Ronda Kasl’s text is an indispensable addition to the literature on Isabelline art, an area often on the periphery of current art historical scholarship of the fifteenth century. Kasl addresses this gap in the literature first by bringing close attention to a number of essential Hispano-Flemish works, predominantly sculptural funerary monuments. The phrase “Hispano-Flemish”, a problematic and imprecise stylistic term coined by Elías Tormo in the early twentieth century, is used to describe the hybridized visual tradition that combined Flemish artistic innovation with the localized traditions of the various Iberian kingdoms, resulting in artworks that are neither quintessentially Netherlandish nor Spanish. Kasl situates this hybrid style within its cultural context by also considering “whether there is any relationship between the reception of the new [Northern European] style and its capacity to assert emerging social, political, and spiritual values and aspirations” (1).

Kasl answers this complicated question in two parts. In the first she gives a detailed overview of the construction of the Hispano-Flemish style by both hispanized Netherlandish immigrant artists and by Spanish artists incorporating Northern European aesthetics into their practice. Kasl nuances the cultural context by relating the artworks created in Castile to the socio-political and economic networks between Spain and the Low Countries. The second part focuses on the Royal Monastery of Miraflores and the ability of the Hispano-Flemish style to communicate the specific monarchic ideology of Queen Isabel I.

In chapter 1, Kasl does an excellent job of combining the extensive literature on the exporting of art from the Netherlands with collecting practices in Iberia in order to establish the demand for and use of Flemish and Hispano-Flemish artworks. The text explores the myriad of ways that the Netherlandish style became known in Iberia, including the direct commissioning of artworks in the Low Countries by Spanish patrons for display in an Iberian context, the importing of works to be sold on the open market, and the movement of Northern European artists to the Iberian Peninsula. The analysis is heavily based on close attention to documentary evidence, where available, and astute supposition where it is not.

Examination of the material evidence of specific objects, such as the works associated with Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca, bishop of Badajoz, Cordoba, Palencia, and Burgos, provides further evidence of the variety of means by which Iberians acquired Netherlandish styled artworks. Fonseca was sent to Flanders on at least three occasions between 1499 and 1504. While in the Low Countries, Fonseca acquired tapestries, paintings, and possibly an illuminated book of hours. Two tapestry sets with Fonseca’s heraldry survive in the Cathedral of Palencia, one with the coat of arms woven into the original border indicating a direct commission and one where the heraldry was added onto an already finished tapestry, suggesting purchase on the open market. Fonseca also commissioned works by Flemish artists working in Castile for the high altarpiece of the cathedral of Palencia.

Kasl then shifts attention to the specific use of the Hispano-Flemish style by non-royal courtiers in their funerary chapels. The text takes a close look at several individual projects, created predominately by immigrant Northern European artists, within the context of the patrons’ political and familial networks. The resulting study, chapter 2, provides a careful interpretation as to how these nobles used their funerary spaces to communicate their position vis-à-vis the monarchy. Although the chapter considers sites across Castile, many of the monuments come specifically from Burgos and the surrounding region, providing an essential context for the study of Miraflores in the second part of the text.

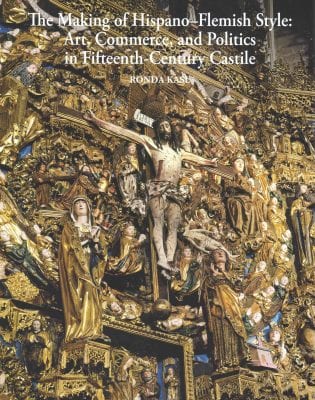

Chapters 3 and 4 consider Queen Isabel’s patronage at Miraflores. Initially a hunting lodge, the structure had begun to be converted into a Carthusian monastery and royal burial site by her father, Juan II, in accordance with his father’s wishes. A devastating fire followed by the tumultuous reigns of Juan II and Enrique IV caused the project to largely fall under Isabel’s purview. Kasl focuses primarily on the works created by Gil de Siloe: the Tomb of the Infante Alfonso (1486-92), the Tomb of Juan II and Isabel de Portugal (1486-93), and the Altarpiece of the Trinity (1469-99). She situates these specific commissions within the larger decorative program that included additional sculptures, stained glass, and panel paintings. The artworks are also interpreted through the history of funerals and court rituals at the site.

By meticulously analyzing the condition and alterations of the remaining sculptures of the Tomb of Juan II and Isabel de Portugal, Kasl is able to present a convincing conceptual reconstruction of the original sculptural elements based on the size, shape, and condition of individual components. She then interprets the cumulative iconography in both funerary and dynastic contexts in order to “confirm Trastámara legitimacy and to assert the precedence of the Castilian monarchy” (149). The analysis is supported by well-chosen passages from a variety of devotional and political textual sources in addition to the careful consideration of the monument. Kasl argues quite successfully that Isabel’s decision to commission the work, along with the overall Miraflores program, in the Hispano-Flemish style was due at least in part to the use of this aesthetic by the noble families of Burgos to convey their own ascendant social position, and that her adoption of this local tradition enhanced the communication of her own ideological message.

Kasl’s methodically researched and carefully articulated text is a refreshing counter to the prevailing historiographic narrative of the Hispano-Flemish style, which has largely focused on the problem of parsing out works by Spanish imitators from hispanized Flemish immigrants. The appearance of a methodologically important English language text will, hopefully, support a growing interest in Hispano-Flemish art among those interested in the complex reception of Netherlandish art in the wider European context.

Jessica Weiss

Metropolitan State University of Denver