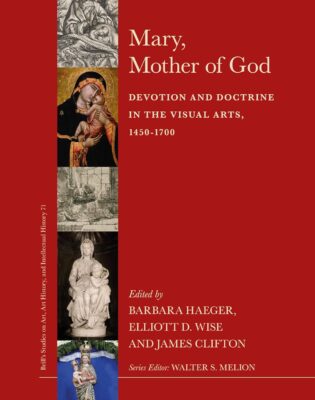

Numerous books survey with images the history of concepts about the Virgin Mary.[1] Yet the editors of this probing new volume have addressed both Marian theology as a source for visual topics in unprecedented depth, with a focus on early modern European art. Ten essays analyze case studies from both Italy and Northern Europe but also New Spain and Mughal India, which show the global expanse of Catholic art.

A brief Introduction sets the stage with the biblical accounts of Mary and her central role in the Incarnation of Jesus in human form. Her maternity and her emotional vicissitudes, recorded in both joys and sorrows (as Mater dolorosa) formed powerful models for pious Christians across the target period, 1450-1700. As the mother of Jesus, Mary was also understood as intervening on their behalf with her mercy as Maria mediatrix at the moment of divine judgment.

The first three essays, richly researched with excellent bibliographies, examine Marian devotion in the North, France and the Netherlands. Elliot Wise focuses on the 1452 cult image at Cambrai, Our Lady of Grace, based on a tender Byzantine Eleousa icon type ascribed to the hand of Saint Luke. He notes that it embodied divine purity, grace, and divinity of Jesus in the arms of his mother. Soon widely copied by leading Netherlandish artists, not least for its Lucan pedigree, variants include the venerated Mariahilf image (ca. 1525; Innsbruck, St. Jakob’s church) by Lucas Cranach (another Luke), a later cult image widely copied in its own right. Wise notes the Cambrai painting’s counterpoint with a rival Mary image, a miraculous, if crude, “tree Madonna” at Scheut.[2]

The next article by Anna Dlabacová revisits major meditational sequences that arose in the late fifteenth century: the practice of the rosary as well as the Five Wounds of Christ and the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin. She points to the powerful stimulus provided by Gerard Leeu, an early printer of incunabula, who specifically illustrated prayers in both Latin and the vernacular for these devotions. A major puzzle piece of Netherlandish devotional history emerges from her research.

James Clifton analyzes the link between flowers and fecundity in Marian symbolism. Drawn ultimately from the Song of Songs, where the bridegroom is identified with Christ and the bride with Mary, divine love and flower imagery become inextricable, already in fifteenth-century visuals, though Clifton focuses on later sixteenth-century engravings by Adriaen Collaert, the Wierixes, and others.[3] More specifically, using Mariological texts as evidence, Clifton subtly links imagery of a carpeted bed of flowers as a simulacrum for the womb of the Virgin and the garden of the soul.

A pair of studies link material with maternity, Mary as mater. Kim Butler Wingfield connects Michelangelo to Franciscan piety (rather than the more usual Dominican theology of Savonarola), centered at Santa Croce in Florence, where the artist was buried. She claims that fleshly strength and marble material conjoin in Michelangelo’s imagery of the Virgin: from his early Madonna of the Steps, Pietà, Doni Tondo painting and Bruges Madonna to his later Pietà drawing for Vittoria Colonna, featuring Mary’s corporeality and her role in the Incarnation, especially during her com-Passio for the humanity of her suffering son. Her fresh rethinking reinvigorates both viewing and interpreting Michelangelo’s religiosity.

Barbara Baert theorizes about images that represent the divine itself, making the invisible manifest. Focusing on the Annunciation and its implications for the Incarnation, she conceptualizes sensual aspects of “interspace” as text transforms into visuality and of the “self-aware image,” as coined by Victor Stoichita.[4] But she also points to the mystery of “now-time,” at once a specific event but also a “pregnant” moment (almost in the terms of Lessing’s Laocoön, though she does not invoke that work). Both text and idea take form in her chosen Quattrocento images of the Annunciation. The key figure is an angel, but its word, the Annunciation itself, is divine speech, sometimes inscribed on paint surfaces (Fra Angelico) or represented in golden rays (Gentile da Fabriano) or the dove of the Holy Spirit, aimed toward its silent recipient, Mary. Baert also ties the familiar figure of the angel to a most appropriate ancestry: winged Greek god, Kairos, embodiment of the right moment, here the crucial instant of transition.[5]

Another trio of studies address the contested image of Mary during the Counter Reformation era. Steven Ostrow considers the Jesuit theology behind Gaulli’s great ceiling painting of heaven at the central dome in their mother church, the Gesú. There the Virgin appears with the tripartite Trinity and saints, offering her maternal breast in a “double intercession” with Christ and his wounds on behalf of sinful humanity before God the Father at the Last Judgment. The entire dome thus offers a post-Tridentine riposte to Protestant challenges to the Virgin’s role as intercessor along with saints, but it draws on earlier theology and visual precedents, including works from Northern Europe.

Barbara Haeger complements Ostrow’s Jesuit-centered discussion with Van Dyck’s own assertion in his Lamentation (ca. 1635; Antwerp Royal Museum) of Mary’s role in human salvation. Here Mary’s com-Passion with outstretched arms indicates her role on the original site of the altar, dedicated to her Seven Sorrows in the Antwerp Church of the Recollects (the same devotion discussed above by Anna Dlabacová). In its original site, Mary’s painted suffering was paired with a standing statue of her, a Stabat mater beneath the cross, while pierced by the sword of the Seven Sorrows (Luke 2: 35). Haeger proposes that Mary’s suffering and her cooperation with the divine plan of her son’s sacrifice on the cross reinforces her contribution as a co-redeemer.

Farther afield, in the Calvinist Dutch Republic, Shelley Perlove discusses how Rembrandt departed from his contemporaries in depicting images of the Holy Family. These ostensibly Catholic subjects, several of them based on Italian models from prints (e.g. Mantegna), accommodate Protestant cavils by omitting more cultic elements, as they strive for a more universal Christian imagery. Like other authors in the volume, Perlove examines Mary’s role in Passion imagery as well as the Presentation in the Temple (where Simeon prophesies her sword of sorrows) as well as a Holy Family etching (1654), a subject appropriate for Protestants and Catholics alike. A mature, sorrowful Mary even takes center stage in a late etching (1652) of the Virgin with Instruments of the Passion, but she no longer embodies the standard ideals of power and physicality of Michelangelo.

When Catholic missionaries evangelized in New Spain, shrines to Mary sprang up across Mexico. Cristina Cruz González focuses on a miracle-working Franciscan cult statue in polychromed alabaster, Our Lady of Tepepan. She stands upon a supporting Atlantean figure of St. Francis himself, largely based on an allegorical Rubens oil sketch devoted to the Franciscan doctrine of Immaculate Conception (1631-32; Philadelphia Museum), which circulated as a print, well studied recently by Aaron Hyman (not cited).[6] Cruz González focuses on the Flemish friar, Pedro de Gante, who established the cult as well as the local veneration of the pure white material itself, a vestige of pre-Christian Aztec worship.

The final study by Mehreen Chida-Razvi turns to Mughal India, whose emperors, particularly Jahangir (r. 1605-27) adopted Christian forms for their own glorification with such formal attributes as haloes and angels. Chida-Razi focuses on wall paintings of the Virgin on the walls of the emperor’s buildings, including throne rooms of his palaces in Agra and Lahore. She points out the presence of Mary in Muslim theology – the only woman named in the Qur’an, Maryam. Based on circulating prints of Jesuit missionaries, the best documentation for these lost works is the careful visual recording of ceremonies in Mughal manuscripts. Her association with public audiences as a complement/compliment to imperial power, reinforcing dynastic legitimacy and authority with an aura of divinity.

Taken together, this volume makes an important contribution to knowledge about its familiar subject. By focusing on particular artists and works, a group of accomplished scholars, many of them senior, has adduced richly researched theological interpretations of Marian imagery. Many aspects of Mariology converge across these studies, including her own specific devotions, such as the Seven Sorrows, as well as her importance as co-redemptor in salvation, marked especially by her co-suffering participation in events of the Passion. Symbolic attributes, such as flowers, and the aura of Marian images themselves add rich layers to our understanding of early modern Catholic piety in this valuable book.

Larry Silver

University of Pennsylvania

[1] Among the more authoritative yet approachable volumes: Miri Rubin, Mother of God: A History of the Virgin Mary (New Haven, 2009); Jaroslav Pelikan, Mary through the Centuries: Her Place in the History of Culture (New Haven, 1996).

[2] Discussed by Craig Harline, Miracles at the Jesus Oak: Histories of the Supernatural in Reformation Europe (New York, 2003), esp. 11-51. The newly founded Carthusian monastery at Scheut, near Brussels, also housed Rogier van der Weyden’s austere, large Crucifixion.

[3] For the earlier imagery of symbolic flowers and fruit, Reindert Falkenburg, The Fruit of Devotion: Mysticism and the Imagery of Love in Flemish Images of the Virgin and Child, 1450-1550 (Amsterdam, 1994). See also Lieve Watteeuw and Hannah Iterbeke, eds., Enclosed Gardens of Mechelen. Late Medieval Paradise Gardens Revealed (Amsterdam, 2018), a study of meticulous multi-media constructions by nuns of paradise gardens with the Virgin and female saints.

[4] Victor Stoichita, The Self-Aware Image: An Insight into Early Modern Meta-Painting, rev. ed. (Turnhout, 2015).

[5] Barbara Baert, Kairos or Occasion as Paradigm in the Visual Medium (Louvain, 2016), spells out the visual tradition of this deity, summarized in her article.

[6] Aaron Hyman, Rubens in Repeat. The Logic of the Copy in Colonial Latin America (Los Angeles, 2021), 216-256.