Insects have been enjoying increased visibility in early modern art history studies. After the late Janice Neri’s book, The Insect and the Image: Visualizing Nature in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1700 (Minneapolis, 2011), Marisa Bass authored a Bainton Prize-winning volume, Insect Artifice: Nature and Art in the Dutch Revolt (Princeton, 2019). Both build upon Susan Dackerman’s seminal exhibition, Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge-Evanston, 2012), which presented the wider, interdisciplinary context of visual description within natural philosophy. Bass also stressed the effects of political ferment in the Netherlands during the early years of the Dutch Revolt, led by the work of miniaturist Joris Hoefnagel (1542-1600), in a complement to a massive scholarly catalogue of his work by Thea Vignau-Wilberg.[1]

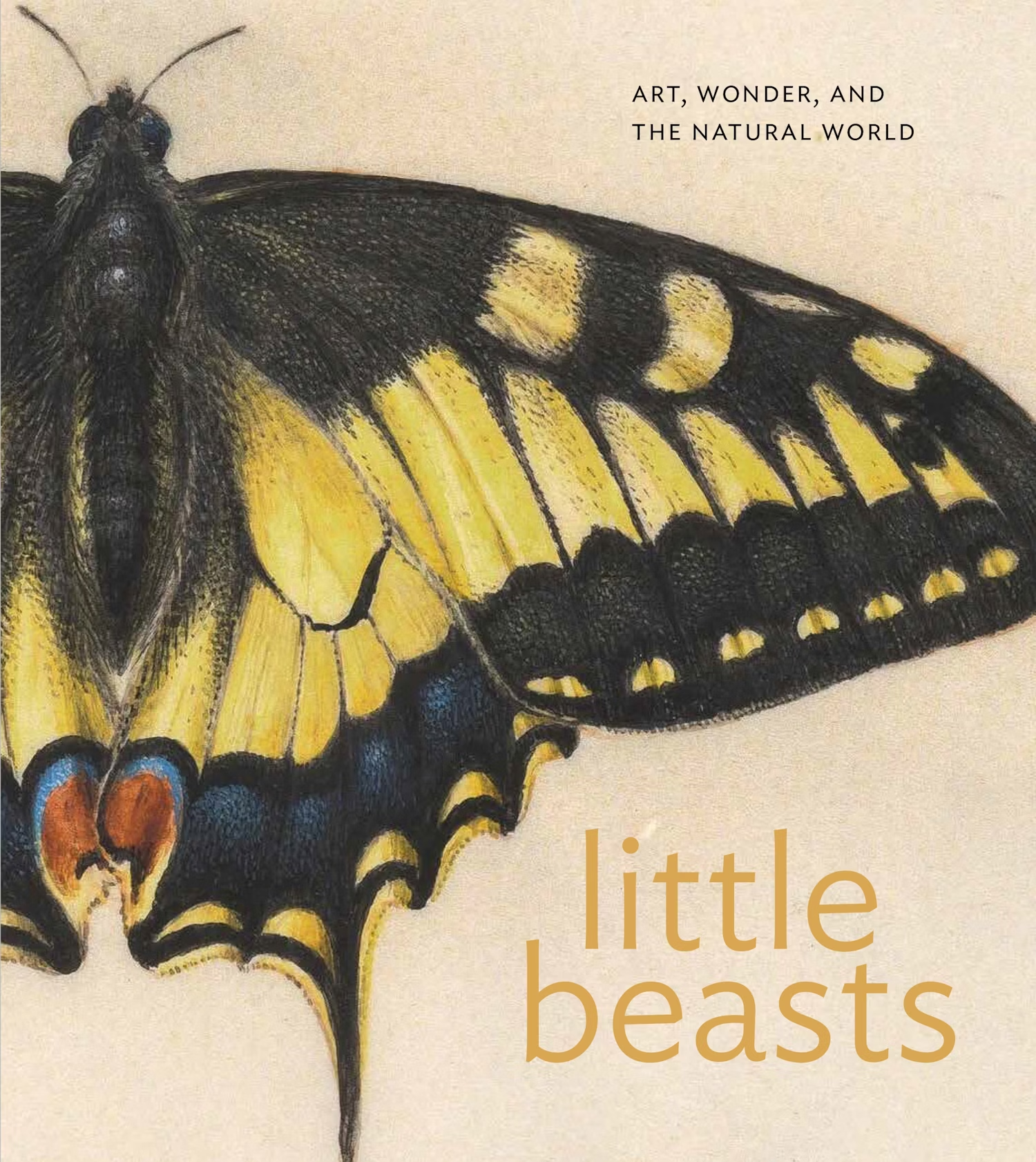

Since the National Gallery in Washington holds Hoefnagel’s exquisite Four Elements illuminations (300 of them), those volumes form the starting-point for this splendid new exhibition, multum in parvo, small fauna depicted at small scale and accompanied by epigrams like early emblems. Rather than producing a conventional catalogue, however, here the authors, all National Gallery curators, have compiled a book of stimulating essays about several prominent practitioners of small nature imagery. Hoefnagel is featured, of course, bookended by Jan van Kessel from the following century. In effect, this is a focus show, with the objects on view chiefly drawn from the National Gallery collections, supplemented with actual specimens from the nearby Smithsonian Natural History Museum. The media on view range from illuminated miniatures to panel paintings and graphic works – all addressed to a collectors’ market, including elite princely collections (Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II probably once owned the Hoefnagel volumes). Together, these images emphasize a pictorial merger between Kunst and Wunder. Additionally, in the Gallery installation, Until We Are Forged: Hymns for the Elements, a poetic and wistful film by Dario Robleto, commissioned to accompany the exhibition, offers a contemporary take on these earlier images and their conservation for future generations.

Noted historian of science Brian Ogilvie (The Science of Describing: Natural History in Renaissance Europe, Chicago, 2006) opens the volume with a learned guest essay (“Natural History in the European Renaissance”). He underscores connections between visual imagery and the emerging body of observational science at the turn of the seventeenth century, but the actual science of classification would only emerge in the next century. He mentions the first natural history book devoted to insects, Thomas Moffett’s Latin Theater of Insects, or Lesser Living Creatures (ca. 1590; first published in 1634). That work asserted the Book of Nature as the sign of the Creator, while also claiming that nature was created in order to serve humanity.[2] Ogilvie also traces collecting animals as naturalia in curiosity cabinets, Wunderkammer, as well as menageries along with “paper museums,” such as the collected images of, Ulisse Aldrovandi, Cassiano dal Pozzo, or the printed zoology of Conrad Gessner.[3] Among later images is the microscope etching, Flea (1665), recording the observations of Robert Hooke.

Stacey Sell tackles the magnificent Hoefnagel series (“’Through Such Variety, Nature is Beautiful’: Joris Hoefnagel, The Four Elements, and Natural History”), noting how the volumes’ imagery interacts with current knowledge about the natural world, including published zoology compendia, chiefly Conrad Gessner, whose woodcut illustrations served as one major visual source. Here the pioneering analysis of the Four Elements by Lee Hendrix should be mentioned. But Hoefnagel, a court artist in Bavaria who was not a naturalist, also includes erudite emblematic phrasing for his imagery and combines multiple animals on many pages. In many miniatures he adds shadows below the creatures and places them within landscape settings. Sell is particularly attentive to the meticulous technique of Hoefnagel, who used actual insect wings in several images. He thus bestrides the contrasting categories of naturalia and artificialia, also bridged by elaborate goldsmith settings for acquired shells or horns in a contemporary Wunderkammer.

While the Four Elements remained an exclusive preserve of its princely owners, Hoefnagel’s son Jacob (1573-1632/33) produced a 1592 series of 48 engravings after his father’s designs, the Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnageli, with clustered insects and plants, seemingly strewn across the paper surface and captioned with epigrams to form meditational emblems on primal spiritual issues, such as the brevity of life and the wonders of Creation.[4] That family legacy is the province of Brooks Rich (“Survival of the Finest: Animals in Early Modern Intaglio Print Series”). He traces other subsequent print series, chiefly detailed Netherlandish intaglios (especially issued by Adriaen Collaert in the 1590s), inspired by, or continuing the influence of Hoefnagel. Such projects continued into the seventeenth century, culminating with etched insects (1646) and shells by Wenceslaus Hollar in England that ensured both further distribution of both observation and knowledge.[5]

In the final essay Alexandra Libby (“”Monstrous Creatures and Deverse Strange Things’: The Art of Jan van Kessel”) links Van Kessel to the great era of naturalia collecting during a period of trade and colonial expansion across the globe. His works’ use of prior visual models combined with direct observation in a culmination of the trends previously presented. Yet with humor, several of Van Kessel’s small-scale images also feature playful signatures formed by caterpillars or snakes. A great-grandson (via his mother) of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Van Kessel shared the fascination with the natural world of his uncle Jan Brueghel the Younger as well as his own namesake father Jan the Elder. One large set of carefully wrought miniatures on show from nearby Oak Spring Garden Foundation features fine brushwork in gold; together these panels simulate the painted surfaces of drawers on actual cabinets of curiosity in contemporary collections.

In addition to its value for these scholarly essays and their references, this truly beautiful book, lovingly produced with marginalia and full-page illustrations as well as vivid details, is a credit to Princeton University Press. Even its gilded edges show insects in raking light. However, it is not a true catalogue of works on view, but rather a set of complementary essays elucidating those objects in roughly the same order as the installation. Some of the essay’s narratives emerge in the galleries with visual comparisons and notes on epigrams and inscriptions, made accessible through touch screens across the exhibition. Thus, to experience this remarkable exhibition itself, one requires an on-site Washington visit. A long run lasts until 2 November. Visitors to Washington DC should also be aware that a complementary exhibition about insects in natural history books is mounted at the National Museum of Natural History as Dazzling Diversity (until December 16, 2025). And as a further complement to the main exhibition, the National Gallery Library assembled a display of forty illustrated rare books with the theme, “Animal Illustration in Europe, 1550-1750.” Most of those volumes postdate the items in the exhibition, but some show varied kinds of contemporary publications featuring animal observations that would also have graced collections.

One result of the intensive conservation effort behind this exhibition is the display of brushes and pigments used by Hoefnagel, but also the extraordinary process, called lipidochromy, where the artist used adhesive to capture actual scales of butterfly wings in his images. Another display underscores his use of shiny metallic pigments to provide iridescence for surfaces of insect carapaces when pages of the manuscripts were turned.

Besides the four incomparable Hoefnagel volumes, other works featured on the walls include a roomful of works by Jan van Kessel, including his image after Jan Bruegel of Noah assembling the animals for the ark (Baltimore, Walters). Remarkably, the National Museum of Natural History’s entomology department assembled a tableau of naturalia expressly for the exhibition, which imitates Van Kessel’s work with actual specimens beside the artwork. Works on paper from the Gallery’s collection also play a major role, led by Hans Hoffmann’s Red Squirrel in the manner of Dürer (1578), Ligozzi’s groundhog (1605), and several Hollar engravings of insect varieties – all complemented by individual specimens from the collection of the Natural History Museum. Print series by Jacob Hoefnagel and Adriaen Collaert show how widely dispersed these images about these varied creatures were, both as principal subjects and as marginal ornament.

To peruse the fascinating pages of this publication (including works not on view) and to inspect the objects themselves in the galleries surely sharpens one’s vision, provokes still further curiosity, and ultimately provides valuable lessons in both art history aiding natural history at its origins. Viewers will want to inspect these small works of small creatures as closely as the artists once did.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania, emeritus

[1] Thea Vignau-Wilberg, Joris and Jacob Hoefnagel: Art and Science around 1600 (Berlin, 2017).

[2] Eric Jorink, Reading the Book of Nature in the Dutch Golden Age 1575-1715 (Leiden, 2010).

[3] General: Florike Egmond, Eye for Detail: Images of Plants and Animals in Art and Science, 1500-1630 (London, 2017). For Aldrovandi, Neri, Insect and Image; also, Peter Mason, Ulisse Aldrovandi: Naturalist and Collector (London, 2023). for Cassiano: Henrietta McBurney, Ian Rolfe, et al. eds. Birds, Other Animals and Natural Curiosities (London, 2017); for Gessner: Urs Leu, Conrad Gessner (1516-1565): Universal Scholar and Natural Scientist of the Renaissance (Leiden, 2023); Ann Blair, “Humanism and Printing in the Work of Conrad Gessner,” Renaissance Quarterly 70 (2016), 1-43.

[4] For Jacob Hoefnagel, Vignau-Wilberg, Joris and Jacob Hoefnagel, 461-519, and her facsimile of the Archetypa with translations (Munich, 1994).

[5] For shells, Marisa Bass et al., Conchophilia: Shells, Art, and Curiosity in Early Modern Europe (Princeton, 2021).