown of Leiden, when he came into his own, moving beyond his teachers, models, and peers. Another impulse for this choice comes from the collection’s strength in works by Jan Lievens, whose friendship with Rembrandt during these years was colored by a competitive spirit that spurred them both on to new heights. We furthermore benefit here from Coutré’s dissertation research on Lievens.

With its academic tone and international reach, the project gives a national stage for the study of Dutch Baroque Art at host at Queen’s University. A total of seventeen paintings, sixteen etchings and a single, impressive drawing is appearing in varying constellations at four venues. The year 1630 provides a window onto Rembrandt, for the Canadian public and for the international audience, much of which will only know the show as this reviewer does, through the substantial catalogue, in English, with a complete French translation at the back.

Jacquelyn Coutré solidly makes the case in a richly detailed lead essay, casting the period 1628–30 as one of becoming, and Leiden as the city where Rembrandt took his first steps on his own. It is after all the context in which Rembrandt (with Lievens) launched the “tronie,” studied emotions, took on his first pupils, and engaged the attention of Constantijn Huygens with small-figured history paintings, such as the Judas Repentant (Mulgrave Castle, Lythe, North Yorkshire). Coutré astutely draws attention to Rembrandt’s monogram, the last letter of which refers to Leiden, and channels the fame of Lucas van Leyden. She also affirms the importance of the city’s scholarly context, a point previously highlighted in the Art Centre’s 1996 exhibition Wisdom, Knowledge & Magic. New evidence that Rembrandt matriculated for a second time at the University, thereby extending his contact with the scholarly world, surfaced too late for this publication (Jef Schaeps and Mart van Dijn, Rembrandt en de Universiteit Leiden, Leiden, 2019). But then, the unacademic Lievens also celebrated Leiden bookishness.

The period leading up to 1630 also saw Rembrandt establish himself as a printmaker. Rembrandt scholar Stephanie Dickey, Professor of Art History at Queen’s University (and past president of HNA), sets this moment in the context of Rembrandt’s friendship with Jan Lievens and his collaboration with Jan Gillisz. van Vliet. Of course, the role of Van Vliet remains puzzling, as Dickey points out: he may have provided the facilities and assistance with making etchings, even as he reproduced Rembrandt’s paintings in print. Etching played a core role in experimentation and innovation for both Lievens and Rembrandt, as Dickey demonstrates with a discussion of their printed tronies. The high point of their competitive exchange, their depictions of The Raising of Lazarus, entailed prints as well as paintings, with Lievens reproducing his own invention closely, but Rembrandt not able to resist introducing changes in the translations to print.

An extended contribution by archival art historian Piet Bakker offers new insights into the specific character of the city of Leiden, a promise set out in the title. He focuses on the fact that there was no painter’s guild in the city as Rembrandt was emerging as an artist, despite several attempts to establish one. Markets often featured imported paintings. Bakker draws an illuminating connection to the ambition of Rembrandt, Lievens, and even Dou. All three quickly gained patronage at an elite level that would have rendered superfluous a guild, which traditionally protected a local market for artists at a more popular level of regular production. With Huygens and his circle in the picture already by 1628, Rembrandt and Lievens leapfrogged the local market early, and were soon ready to move on to bigger things.

The essay section closes with a new contribution to the history of Rembrandt reception: the Canadian context. Collecting history specialist (and past director of the Agnes Etherington Art Centre) Janet Brooke chronicles the unsteady growth of the master’s presence in private and public collections. The 1909 Hudson-Fulton exhibition in New York sparked interest north of the border, but two early Rembrandt acquisitions in Montreal, by businessman-engineer James Ross and Knickerbocker railway magnate Sir William van Horne, left for American collections and museums. The examples that stayed, in Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa, formed part of broad, encyclopedic collections, following American models, the so-called “museums of the future.” The most recent acquisitions, four paintings in the Bader Collection at the Agnes Etherington Art Centre, provide a striking contrast. They reflect a focus on the artist and his circle of pupils, friends and followers, of a single collector, Alfred Bader, who engaged closely with new research initiatives, and concordantly supported scholarship in this field as well.

The extended catalogue entries further flesh out the theme of artistic emergence around 1630. With the Self Portrait from the Snite Museum visitors are treated to an impressive example of this important category in Rembrandt’s work, only recently rehabilitated. Another brilliant loan is Joudreville’s Minerva from Denver, a complete gloss of his instruction under Rembrandt, which also does not hide the distinctive quirks he cultivated, and his teacher evidently did not rectify. Fortunately, great care is taken with the attribution of the challenging Tribute Money in Ottawa. I would add that its extensive quotations of Rembrandt’s work characterize the approach of a devoted pupil in the studio, in stark contrast to the celebrated Judas, with its many creative leaps traced in drawn studies. The tiny Scholar by Candlelight (which opened Amsterdam’s historic Rembrandt exhibition of 1898) is likely also the work of a pupil demonstrating a full range of effects, but in an unresolved composition. These works and this exhibition vitally confirm the tremendous excitement in Leiden accompanying the emergence not only of two young masters, but also of a new path for art in the young Republic.

David de Witt

Museum Het Rembrandthuis