Tatjana Bartsch’s book on Maarten van Heemskerck (1498–1574, in Rome 1532–c. 1537) delivers the most thorough analysis to date of the artist’s extant corpus of Roman drawings. As renowned as is Heemskerck’s Roman phase, as familiar as we are with many of the 100-plus drawings that the Haarlem artist executed while in the Eternal City, these topics have only recently attracted sustained scholarly attention. Heemskerck and his sixteenth-century Netherlandish counterparts who went to Italy returned to the Low Countries to make art in a style that we have been slow to associate with the Netherlands. Featuring neither the shimmering surfaces of Van Eyck nor the combination of caricature, fantasy, and genre earthiness of the Bosch-Bruegel line, Netherlandish antiquarian art bears a lexicon of motifs after the antique (all’antica): muscular nudes, flowing drapery, pediments, columns, and a veritable lost civilization of ruins.

Post-war scholarship has gradually augmented the bibliography about Netherlandish antiquarianism. Surveys of Netherlanders in Italy, seminally by Nicole Dacos (1966, 1995, 2004) and most recently by Maria Harnack (2018), have organized thinking around the phenomenon’s broader issues. Monographic studies, too, notably Maryan Ainsworth’s Jan Gossart catalogue (2010) plus Michiel Coxcie by Koenraad Jonckheere (2013), Gossart by Marisa Bass (2016), and Floris by Ed Wouk (2018), have interwoven those artists more thoroughly into Netherlandish art history.

But out of all Netherlanders working in an antique manner, Heemskerck has enjoyed the most scholarly attention, however sporadic. Milestones include Christian Hülsen and Hermann Egger’s annotated facsimiles of two bound drawings volumes in Berlin, and Ilja Veldman’s 1977 book on the artist’s collaborations with Netherlandish humanists remains crucial. Catalogues of his paintings by Rainald Grosshans and Jefferson Harrison, appearing in the 1980s, were complemented by Veldman’s compilation of Heemskerck’s 500-plus extant prints in two New Hollstein volumes (1994). In the 2010s Bartsch and Peter Seiler co-edited a 2012 anthology of essays on Heemskerck’s drawings, and Bartsch has published several articles on Heemskerck. My own study of Heemskerck’s ruinscapes (2019) and the volume under review here appeared in the same year.

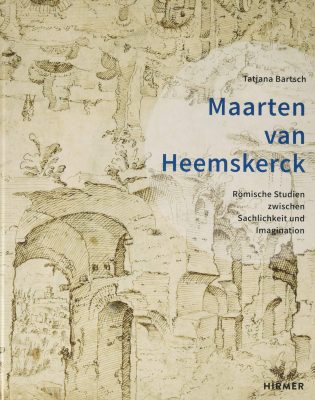

Building on her dissertation, Bartsch’s book culminates her nearly two-decade study of the artist’s Roman stay. Its subtitle, “between objectivity and imagination,” suggests that Heemskerck’s Roman drawings are neither pure documents of their subjects nor caprices. Rather, they provide the fountainhead for his inventions all’antica. His vedute, especially, sometimes take liberties with their sites, heralding his inventive ruinscapes in many post-Roman works in all media.

Over seven chapters, Bartsch takes readers from Heemskerck’s Haarlem origins to his Roman sojourn. She then assesses the function and fate of his Roman oeuvre. Much here builds on earlier scholarship. For example, Bartsch repeats that Heemskerck’s time assisting Jan van Scorel provided him with a model for drawing Rome’s antiquities. She adds to the discussion by bringing in a stunning chalk drawing of the Palatine’s ruins, emanating from Scorel’s circle, if not from the master himself. Bartsch also reprises Dacos’s elaboration of Polidoro da Caravaggio’s importance for Heemskerck, though with minimal citation. She reinforces the discussion by Kathleen Christian about Heemskerck’s Roman network as well as my own connection between Heemskerck’s drawings and notions of memory. Thus, Bartsch’s insights often build on and reinforce inherited scholarship, though her citations remain token.

Fortunately, she also furnishes fresh insights about Heemskerck. Bartsch suggests that the smaller drawings, originally bound and popularly called “Heemskerck’s sketchbook,” did not really comprise a sketchbook. Noting the high finish of many of its drawings, Bartsch labels it more accurately as a Zeichnungsbuch. This seemingly small perceptual shift suggests substantial considerations concerning function. Heemskerck apparently conceived his booklet for an audience of potential collaborators – artists, patrons, and publishers – who would have appreciated its portable collection of antiquities and motifs for later use in prints and paintings all’antica.

But Bartsch’s most significant contribution comes from her meticulous archival explorations. Her final chapter plots the afterlife of the Roman drawings. After they left Cornelis van Haarlem’s possession upon his death in 1638, Bartsch has traced their ownership from van Haarlem to Pieter Saenredam, Jan de Bisschop, Comte de Caylus, and the Mariette dynasty. This research results in another strength of the book: its demonstration of the 17th-century interest in Heemskerck, which now appears more crucial for Dutch classicism than previously suspected.

The catalogue that follows, comprising a full two-thirds of the book, gives the most extensive documentation of Heemskerck’s Roman oeuvre since Hülsen and Egger. It is also the first to bring all of Heemskerck’s Berlin drawings together with all other known sheets associated with him. The catalogue sequence presents the Zeichnungsbuch, followed by loose sheets drawn in Rome, Heemskerck’s Roman paintings, copies after Heemskerck’s known Roman drawings, and copies after his unknown Roman drawings. Unfortunately, Bartsch’s catalogue missed an opportunity to help solve a persistent problem of attribution in Heemskerck-studies, particularly for newly discovered drawings of Rome executed in the pen-and-ink hatching technique so often, and arbitrarily, associated with Netherlanders. Indeed, the designation, “copies after unknown Heemskerck drawing,” is appropriate for the so-called de Vos sketchbook, with its multiple drawings per sheet, many of which copy Heemskerck’s known drawings alongside other motifs. However, it also encourages the persistent notion that any sixteenth-century pen-and-ink hatched drawing of Rome must somehow be traceable to his hand. Even within his prolifigate production and impressive technical range – from the lion’s claw to high finish in chalk, pen-and-ink hatches, and ink wash – it is unlikely that all drawings attributed to him are truly his. Examining the current corpus of “autograph” Heemskercks reveals some fundamentally different techniques, suggesting that “circle of” or “copy after” designations are more appropriate, pace Bartsch. Bartsch’s catalogue thus further confuses an already confused situation, while providing scant explanation wherever she has changed attribution. As the scholar who has spent the most time studying the physical characteristics of all extant drawings associated with Heemskerck’s name, she could have done much more to sort out their attribution problems.

Problems aside, this book’s strengths are many. It is the most complete source on Heemskerck’s Roman oeuvre. It presents most of the major ideas on the subject, while offering judicious, important new ones. Moreover, Bartsch’s detailed understanding of Rome’s building histories will enable architectural historians to make even more effective use of Heemskerck’s vedute. Hirmer’s high production values present all drawings and almost all comparative works in color and legible large scale. Still lacking are studies that synthetically approach Heemskerck’s drawings, paintings, prints and his place within Netherlandish art history. Bartsch has provided one foundational source for such future works.

Arthur J. DiFuria

Savannah College of Art and Design